Trujillo was probably one of the bloodiest, most hard-line dictators in Latin America, but also one of the most colourful and folkloric. He loved pomp and ceremony. He designed uniforms for the army – he named one of his children as general of the army when he was 14 years old. He also named his children after Egyptian pharaohs: one was called Ramses, the other Radames. And he had the capital of the Dominican Republic, Santo Domingo, renamed ‘Ciudad Trujillo’. He was a megalomaniac. So, for 30 years, living in the Dominican Republic was a bit like living in a novel that could be considered magical realism or surrealist, or perhaps both.

Conversation about Mario Vargas Llosa

Professor of Literature and writer

- Latin American literature had a marginal place in world literature before the generation of novelists including Mario Vargas Llosa, Carlos Fuentes, Octavio Paz, Julio Cortázar and Gabriel García Márquez.

- Vargas Llosa wanted to explore what living under a dictatorship does to the people in different spheres of power. His most notable work includes Conversation in the Cathedral and The Feast of the Goat.

- What has remained the same, constant, in Vargas Llosa’s life is his commitment to individual freedom, to the freedom of writers, of thought and of expression.

A remarkable generation

Mario Vargas Llosa belonged to a remarkable generation of Latin American novelists. These were novelists who were born between 1910 and the late 1930s, including Carlos Fuentes, Octavio Paz, Julio Cortázar and Gabriel García Márquez – several of them Nobel Prize winners.

Before 1950, Latin American literature had a pretty marginal place in world literature, and that changed with this incredible generation, with people like Vargas Llosa, García Márquez and Cortázar, who were incredibly cosmopolitan. Vargas Llosa, for instance, lived in Paris starting in the late 1950s, then in London, Barcelona, back to Peru, and he now lives in Madrid. Cortázar lived in Paris for a very long time. Fuentes moved around and lived in the US and Europe. Paz was Ambassador to India. Remarkably, these writers not only brought Latin America and its culture in contact with the rest of the world, but they actually brought an incredible number of important world writers to Latin America as well.

© Arild Vagen via Wikimedia Commons

A political writer who sidestepped socialist realism

Mario Vargas Llosa is one of the foremost political writers. When he was very young, he was a passionate reader of Jean-Paul Sartre, the French existentialist, and was very taken with littérature engagée, literature that is committed to politics in some way. Vargas Llosa wanted to avoid falling into socialist realism – this very blunt, uninteresting form of bringing politics into literature that would basically hammer the reader over the head with a message or a political position.

In his first novel, Conversation in the Cathedral, written in 1969, he decides to write about the dictatorship in Peru. By the 1950s, Peru had lived under the dictatorship of Manuel Odría for about eight years. He was a pretty unremarkable dictator – grey, uninteresting – and this was part of what attracted Vargas Llosa to him. He said, ‘It’s very easy to be folkloric when it comes to Latin American dictators. Some of them even have delusions of being Egyptian pharaohs.’ But Odría was very boring, standard and everyday. So, Vargas Llosa wanted to explore what a dictatorship does to a population, even when the dictator is just a bureaucrat.

A dark novel

Conversation in the Cathedral has over 80 characters from all kinds of social classes and walks of life – politicians, government ministers, industrialists, rich people, maids, prostitutes, chauffeurs, people who work in the dog pound. One gets an X-ray of Peruvian society in all of its dimensions. Vargas Llosa wanted to explore what living under a dictatorship does to the people in different spheres of power, and he manages to do that and at the same time tell a very good story.

The story is of Zavalita, who is something of an alter ego for Vargas Llosa. Zavalita is a young, enthusiastic, very smart young man who has literary ambitions. He decides to get a job working at a newspaper called La Crónica and begins to write articles about politics. Very quickly, he gets disillusioned not only by journalism and by politics, but also by his country. It’s a very dark novel.

Vargas Llosa’s political position

Many people think that Vargas Llosa had a turn at some point in his life, because when he was a university student, he was a communist. He was a member of a very radical leftist group in the University of San Marcos in Lima. In recent years, he’s become known as a staunch defender of liberalism, especially economic liberalism. So, people wonder how a communist became a liberal. However, what I see is a continuity: what has remained the same, constant, in Vargas Llosa’s life is his commitment to individual freedom, to the freedom of writers, of thought and of expression.

One of his first run-ins with the left was over Cuba. Vargas Llosa began to travel to Cuba in 1962, a few years after the Cuban Revolution. He was actually one of the very first important writers to show a commitment to the Cuban Revolution as a cultural project. But he broke with it in 1968 when there was a debate, which all started when the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia. Of course, everyone thought this was horrifying and Vargas Llosa protested against it. He wrote a column criticising it and then got a message from Cuba that he couldn’t criticise the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia because Fidel Castro had defended it. So, Vargas Llosa had to make a decision: ‘Do I support the Cuban Revolution or do I defend my individual freedom as a thinker, as an intellectual, as a writer?’ He chose the latter.

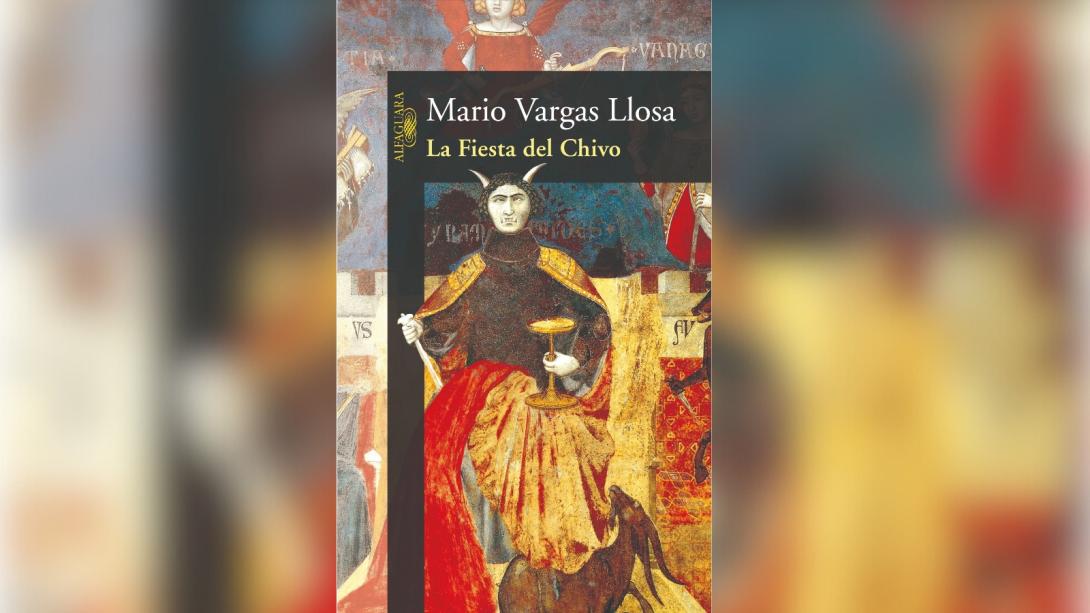

The Feast of the Goat

The Feast of the Goat was written in the late 1990s. In it, Vargas Llosa branches out to a country that he didn’t really have an association with: the Dominican Republic. Up until that moment, he had written a lot about Peru, about Latin America in general, but never about the Dominican Republic. So, why did he choose to write this novel? In the 1970s, he was invited by French television to travel to the Dominican Republic to do research for a series of television films that were going to be made. He began spending time in Santo Domingo. There, he heard many stories about the dictatorship of Trujillo, who had been murdered in 1960 after ruling the country from the 1930s until 1960.

© Wikimedia

A novel about a mad dictator?

People turned out to see him and receive him almost as if he were a god. There were throngs of people who followed him everywhere. They adored him. They wanted to touch him. When he went to little villages outside of Santo Domingo, the farmers would sometimes bring their young daughters and put them up for Trujillo to take – they would consider it a great honour if he spent the night with them.

When Vargas Llosa heard about this, he couldn’t believe it. But then he began to do research, to talk to people and consult newspapers, and it turned out to be true. The dictatorship was so mad that people had fallen into this very perverse relationship with the dictator.

Vargas Llosa decided to write a novel about it, and one of the main troubles he had is that he didn’t think he could write the book in a way that it would be believable. The reality was so unbelievably twisted, perverse, yet folkloric, that he thought that if he put it in the novel, it would read like a bad novel because no one would believe a word that was written.

Telling the story from a woman’s point of view

Vargas Llosa found a very interesting device. He decided to tell the story from the point of view of a woman – Uranea Cabral, the narrator of the story. Uranea is a very successful lawyer in New York, who left the Dominican Republic when she was an adolescent and lived her whole life outside of the Dominican Republic. The novel begins when she returns after many years of being absent and goes to visit her ailing father, who had been a minister to Trujillo.

As a little girl, Uranea lived under Trujillo. Her father was a minister, so she was pretty close to the president. Through her, Vargas Llosa tells the story of what it was like to live under that dictatorship. It’s an incredible device and an incredible solution, because it’s also one of Mario Vargas. Just as with most feminist novels, the entire point of view is from the experience of a woman. This allows the story of the dictatorship to be told from the point of view of a woman and a citizen of the Dominican Republic. This is quite unique in that we have lots of novels in Latin America about dictators, starting with Miguel Ángel Asturias’s El Señor Presidente, but this is the only one I can think of where it’s the point of view of a woman that tells the whole story.

A passion for ideas

Vargas Llosa is very different from other writers of his generation. For instance, García Márquez only wrote novels; Cortázar wrote novels and short stories; but Vargas Llosa has written many novels. He tried to run for the presidency of Peru in 1989 and lost it to Fujimori. He acted in his own play recently, in his eighties, in Madrid. He has written about politics. He has written a beautiful autobiography called ‘El Pez en el Agua’, A Fish in the Water, in which he reflects on his life, and on the failed run for the presidency.

© Mauricio Macri and Mario Vargas Llosa. 23 February 2017. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Vargas Llosa wears many hats, but all the books and all the projects, and everything he has done in life, have one thing in common: a passion for ideas, for critical thinking and for the relationship between writing and politics.

Discover more about

Mario Vargas Llosa

Vargas Llosa, M., & Gallo, R. (2018). Conversation at Princeton with Rubén Gallo. Alfaguara.

Vargas Llosa, M., & Gallo, R. (2017). Conversation at Princeton with Rubén Gallo. Fundación Telefónica.

Vargas Llosa, M. (1991). A fish in the water. Faber.

Vargas Llosa, M. (2000). The feast of the goat. Faber.

Vargas Llosa, M. (1993). Conversation in the Cathedral. Faber.