There was something called a marriage bar. This operated till the 1960s. It said that if a woman was married, she couldn’t work because her husband would be supporting her. This led to the feminine mystique of so many women being ‘just’ housewives and mothers at home, leading to, really, quite a lot of suicides. I needed to think about this in a very systematic way. What I take away from that earliest period at the end of the 1950s is not just the very shocking conditions for women but something more ineffable, in a sense. It became clear to me by reading the census that there was no category for women in the census. You could be a daughter, you could be a wife or you could be a widow. I came across that again recently while reading Shakespeare. In Measure for Measure, the Duke says, ‘You are nothing then: neither maid, widow, nor wife?’ I thought, okay, women are nothing, are no one! So, what are women then?

Feminism: "The Longest Revolution"

Emeritus Professor of Psychoanalysis and Gender Studies

- All women, with or without privilege, are in some way or other disadvantaged. They are always the Other, no one and oppressed.

- A study of the family structure and women’s role in it, provided the basis for understanding that everything personal is also political.

- There are many feminisms around the world but they all have one goal: to struggle against the inequities and the oppression of women.

An unequal life

I started to look at feminism in a systematic way when I first read Simone de Beauvoir. I realised from being a student at Oxford the extraordinary gender disparity that there was between the 1 in 12 students who were women, and the 11 men who were men. All of them back then were dominated by the public-school ethos and hadn’t really seen a woman since they went to boarding school at the age of eight. I wanted to understand a bit about this. Simone de Beauvoir’s book The Second Sex was very much on the agenda of an interest that we all had in French literature.

And so I read Simone de Beauvoir and was horrified. I thought, my God, is it as bad as that here? Is it really as awful as she’s making it out to be? I started work in the late 1950s to look at the situation of women in Britain and I’m afraid I found that it was as bad! It wasn’t only bad in the obvious way of very poor pay. Everyone said it was half pay, but I think, if anything, it was often under half pay because women did much lower jobs and there were huge discriminations. In fact, what had happened was a discrimination that set up a division between women in the family and women in work.

‘You are No One’

Photo by Photographee.eu.

Being the Other

What Simone de Beauvoir had emphasised is that women were the original Other. She said that everybody in relation to one another is sometimes the Other and sometimes the Self, so to speak. And that can shifts places, but not with those who are women, who are, or were always, the Other. I think that’s right, but there’s another side to that Other, which is No One. (That) One is both Other and No One. That really makes for quite a major turn that one was later to use of oppression.

I think oppression goes across all people who are oppressed. There are lots of different groups of oppressed people – and women are one of them. It doesn’t mean that a lot of us are not, like myself, hugely privileged or at Oxford, privileged to be there. We can be privileged. But generically, as women, in what we might call in a term that is not very fashionable now, but in our universal status as women, we’re not privileged. Even with all my privileges, I still feel frightened if I go for a walk at night on my own. I wouldn’t go for a walk at night on my own. Something might easily happen. So, we’re always, as women, in some way, disadvantaged. I think that is what feminism is about. It is about understanding what it is that makes women always the Other and always, as it were, No One.

‘The personal is political’

Once I realised that there was no such thing as women in the census and that we were, in a sense, No One, I wondered where to find them. In imperial China, if anybody knocked at the door, the housewife, the wife, the mother or the widow would call out, ‘No one is here.’ So, No One is very important. No One and the Other are very important. So, I thought, well, where do we find women? Because, after all, we are here. There’s no question about that. Here we are. Where do we find them?

At that stage, in the early 1960s, everybody on the socialist or radical left was saying ‘Let’s get rid of the family.’ There was a terrific movement to get rid of the family. At the same time, paradoxically, there was an enormous number of books being produced on the family. So, I thought, if women don’t exist as women but only as maid, daughter, widow and wife, then we must only exist in the family. That was later to become the hugely important phrase ‘The personal is political.’ That’s almost the most important phrase of second wave feminism. I thought that I needed to understand the family, which is, in a way, a substitute for women. It’s what women do; women do the family. That’s where they are. That’s where they were feeling so absolutely isolated during the 1950s.

The Longest Revolution

A study of women during the feminist revolution led to a deconstruction of the family. It looks at what it is that women actually do in the family, and it sees it not in terms of the pragmatics of what women do, but what, structurally, women do and therefore why they can’t, in a sense, escape from it. The family structure had been a part of their oppression, part of the woman being the Other, part of her being No One.

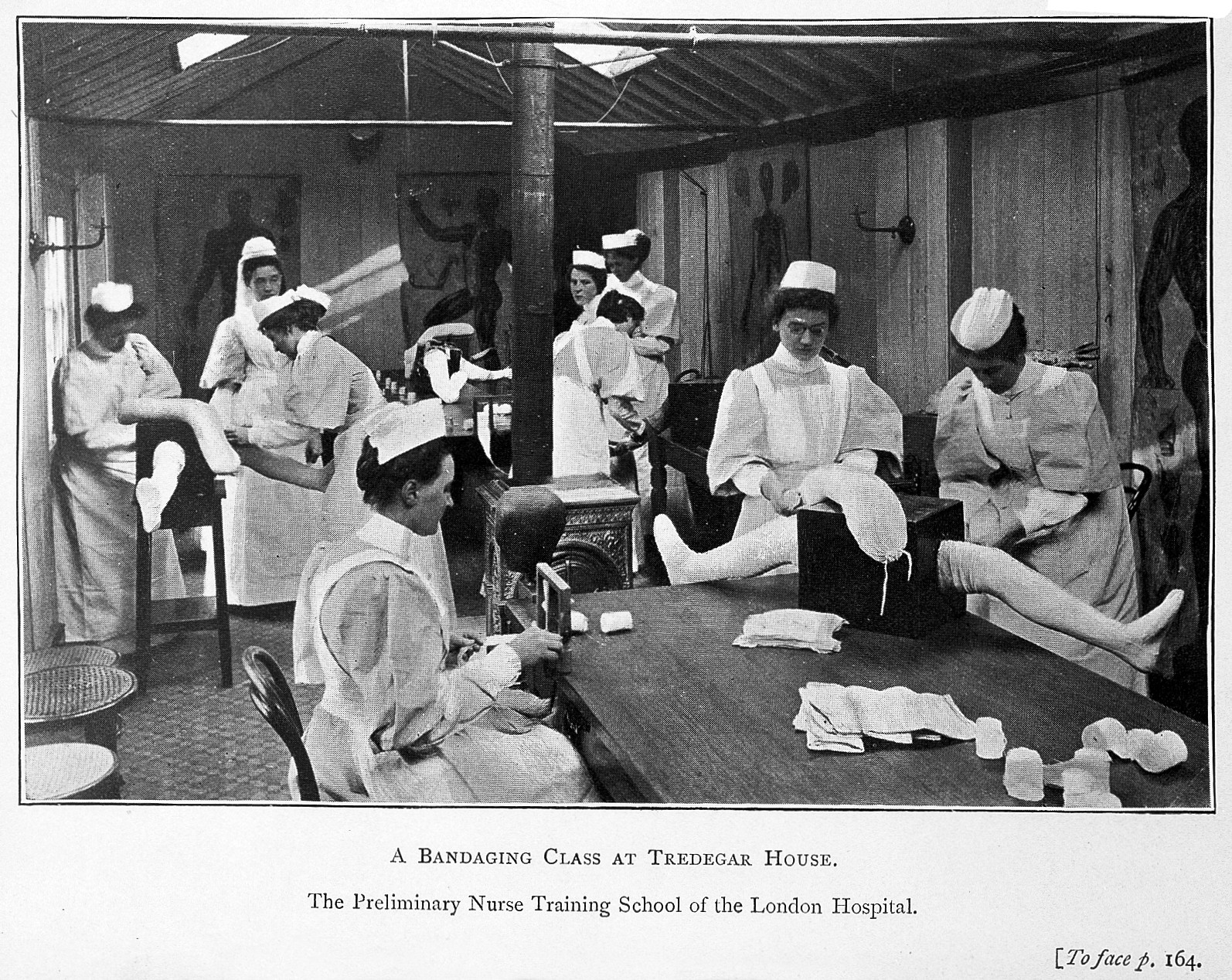

A bandaging class at Tredegar House. Nurse training. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

I looked at women as being surrounded by the world of work. Women have always been in work as well as men. Work, as a factor, was always there. I thought education was the most important aspect of the work situation that needed to be changed for women because it was very unequal at that stage: there were all sorts of privileged places you couldn’t go to. And if you did work better, being a woman it was discounted.

Within the overall circle of work, there was the family. What did women do in structural terms within the family – not in terms of their job as being a housewife but as a structure? What were they there for? I found that they were there for reproduction, for sexuality and for socialising. So, there were three factors. Women had to produce babies, they had to provide sex and they had to socialise children. That, really, was a deconstruction of the situation of women, as identified with the family. I thought of this as the longest revolution.

Radicalism of second wave feminism

I think that the radicalism of the feminist movement and second wave feminism was multiple. Consciousness raising was its creation. It was borrowed from some Chinese practices, developed in feminist terms in which everybody was meant to be equal with one another and share privileged positions. There were mass rallies and demonstrations for equality.

At that point, I didn’t have children. In the local street group that I was in, we looked after one another’s children, even if we didn’t have children of our own. We cooked a meal for one another every night. So, I would say that, from a retrospective point of view, one of the main things that came out of this early moment was the complex and problematic but incredibly important concept of sisterhood. It showed us that relationships with sisters are different from relationships with men.

It is not that individual men are necessarily oppressive; many individual men can be quite feminist. But, nevertheless, just as it is White people who are the oppressors for Black people, however decent any individual white person might be, and however supportive of a Black struggle they might be, it is the white people who are the problem. So it is Men who are the problem. That, I think, is the analysis of patriarchy. With the establishment of the National Organization for Women in 1966, what we had to do was, on all counts, combat patriarchy.

Many feminisms, one goal

Photo by kiwiofmischief.

The question about whether the feminist movement is the left is a complicated one. I know that a lot of people prefer us to talk about the many feminisms. I don’t think there’s one feminism and I believe it’s both a political movement and a theoretical endeavour. I think we’re still working on the theory, as we are on the political movement. What is different is not the feminisms: it’s the situation of women. The situation of women is different in all different parts of the world – hugely different. Therefore, the unity of feminism as such is, for me, a quite simple one. In a sense, it is a struggle against the inequities, the oppression of women and the people who are standing in the position of the Oppressor – men. It’s one feminism which will take different forms, according to the position of women where that feminism arises. It’s obviously very different if you live, say, under a Taliban regime. It is rather different if you are at Cambridge University. But, actually, our endeavour is the same, which is to combat inequity, to combat oppression and to analyse the patriarchy, which can be a mild and relatively pleasant one or a horrific one, but always has at its roots in a certain violence. We should never underestimate that violence. Feminism has to combat that endemic innate violence of women’s oppression.

An ideal outcome

My hope within the revolutionary aspect of the feminist combat isn’t one in which we have a sudden ending, to something like ‘Oh gosh, let’s chalk it up that we’re all equal.’ It’s the re-evaluation of what women do. Women are in a different historical position. I don’t think we’re in a different biological position. But, historically, of course, we’re in a very different position.

If you look at the number of men today who, as doctors, are going to leave the caring profession because it’s just been too much, it is women, as nurses, who are going to stay in the caring profession. What we have to do is re-value the present, the work of caring. We want a different and better society in which women’s contribution is hugely important. How would we live if it weren’t for what women do? We wouldn’t. We couldn’t. We need women’s caring to be valued at least as much as men’s. Men have to go and fight. Women care. Let women care, and everybody care – and nobody fight.

Discover more about

the study of feminism

Mitchell, J. (2014). Woman’s Estate. Verso.

Mitchell, J. (2000). Psychoanalysis and Feminism: A Radical Reassessment of Freudian Psychoanalysis. Basic Books.

Mitchell, J. (1966). Women: The Longest Revolution. New Left Review, 40, 11–37.

de Beauvoir, S., Borde, C. (translator) (2015). The Second Sex. Penguin.