The origins of the novel

The 19th century novel is central to the age, and indeed we could say that the 19th century, or the Victorian age, is in fact the age of the novel – though, of course, we have to look back to its earlier antecedents, to its origins. Some people would locate those in the classical world, but it's more usual to say that the 18th century – the great age of empiricism, of the value of experience, of a commitment to ordinary life rather than to universals – is where the novel begins. Whereas the 18th century novel takes many forms, such as romance or the documentary realism of Defoe, the 19th century novel develops new forms and new ways of telling its readers about the world. We retain the centrality or the commitment to modes of experience, but the development of realism is hugely important.

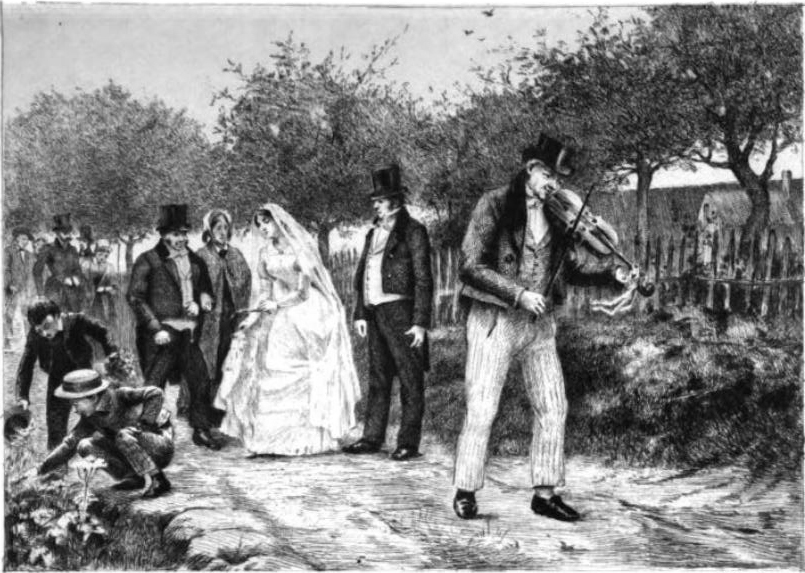

Realism is at the heart of the 19th century novel. The term “realism” was coined in France and is actually a literary movement in the 1840s and beyond, but I don't think we need to tie realism to that particular moment. It extends the concern in the 18th century with the value of experience, with a commitment to the things of everyday life. The writer Stendahl in the mid-19th century said to imagine the novel as a mirror journeying down the road. It would reflect both the sky and the gutters and puddles. Of course, the mirror is also a way of mediating, of representing, and I think that's what we need to remember about literary realism: it is as much a construction of the world as it is an imitation or a mirroring of it.

The construction of reality is exemplified by George Eliot in her novel Adam Bede in the mid-19th century, where she also takes up the image of the mirror. She pauses her tale to ask us to think about a Dutch painting, where we have an old woman who may be eating her solitary dinner, and to think about the light that falls on her cap and on the ordinary things about her. This, she says, is her commitment to realism. She goes on to say that the realism is what is mirrored in the minds of men, so the realism is also part of the world of consciousness, of psychology, of thought. It's no unmediated reflection of the world, but something that gets mixed up with our desires, dreams, wishes and fantasies.

World of romance

In Adam Bede, Eliot makes a very direct declaration of how we should think about realism. All her fiction shows that commitment to realism, but very often combined with something that is seen to be opposed, but also in relationship to it, which is the world of romance. Romance and realism go along the journey together. So, for example, if we take her novel, Silas Marner, it is the story of a working man. It is the story of his ordinary and everyday life, but it is also combined with a fairy tale structure: the loss of the miser’s gold, the discovery of a child, and a tale in which the miser, Silas Marner, is opened up to the world of community, to the world of human beings, and away from his narrow preoccupations. Eliot is, above all, concerned with human sympathy, with how it is that we move from our individual solitary being and connect up with the world of things, the world of men; I think that, for her, realism is the mode of that connection.

The individual and society

If we take Elliot's two greatest novels, Middlemarch and then the later Daniel Deronda, both give us heroines who, though they are very different types, have to struggle with their own fears and the narrowness of their experience in order to attempt to connect with a wider world. The world of Middlemarch is the world of provincial England. Deronda, which is the later novel, from 1876, moves us much more into a world we could think of as modernity, and it's a novel which is restless in ways that Middlemarch is not. Middlemarch is the more rooted novel. In Daniel Deronda, the world of the provincial, the world of the regional, is no longer enough. It moves towards a cosmopolitan European world, though with a sense of what is lost in that restless spirit.

Flaubert is often seen as the archetypal realist novelist, at least in a novel like Madame Bovary, but Flaubert says in a letter that, although he is always called a realist, he actually hates realism. What he gives us in Madame Bovary is Emma, who is caught in her provincial world but dreams of something so much larger. Of course, in the end, she is punished for that. She is punished for her romanticism. Flaubert talks notoriously of saying, ‘I am Madame Bovary.’ He, too, was trying to say that the romantic is what takes us out of the ordinary ordinariness, the everyday life-ness, and gives some colour to what would otherwise be banal.

In Middlemarch, Eliot gives us a heroine, Dorothea, who dreams of a life much larger than the one she has, but she seeks it through her marriage, which goes terribly wrong. She marries a man who is much smaller than she imagines him to be. Eliot, who escaped her own provincial upbringing to become the great writer and intellectual that she was, never allows her heroines those freedoms from constraints. They always remain inside the narrowness of their worlds, however much they dream of freedom from them. At the end of the novel, we are told of Dorothea being in one of those unmarked graves of people who do good, but whose marks on the world are very slight.

George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda

Daniel Deronda, Eliot's last novel, is this restless world, and it is a novel which is very complex in its structural loopings. The way that the story is told to us is not the way that the narrative has, as it were, worked itself out through time. It ends with an entire openness with the hero, Daniel Deronda, going off to found a new world in Palestine and with the heroine, or anti-heroine, Gwendolen, who is very much punished for her own narrowness, her own mercenary-ness, saying, ‘I will be better,’ so, standing on the threshold of a new world, rather like the new women who would come to dominate late 19th century fiction into the early 20th century, and the sort of sense that for women their time had not yet come. Olive Schreiner's Story of an African Farm’s heroine, Lyndall, says she was born 50 years too early, and that is true also for Thomas Hardy's Sue in Jude the Obscure – we are born too early. There’s a sense of desires, wishes and needs that are not yet to be met by society, but they will be in some time to come, and that is the utopian hope.

Henry James wrote a conversation about Daniel Deronda, where his three figures, two women and one man, debate the pros and cons of the moral, its greatness and also its flaws as they are perceived. What Henry James says about Gwendolen and Daniel Deronda is that Eliot makes her narrow and then punishes her for being so. He was worried, as other critics have been, about the two dimensions of the novel, which is Gwendolen’s story, the English part of the story, as she marries the sadistic aristocrat Grandcourt, and then the story of Daniel Deronda, who discovers his Jewishness much later in the novel, discovers his mother and goes off to found the Zionist world. Although I think those two parts of the novel are absolutely imbricated, for James I think there was the sense that actually what he was interested in was less the Deronda part of the novel than the Gwendolen part – her marriage to the sadistic aristocrat Grandcourt. He creates his own heroine, Isabel Archer, the idealistic American who comes to Europe, in the image both of Eliot’s Dorothea and of her Gwendolen, and a young woman he calls Isabel Archer affronted by experience. She marries an American, Gilbert Osmond, who turns out to be as sadistic and manipulative in his own way as Grandcourt is, but at the end of the novel she again hovers on the brink. We don't know how her story will unfold. That open-endedness is also what James is interested in, which I think he takes, in part, from Deronda’s own open-endedness.

Modernism in making fiction

The move to modernism in the novel is towards a sense that character cannot be fully known, so whereas Eliot gives us characters of immense depth and richness there is the accusation that she is too knowing about them, that there are not worlds that she cannot imagine of those characters. The modernist novelist is much more relativist, more sceptical, perhaps, with more of a sense that there are areas which cannot be known or that we are multiple in our selfhoods. The modernist writer Katherine Mansfield talks about her own multiple selves. Which self? She says, there is no single self. One difference would be the sense of multiplicity rather than, perhaps, the unity of selfhood.