As the technical terminology of slapstick and punchlines admits, joking is not all light entertainment; there’s clearly a savageness to much comedy. Long before Farage made his victory speech in Brussels, the comedian Bob Monkhouse made his famous quip: ‘People used to laugh at me when I said I wanted to be a comedian. Well, they’re not laughing now.’ This not only riffs brilliantly on the comic conceit of self-deprecation, but it also hints at the animating aggressiveness that can so often motivate a comedian in their vocation – the desire to make us laugh, in other words, could well be the hither side of the despot’s desire to stop us laughing.

Politics and the power of joking

Associate Professor in English Literature and Critical Theory

- From the US to Italy and Ukraine, light entertainers have had astonishing success converting into politicians. Trump succeeded by connecting his own resentment of being laughed at with crowds who’ve spent a lifetime smarting from similar wounds.

- Even though joking is often wielded by the powerful against the weak, it’s just as often the recourse of the weak against the strong.

- Today, there is often confusion around whether people are joking or not. Some have taken advantage of this to advance political agendas.

When entertainers become politicians

It was Karl Marx who claimed history repeats first as tragedy and then as farce. He was thinking about political actors who profess one thing but then act in the opposite way. When they or their words appear so debased as to be pretty much meaningless, then history tilts towards the farcical. And that sense is only heightened during those periods when authoritarian leaders assume power by appearing in the guise of light entertainers.

Light entertainers have had astonishing success converting into politicians. We’ve seen this happen not only with the former reality star Donald Trump in the US, but in Italy, where a comedian started the Five Star Movement, and in Ukraine, where a former stand-up became president. The same thing happened in Slovenia, too. And in the UK, Boris Johnson’s compulsive clowning likely not only made him prime minister but gave him extraordinary licence to be buffoonish about it.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson clipping a sheep at the Royal Welsh Winter Fair on November 25th, 2019. Photo by Peter Rhys William.

Humour from the left to the right

It’s not that long ago that liberals thought they had the joking business all tied up. To be right-wing was to be humourless and unable to take a joke, whereas satire was considered one of the liberal arts. But then along came alt-right campaigner Milo Yiannopoulos, who announced, in the run-up to the 2016 American elections, that right-wing politics would no longer present as sincere. Trolling and schadenfreude are what the internet era is for, he said.

And this put liberals in a state of crisis. Indeed, The New Yorker TV writer Emily Nussbaum even suspected that jokes had won the election for Donald Trump. What he’d ingeniously done, she suggested, was to contrast the smug and urbane small-club comedy act of Obama to his own stadium act, where huge crowds could laugh raucously as he jabbed and jibed at the weaknesses and sensitivities of whoever found him or his supporters offensive.

Sharing resentment about being laughed at

Donald Trump’s true political gift was never really for comedy. Rather, it’s for connecting his own resentment about being laughed at by the likes of Obama with crowds who’ve spent a lifetime smarting from similar wounds. In his remarks upon pulling out of the Paris Climate Agreement, for instance, he declared that he was taking this action to stop the world laughing at America. These remarks chilled those who recalled their historical echo in Hitler’s remarks of 1942, when he announced that Jews who had everywhere been laughing would soon cease to do so. Or a more recent echo of the same sentiment might be Nigel Farage’s remarks to MEPs in Brussels after the Brexit referendum, when he trumpeted that those who once laughed at his ambitions are not laughing now.

There’s clearly a kind of politics and a kind of politician who is driven by this desire to wipe the smiles off the faces of whoever they imagine finds them risible. And yet what truly maddens such leaders is the discovery that power is no antidote, because it’s language itself that conditions these unexpected – and often even unintentional – comic eruptions, meaning joking can never be entirely censored. You can no more banish a sense of humour than you can a sense of smell. Which is why, even though joking is often wielded by the powerful against the weak, it’s just as often the recourse of the weak against the strong. Stalin’s Russia was a veritable playground for subversive comedy, for instance.

The democratic nature of comedy

The fact that jokes punch up as well as down means they belong to no one side of the political spectrum. That doesn’t mean jokes lack a political character. Precisely because they can never be entirely mastered or owned, jokes could be said to possess a radically democratic character. Nobody is beyond the reach of jokes, and everyone feels the pinch of this.

It isn’t just despots whose revenge fantasies get roused when you wound their narcissisms. None of us enjoys being laughed at very much. To be laughed at is to feel oneself on the outside, excluded from the fun-loving community of the joke. Few things foment a sense of non-belonging like the feeling that one isn’t in on the joke and so must therefore be the butt of it.

Charlie Chaplin in the 1915 film His New Job. Wikimedia commons. Public Domain.

Is this a joke?

The comment “satire is dead” is about as trademarked to the internet age as everyone’s favourite crying-laughing emoji (which is the emoji that people add to just about anything). And what that’s caused, for some, is real confusion over where jokes belong and who they belong to. The problem for a lot of people is that they can’t tell if someone’s joking or not, or where the boundary between joking and not joking lies. For others, however, that confusion has been a source of opportunity – one that various people have taken advantage of to advance political agendas. The neo-Nazi blog The Daily Stormer, for example, advises its contributors that ‘the undoctrinated should not be able to tell if we are joking or not’. That advice is particularly characteristic of the internet age.

Yet such obfuscation isn’t anything new. Straight after the war, the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre had already observed of racists that they know their remarks are frivolous, but they are amusing themselves, for it is their adversary who is obliged to use words responsibly since he believes in words. This is pretty much the same problem faced by today’s formally fun-loving liberal, who now finds herself regarded as a po-faced snowflake.

The straight person and the jester

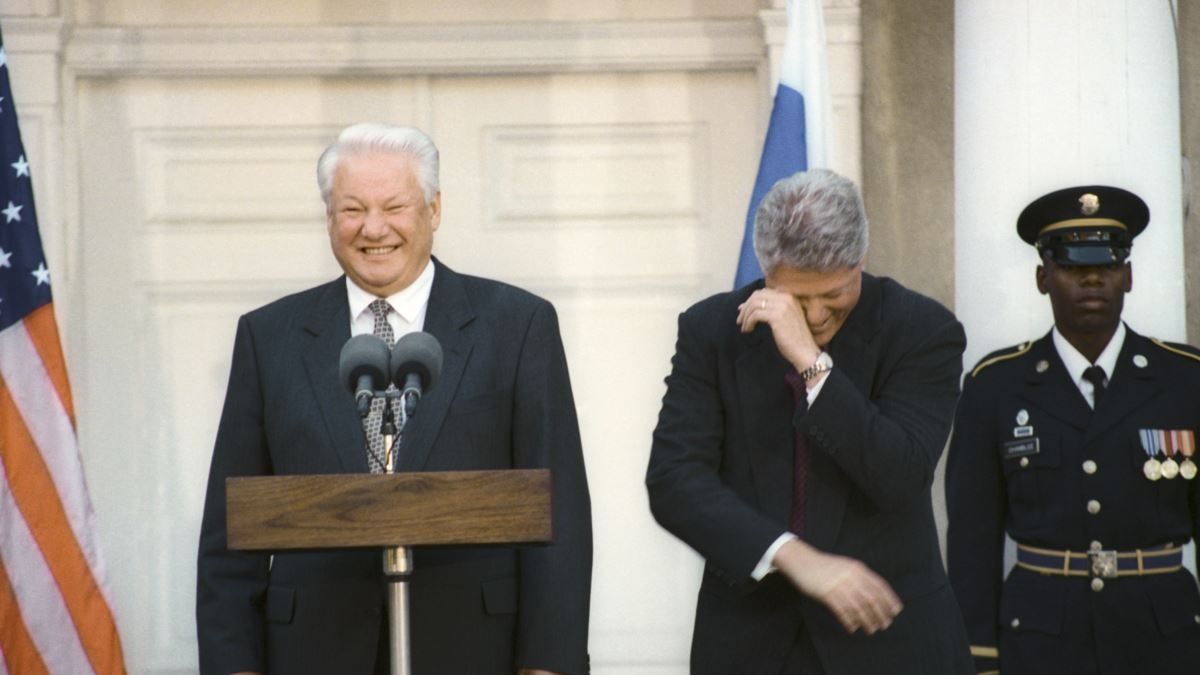

Bill Clinton and Boris Yeltsin laughing at a joke at a press conference 24 October 1995. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

We can see how easily power might get grabbed in this confrontation between the straight person and the jester. No matter where they lie on the political spectrum, the comedian who gives up any pretence of morality or seriousness assumes a critical power that has political implications. The writer Peter Pomerantsev even thinks that smirking at those who still claim to have their Cold War ideological purity intact is what explains a lot of the recent political traction in Putin’s Russia.

The politician, like the stand-up, is better positioned to expose everyone else’s hypocrisies once they’ve given up pretending to care about the exposure of their own. It’s at that moment that the jester can reveal how those of us who profess to believe in our own words may really be playing games with words, even if – or especially if – we fancy ourselves sincere. What the really gifted political joker or satirist ultimately reveals is that we’re all essentially jokers, unless we still think we’re the straight guy, in which case we’re probably the joke.

Joking and justice

Joking has a very strong relationship to power. When joking is going on, we perceive who the butt of the joke is – who is lording it over who – and we can sense the effects of equality or its absence. We recognise when somebody is being used as a laughing stock. So, joking has a very strong relationship to our understanding of power and of justice. And because joking delights in the idea that you can never be sure whether somebody is being serious or not, it allows people to get away with terrible things under the cover of “only joking”.

So, if history is repeating as farce today, we can sense this, I’d suggest, in the atmosphere of a kind of manic, hysterical exuberance. But while it may be exuberant, people are also feeling very frightened. The hysteria therefore has two sides to it: the side that is quaking in its boots at the ways in which history appears to be repeating itself, but also the side that’s just enjoying a kind of revelry and laughter, because words no longer need to attach to actions or even to facts. People are free to say and do what they like, if they wield the power. It’s why joking can inform on the politics of our age almost like nothing else can.

Discover more about

politics and the power of joking

Appignanesi, J., & Baum, D. (2019, February 14). The Politics of Feeling. Special Edition of Granta Magazine, 146.

Phillips, A., & Baum, D. (2019, February 14). Politics in the consulting room: Adam Phillips in conversation with Devorah Baum. Granta Magazine, 146, 55–82.

Baum, D. (2017). The Jewish Joke: An essay with examples (less essay, more examples). Profile Books.