One of the most profound insights emerging over the last few decades is the insight that humans live on a planet where humanity is no longer a minor player in a vast planet with vast oceans, a vast atmosphere, and vast forests. Instead, we’ve begun to understand that humanity is a significant agent in transforming that planet's basic nature and changing its atmosphere, ocean, and biosphere. This transformation in thought is occurring in many different ways. It isn't just about climate change. It isn't just about biodiversity loss. It isn't just about plastics and waste in the oceans. All of these things are considered together.

The word "Anthropocene" has emerged over the last few decades to name this way of thinking. This word comes from the geological time scale, where there are aeons and periods and epochs. Moreover, by using this geological time scale, what “Anthropocene” implies is that we've moved into a new geological epoch. We've left the epoch in which all of human history has occurred, the Holocene, which began around 10,000 years ago. Before the Holocene, there was the last major ice age, and the Holocene signalled a period of climate stability for approximately 10,000 years. During that period of climate stability, all of human civilisation occurred.

What the Anthropocene proposes is that the Holocene is over. We've now moved into a new world where the climate is entering a period of instability. Many aspects of the earth are changing so profoundly that it's likely to leave a geological record in the sediments of history. For example, if a future geologist came from another planet to Earth in a hundred million years, they would see clear signals in the geological record marking the Anthropocene's start.

So, in some ways, “Anthropocene” is a geological term, but it's much more profound than that. The term is trying to offer us a mindset that recognises the world is finite, and that we live as a large entity on this finite planet.

Understanding our world is finite

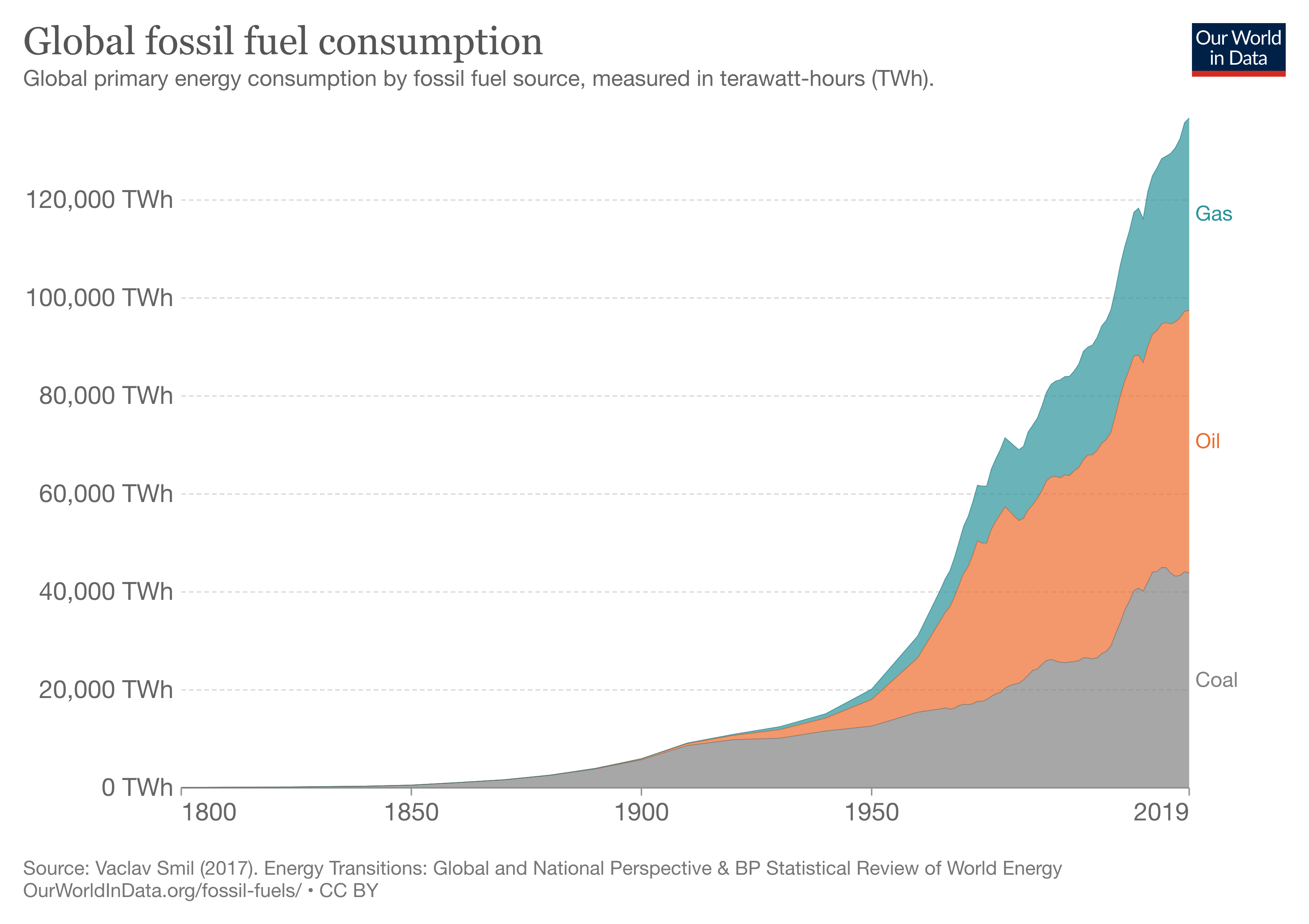

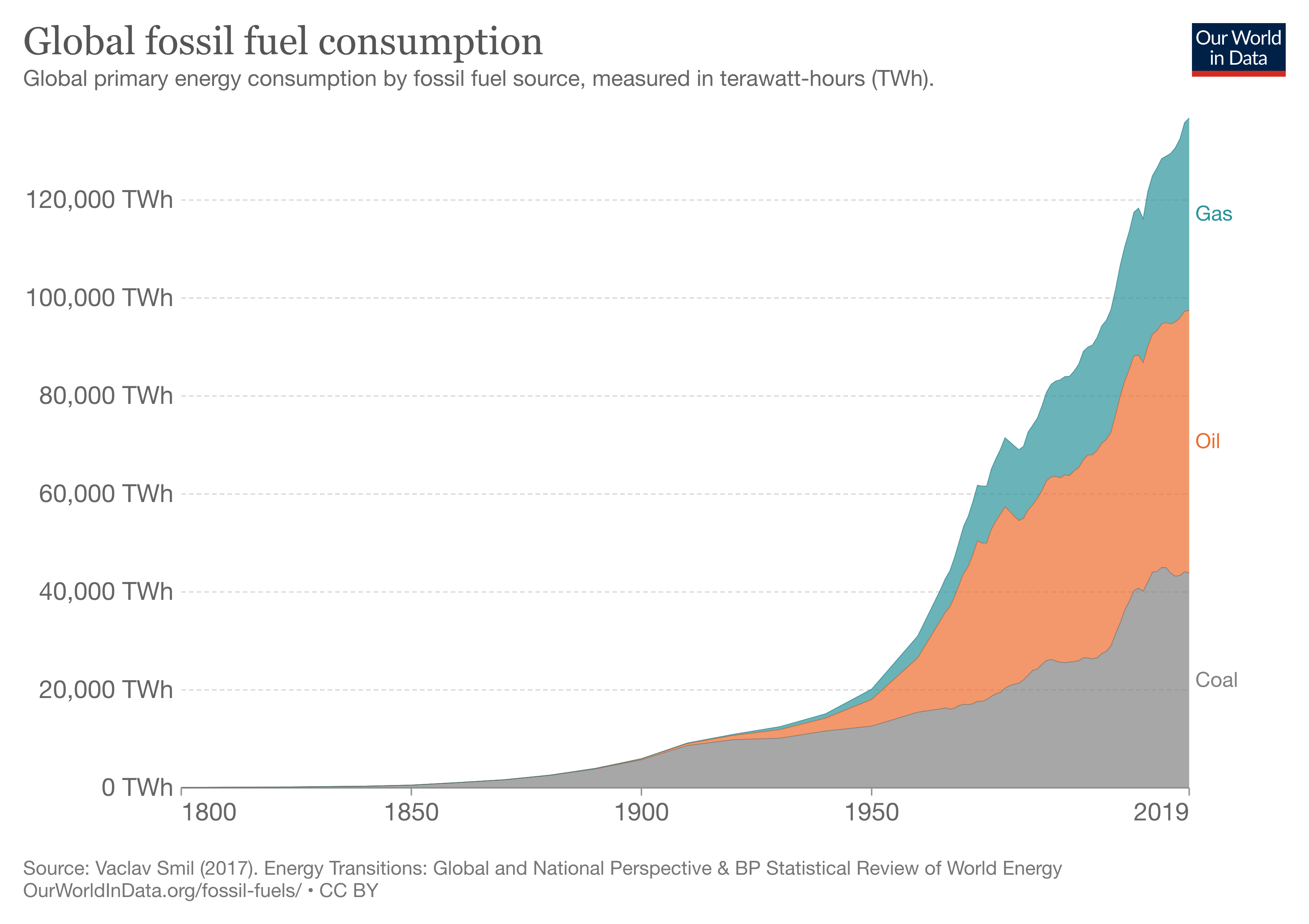

One way to think about this is that climate change was one of the first signals that we had moved into the Anthropocene. We started noticing in the 1950s that carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere was climbing year after year, which was linked to fossil fuel combustion and emissions. That was the moment we realised that the sky doesn’t go on forever. Of course, we all understand that, scientifically, the atmosphere is finite. However, in psychological terms, we were still acting as if the sky went on forever, that you could dump waste into the sky, and it would somehow dissipate.

That is, we believed that humans are insignificant compared to the vastness of the sky. Similarly, we presumed that the oceans are vast, and you could industrialise fishing and extract more and more from the oceans without consequence. Likewise, we thought the forests are so extensive that you could chop away, converting forests into farmland, and there’d always be enough forest left somewhere for the biodiversity of Earth.

Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2020). Published online at OurWorldInData.org

Asking the right questions

The Anthropocene concept is a recognition of the finiteness of all these boundaries. The reason why they're finite is not that the boundaries have shrunk, but that humanity has expanded. Not in terms of numbers — although the population has increased over time — but in terms of human consumption, especially by humanity's wealthiest people. The term recognises this state.

In thinking about how to navigate through the 21st century, we must grapple with essential questions such as, how do we provide for the poorer parts of humanity while staying within the boundaries of a finite planet? How do we reshape our economies away from endless growth and the assumption that the Earth can support such expansion, toward a system that recognises a finite planet?

The Anthropocene mindset

The Anthropocene, as part of our mindset, can work at an individual level. As an individual, you can think and recognise the impacts you have on the planet, improve the amount of waste you recycle, reduce your carbon footprint, and support biodiversity in your neighbourhood and landscape.

However, that is a limited approach. Instead, the term tries to recognise that this is a much larger societal problem while creating a sense of urgency and rupture from the past. There is a tendency to think of environmental change as something slow and ongoing that we need to tackle over time. One framing of the Anthropocene began in the mid 20th century with the rapid surge of industrial activity following the second world war, and it marked something new in human history. It's a rupture with the past where humans are now bouncing against the finiteness of the planet. This requires fundamental shifts in how we think about and design our societies, whereby we stop considering eternal growth the absolute good of societies.

Indeed, the Anthropocene mindset attempts to underline that limitless growth is impossible. It worked throughout the 20th century as we went from having a relatively small global footprint to a vast global footprint. Many of our economic systems were built on that 20th century model. Now in the 21st century, we're hitting the fundamental flaw with these systems. Our old model presumes an infinite planet that we do not have. Overall, we need to start redesigning society at a fundamental level so that it may sustain itself on a finite planet.

Living in a finite world

Photo by fotohunter

How do we tackle the Anthropocene? There are no easy answers. There are certain aspects of climate change where we see clear answers emerge. We're seeing ways of approaching net zero emissions of carbon by the middle of the end of this century. This is partly through redesigning our societies in terms of transport and demand and heating systems. There are also technological advances, and, overall, it’s becoming more efficient and affordable to use non-fossil fuel technologies, such as renewables. So, there does seem to be at least a pathway to a more stabilised future.

Other issues are more challenging to address. How do we bring biodiversity back? How do we find the sweet spot between reducing poverty and supporting human welfare while avoiding the extremes of wealth and consumption that degrade the planet?

There are hundreds of fantastic ideas circulating. While no one knows for sure, I think it is paramount that we adopt this Anthropocene mindset whereby we understand the base condition that the planet is finite. Then, we can work out solutions to tackle this problem.

Denial is not a solution

However, it must start from that first recognition. There are aspects of society that have begun to recognise this, but there are also broad aspects of our societies that do not. For instance, there's a sense that if we deny or ignore the problem, then what worked in the 20th century will continue to work. In this sense, it's like an inconvenient problem that we want to simply ignore. Yet, I believe that humans must shift their framing of the planet and its finite resources.

Moreover, I see a lot of hope. I see a significant shift over the last few years, inspired by the youth movement and the climate movement. Climate change has been a fundamental generational issue, and I see real hope in shifting to a new generation. This generation recognises the finiteness of life on Earth and our duty to find sustainable pathways and navigate this complicated situation.

There are a lot of trade-offs, a lot of things to discuss and work through. And there are many issues that we don't have the answer to right now. Regardless, overall, we need to frame the Anthropocene correctly. We need to maintain a positive attitude and try to find solutions. We cannot just decry what we have lost, but we must find positive pathways to provide for human welfare while maintaining a viable planet.

An ambitious agreement

I was in Paris during the climate change negotiations. Having been to several climate change negotiations prior, I was struck by the breadth of Paris' ambition. Usually, these meetings result in some compromised middle ground where there is moderate progress at best, but also a lot of disappointment.

What came out of Paris was quite ambitious. It was amazing that everyone not only agreed that climate change shouldn't go beyond two degrees but that it ideally should be limited to 1.5 degrees. Implicit in that conclusion is that fossil fuel emissions have to reach zero at some point by around the middle of this century.

Indeed, that is quite profound. Before the conference, the entire framing was around reducing footprints. However, in Paris, there was a fundamental acknowledgement that emissions must be reduced to zero to maintain a stable climate. Fossil fuel combustion has to stop at some point, and there are reserves of oil and coal that must never be burnt – they have to stay on the ground. End of story. That level of ambition was breathtaking and not something I'd seen before.

Was it too much or just enough?

The question remains, however, is 1.5 degrees too ambitious? Potentially it is. We're already at one degree, and we have so much inertia in our energy system that it's going to be challenging to hit 1.5 degrees. We are almost sure to overshoot that target. So, it's partly a framing issue. Do you go for an ambitious target and therefore, end up being slightly more ambitious than you would have been otherwise? Or does overshooting that target cause a sense of despair? One might think: we set a target, we overshot it, the world hasn't quite ended, what's the big fuss about?

I think the last few years have shown that the level of ambition was warranted. While government actions are caught up in discussions and still lagging, we've seen shifts occurring in society overall. With the advent of the climate movement, especially the youth movement, there's an urgency and understanding that we only have a decade or two to solve this issue.

I think the ambition of the Paris agreement catalysed a lot of that enthusiasm. If the Paris agreement had said two degrees, I'm not sure we'd see the level of societal awareness and urgency that we see now. Overall, I think there are hazards in being too ambitious, but I believe there are also benefits, which we have seen emerge over the last couple of years.

Photo by MVolodymyr

Climate denial

Climate denial is a challenge. What climate denial represents to me is a reluctance to leave the 20th century mindset. We saw so much economic growth and an increase in prosperity in the 20th century. This prosperity was based upon the notion that the more you could exploit natural resources, the more you can pour your waste away into the atmosphere and rivers, the better society is as a whole.

The challenging thing is that attitude worked for most of the 20th century, and societies became more prosperous. There has been pollution and other issues, but, overall, human prosperity has increased. To me, denialism is fundamentally a mindset reluctant to move away from that model. This mindset sees anything unaligned to this 20th century model as suspicious, an alien ideology that will break a system that's been working quite well.

I think denialism also encapsulates a rejection of scientific evidence. For example, to believe that somehow pouring our waste into the atmosphere won't have consequences is as ridiculous as pouring car exhaust into a closed room and somehow expecting that it won't have an effect. The size of humanity’s collective metabolic exhaust is so great, and the atmosphere so finite, it's inevitable that our activities are going to have an impact. We've got to follow the best science and evidence of the magnitude of that impact and then try to deal with it.

Beyond just science

Overall, the problem with climate denialism is that it gets wrapped into a culture war, particularly in the US. It becomes part of your identity that you're suspicious of science, and you don't believe in climate change. It becomes part of your cultural and political identity to be wary of society's collective scientific wisdom. Sadly, this is a real turning back on 200 years of scientific progress and enlightenment. It is a rejection of the scientific process using balanced evidence. Instead, denialism considers all evidence to be partisan, suspicious, and somehow part of a conspiracy-based agenda.

So, how do we tackle it? We keep on going at it. We certainly keep the science at the core. That way, it doesn't become a political agenda. It becomes about looking at the evidence, promoting the evidence, and making the scientific method the core of any argument.

That said, part of denialism is generational as well. Ideas that are locked into a particular generation tend to melt away as new generations come on board with an openness to new ideas, for instance, the notion that we live in a finite world. So, to some extent, we must tackle the issues around climate change and climate denialism. However, at the same time, we must look inward, look to the youth, look to the future, look to education systems to try and build up a society that values scientific evidence and recognises the challenges we face. We must confront the future with eyes wide open rather than eyes wide shut, cast back to the 20th century, and not looking ahead to the challenges of the 21st.