The British wanted to ban suttee. They thought that it was an ugly spectacle – but they also had something more specific in mind. The British wanted to know whether the woman who sat on the funeral pyre consented to her death. This fascinated me. Consider British sovereignty, British liberalism and all those traditions and then consider that the initial British statecraft in India was about women and women’s consent.

Gender violence and equality in modern India

Historian of Modern India and Global Political Thought

- The increasing economic freedom of Indian women has coincided with a rise in gender violence, such as the notorious Delhi gang-rape case of 2012.

- Far from being passive victims, however, Indian women are natural leaders, who are front and centre on the country’s political stage.

- Unbound by patriarchal or family structures, it’s in the political arena that women are truly free.

The politics of violence against women

As someone who has been immersed in the question of political violence, I can’t help but also think about violence against women in India.

I don’t see it solely in terms of gender violence, though, of course, it is that. I tend to think about it in political terms. Is there any connection between killing women, either before or after birth, the explosion of gang rapes over the past 20 years and the rise of mass democracy? What is going on? Is there a relationship between what political theorists would call sovereignty, or decisions over life and death, and women?

Suttee and the State

As a historian, I took refuge in the past for my initial plotting of this problem. It struck me that the first major legislation the British enacted in India concerned the practice of suttee in the 1820s.

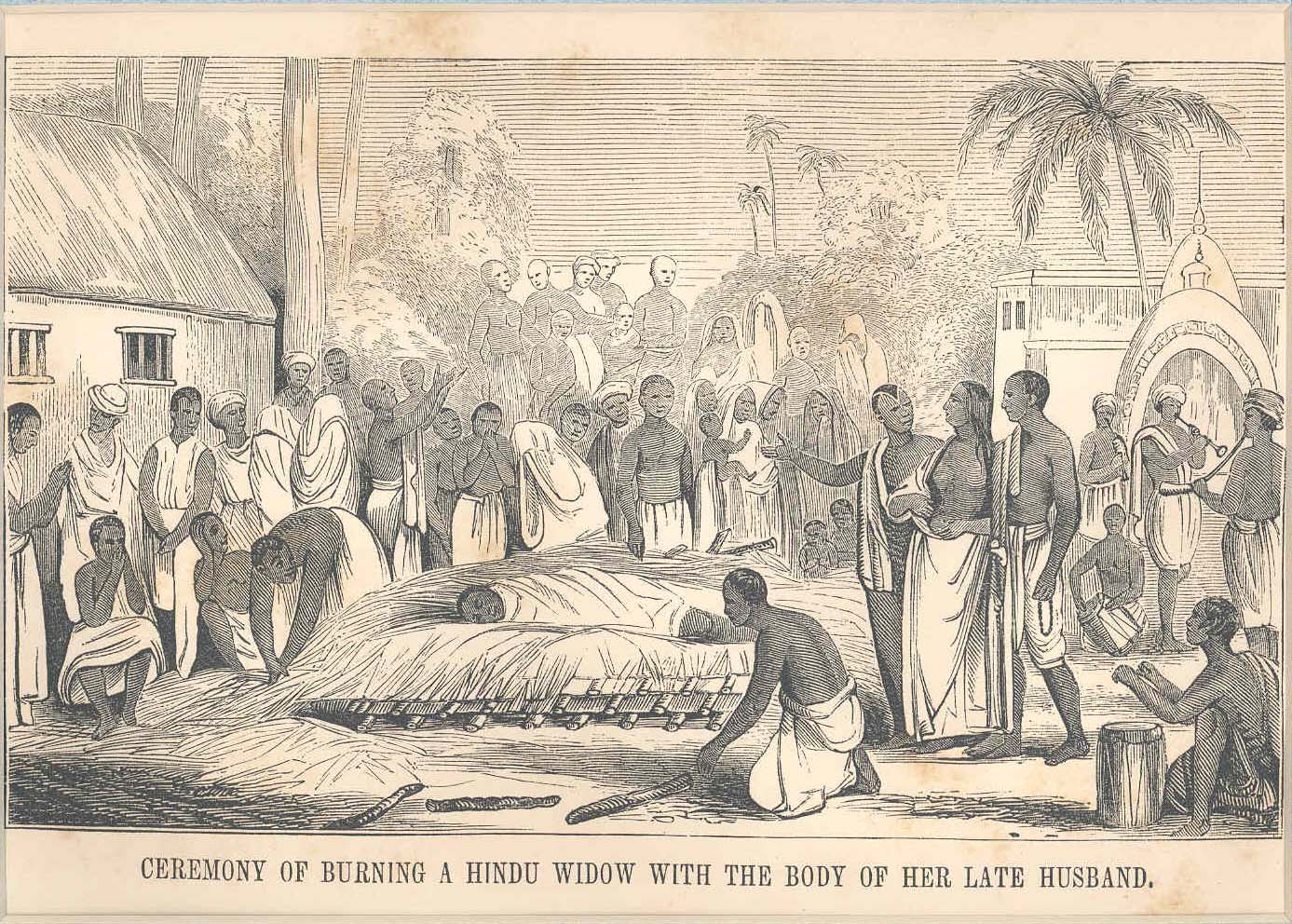

Suttee is highly controversial, not least because of question marks over whether it really existed or was some kind of orientalist fantasy. It refers to the Hindu ritual in which a widow would sit on a funeral pyre and burn with her dead husband.

"Ceremony of burning the body of a Hindu widow with the body of her late husband*; also: *The favorite Wife of Sevajee, preparing for the Suttee," from an English history book, 1851. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

The horrors of gang rape

Contrast that with gang rape, which exploded onto global television screens in 2012 with the Delhi gang-rape case. The world saw what was happening in India.

Again, I was interested in what this was about. Why did this woman, who was simply trying to improve her lot, incite so much rage in a man to the extent that he did not simply rape her but also desecrated and destroyed her body?

In my book, I argue that this shows that the potency lies with the woman in India. This goes all the way back to the suttee debate, because it’s really a question of women’s consent. That consent institutes, as it were, a new liberal compact between the subject and the State. Gang rape is part of this narrative of economic liberalisation and the unleashing of all sorts of passions, as well as actions.

Indian women and leadership

Indian women have finally become what the State wants them to be: economically independent. Modernity and economic liberalisation should mean that they can walk around freely, but, in doing so, they run the risk of being killed and desecrated.

This is not simply a war of the sexes. It could be that, of course, but it also speaks to the relative potency of the woman as the basis of political power in India. If you look at India’s political landscape, it is dotted with female leaders.

Kamala Harris taking oath of office.20 January 2021. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

We’ve just celebrated the success of Kamala Harris – only part-Indian, but we can claim her. This is a kind of globalisation of India, but it has taken until 2021 for that to happen in the great American republic.

Compare that with India. We’re not just talking about Indira Gandhi. Modi has been stopped by a tiny woman in Bengal. She’s a very impressive, if divisive, populist leader. Equally, southern India has produced famous movie stars who have gone on to become effective chief ministers. The death of Jayaram Jayalalithaa led to mass suicides.

So, there are two sides to this coin. There is the desecration side but also the leadership side. Leadership comes easily to Indian women.

Breaking free from the patriarchy

Bengali Actress and BJP leader Roopa Ganguly led her party members in a protest rally protesting against the violence by ruling party in KMC election on April 27, 2015 in Calcutta, India. Photo by Saikat Paul.

It’s really in the political arena that women are truly free. Indian female leaders aren’t bound by family or patriarchal structures. They may have had them at one time, but they’ve left them behind. None are part of some major kinship network, barring Sonia Gandhi, who, of course, is the widow of Rajiv Gandhi. I’m not saying that they don’t have families, but the family values story, or the narrative of having a partner who enables them, doesn’t exist.

After Prince Philip’s death, much of the commemoration centred on what an enabling partner he had been for the queen. Figures like him don’t exist for India’s female leaders, of which there are many.

That speaks to my point about women holding real political and sovereign power in India. It’s interesting to think about how exiting the patriarchal structure has enabled or confirmed political leadership in India.

Mother India or Father Gandhi?

The question of women and the psyche is difficult and richly provocative because India is traditionally conceived of as a mother. Her identity was Mother India from the days of the British Empire, and much of the initial mobilisation in the late 19th century was about restoring the dignity of the “mother”.

Later, Gandhi was regarded as a father figure – ironically so, perhaps, given his frailty and how he embraced effeminacy. Today, with the rise of Hindu nationalism, there’s an ongoing quest to install different fathers of the nation, for example Patel, India’s original strong man; perhaps he’s the true father. It’s like a game of musical chairs, but one in which Gandhi’s status is only confirmed in the end.

India remains, as it were, the mother, but the issue is that, in a democracy, we are not children; we are brothers and sisters. Our relationships with each other are horizontal. As a result, both violent and non-violent competition between the sexes is gaining traction.

The future of Indian feminism

Indian feminism developed in parallel with democracy. In the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, you had many movements demanding equality.

Some of the more contentious debates around gender equity in India have concerned religion and personal law, particularly regarding Muslim women and whether their rights are joined to a uniform set of values that need to be upheld.

The gender question has never been marginal to Indians. It has driven some of the most contentious debates in the country’s history, from suttee in the 19th century to Salman Rushdie and freedom of expression more recently. No one can argue that India is a gender-equal society. But whenever these debates arise, they do pose the question: what would a new feminist politics in India look like?

Discover more about

gender violence and feminism in India

Kapila, S. (2010). A History of Violence. Modern Intellectual History, 7(2), 437–457.

Kapila, S. (2005). Masculinity and Madness: Princely Personhood and Colonial Sciences of the Mind in Western India 1871–1940. Past & Present, 187, 121–156.

Kapila, S. (2021). Violent Fraternity: Indian Political Thought in the Global Age. Princeton University Press.

Kapila, S. (2021). Pew India survey takes us back to one more thing Gandhi, Savarkar differed on. Financial Times.