Works on Proust

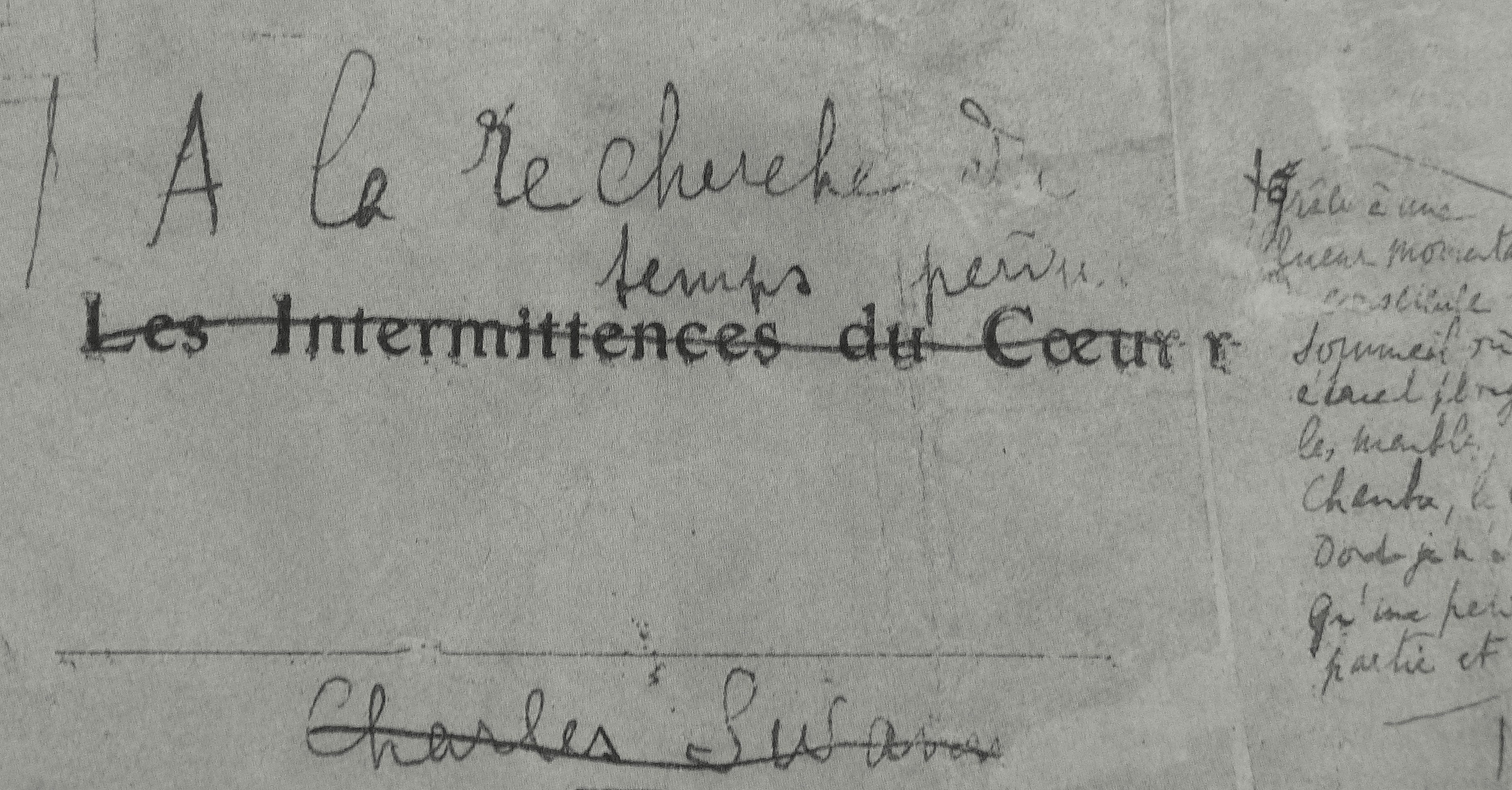

When I began to read Marcel Proust in my early 20s, I was overwhelmed. À la Recherche du Temps Perdu is a novel in seven volumes. It’s thousands of pages. It’s a work of its own. One of my colleagues always jokes and says that you need a sabbatical just to be able to read the entire novel. But what I found even more remarkable was the scholarship on Proust. You could almost fill an entire library with all the books that have been published on Proust on almost every subject imaginable: Proust and architecture, Proust and religion, Proust and cathedrals, Proust and painting, Proust and gastronomy, Proust and Rome – Proust. It’s unbelievable everything that people have found in À la Recherche du Temps Perdu. It seems like everything has been written. But then I realised there’s one thing that has not been written about: Proust’s relationship to Latin America.

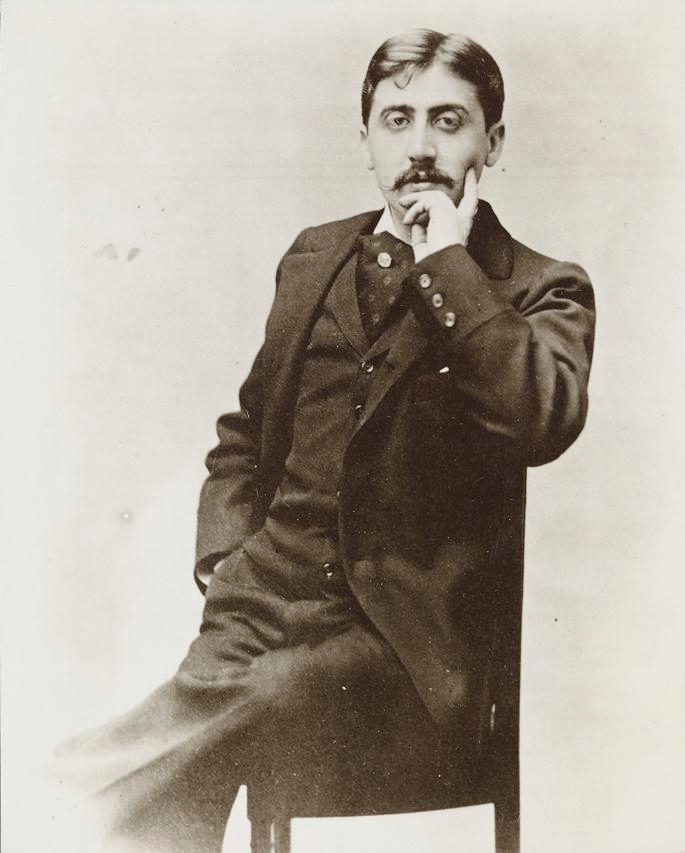

Most people who know Proust would say, what connection could there be between Proust and Latin America? He seems like the archetypal, late 19th century French writer. Proust never travelled to Latin America. We only have proof of him having one boyfriend, the musician Reynaldo Hahn, who was a very famous composer in the early years of the 20th century – a bit forgotten outside of France today, but someone who’s still very alive in French music.

What interested me was that, in reading about this relationship between Marcel Proust and Reynaldo Hahn, most biographers would almost write as a footnote the fact that Hahn was born in Venezuela. This blew my mind, because if you think of Proust with a Venezuelan boyfriend, it’s a very different image from the Proust that one usually gets in France, which is a 19th century bourgeois – a bit of a stuffy picture. Imagining him holidaying in Brittany with his Venezuelan boyfriend is a much more playful picture. That’s how my book began, trying to understand what it meant to think of Proust having a Venezuelan boyfriend.

Gabriel de Yturri

It turns out that not only did Proust have a Venezuelan boyfriend who, by the way, was truly Venezuelan – he was born in Venezuela and came to Paris when he was about four, and spoke Spanish at home – his family was Venezuelan and he was friends with many other Latin Americans in Paris.

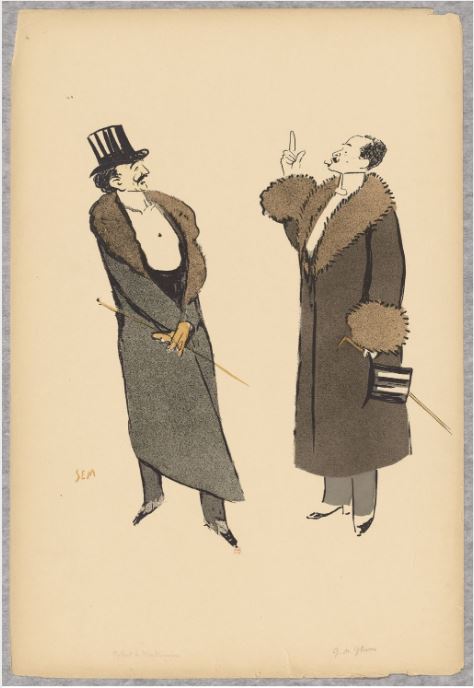

In addition to Reynaldo Hahn, Proust was very close to a number of Latin Americans who were very important for him and for his work. There was Gabriel de Yturri, who was an Argentinean who arrived in Paris penniless and a few weeks later ended up living with Robert de Montesquiou, one of the most aristocratic, rich, important and snobbish of the characters living in the turn of the last century in Paris.

He’s the model for the Baron de Charlus in Proust’s novel – this incredibly arrogant but very smart and cultured man who loves to put people down. He’s quite sadistic and dismissive of everyone. Proust was a bit intimidated by Montesquiou, but he felt much closer in age, and in sensibility, to Yturri.

José Maria de Heredia

José Maria de Heredia is known in France as a very important poet associated with the Parnassian Movement and author of Les Trophées, which is still read in schools today. What no one really remembers is that de Heredia was actually Cuban. He was born in Santiago de Cuba. He came to France for school and then stayed and managed to really integrate and become an important figure in French letters.

He was much older than Proust, and when Proust began to write, as a teenager, he told one of his friends in a letter that he had two models for the type of writer he would hope to become. One was Montesquiou, because he was elegant, had great houses and threw lavish parties. The other was de Heredia, because he was also a very elegant writer. He hosted a salon, he had a very beautiful apartment and he was recognised by everyone. I like to think that, as a young man, Proust chose a Cuban as a literary model. This changes our perception of him again.

Ramón Fernández

Ramón Fernández was the son of the Mexican ambassador to Paris. He was born in France as a Mexican citizen and grew up in France, speaking French and passionate about French culture. T. S. Eliot said, at one point, that Fernández was the most interesting critic working in France. He was very dynamic. He worked for the NRF – he was one of the youngest people publishing in the most important literary journal.

Fernández went to see Proust to try to get to know the person and the work. You can see proof among Proust’s very close group of friends and associates that his friends included a Mexican critic, the Argentinean lover of Montesquiou, a Cuban poet and a Venezuelan lover. So, suddenly, we realise that Proust was surrounded by Latin Americans and quite in touch with Latin American culture. This is an aspect of his life and work that no one had really explored.

An insider and an outsider

One of the most interesting things in the novel is the position of the narrator. They’re both an insider and an outsider. I think it’s almost the only perspective that a good writer can have on the world. You need to know it enough to be able to describe it in detail, but you also need to be a bit detached from it to be able to criticise it and talk about it with distance and with irony. This is exactly what Proust does, in part because this was his position in life. Proust was both Jewish and non-Jewish: his mother was Jewish and his father was a bourgeois gentile.

One of my theories is that Proust actually learned quite a bit about this position of alterity, first from Reynaldo Hahn, by watching what it means to be a Venezuelan in Paris. Hahn spoke perfect French. He was educated at the conservatoire. There was nothing in his relationship to language that would mark him as a foreigner. Yet, for instance, when his first opera was presented in Paris in the 1890s – L’ÎIe du Rêve, which he wrote when he was 26 – the newspapers were cruel. They called him “un petit vénézuélien”. They called the opera “une opéra exotique”. They said why does this tropical, exotic young man want to come to Paris to teach us about opera?

Proust learned a lot about what it means to be fully conversant in the culture in which you’re living, but that you may have other cultures that you are also conversant in and still be marked an outsider. He learned what it means to be both an insider and an outsider.

Proust’s “theory”

Proust had a very funny theory about what it means to be a Latin American in Paris. He thought it meant exactly the same as being Jewish in France or in Paris, because these are differences that are not immediately perceptible, either at the level of language or of bodily marks. There’s nothing that visually makes either a Jewish person or a Latin American, but it’s a difference that is much more subtle and that somehow appears suddenly in the middle of a conversation.

There’s a very beautiful passage in À la Recherche du Temps Perdu in which the narrator is eavesdropping and reports a conversation between Madame Verdurin and her husband. At one point, he says, ‘I cannot tell how the conversation ended because Madame Verdurin used a word that I could tell was private language between her and her husband, one that I could not understand.’ The narrator then makes this incredibly puzzling elaboration and comparison.

He compares it to when a family from the countryside that has lived a long time in Paris and speaks perfect Parisian French, suddenly, in the middle of an intimate conversation, says a word of patois – country dialect – and then you realise they are different. Another example would be when a Jewish family that’s perfectly integrated, and doesn’t follow any rituals, suddenly, in a private conversation, says a word of Yiddish or Hebrew. Or when a Latin American family in Paris, also assimilated, suddenly says a word in Spanish.

The narrator establishes an equation between using Yiddish words, Spanish words and patois as three groups of people who can be completely assimilated in Paris until one word gives them away.

A more irreverent, playful Proust

Proust is one of the funniest authors I’ve ever read. He’s irreverent. He mocks everyone. There’s a very cruel sensibility to the novel, in part because he was very interested in the cruelty that is at the base of French society and the world of the salons. It always surprises me when I hear reverence or stiffness in the way many people talk about Proust. We could think of Latin America as a way of breaking that and maybe getting at the Proust that is much more playful, irreverent, funny – and maybe tropical in a way.