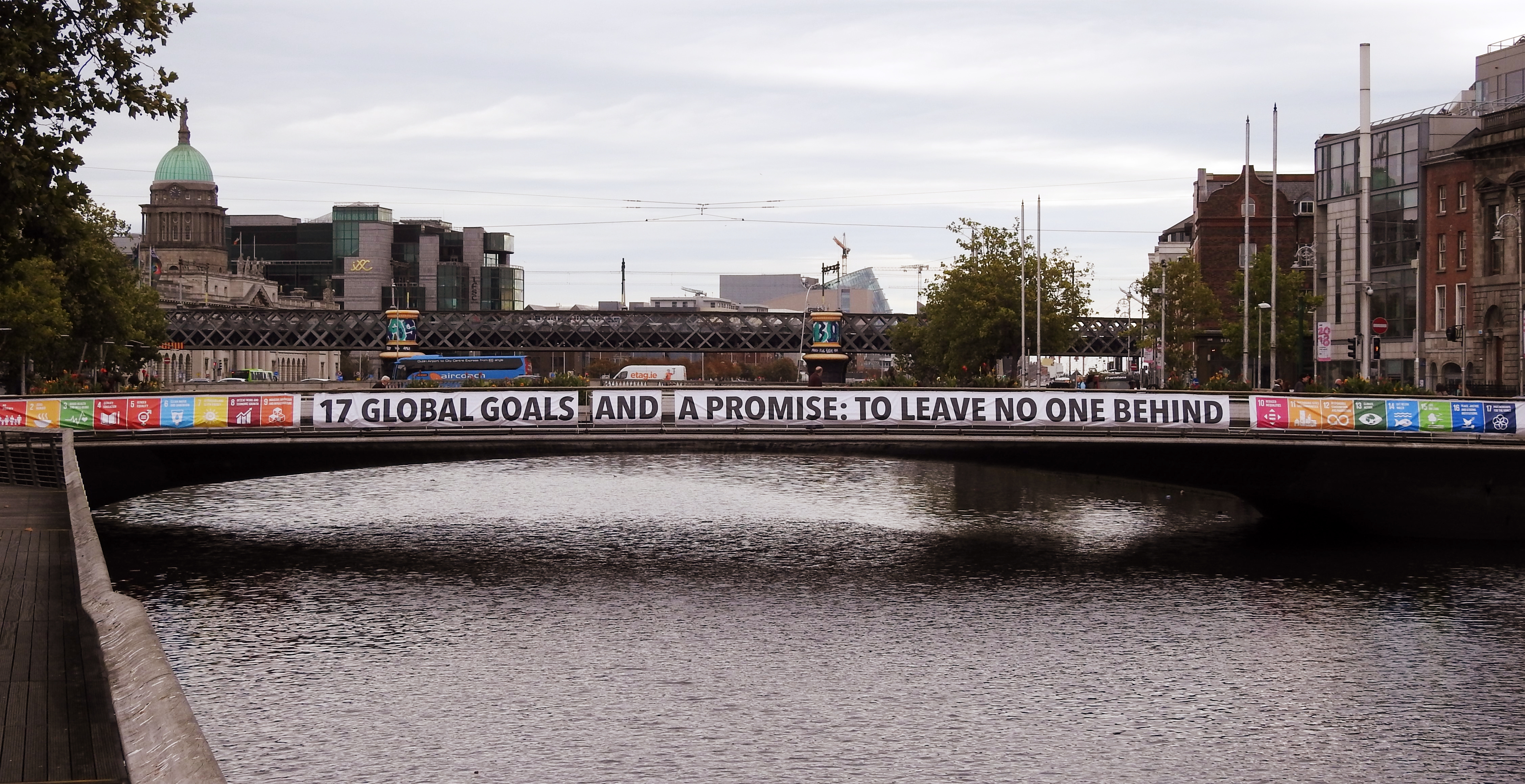

Hopefully we’re aware enough and knowledgeable enough to mitigate and reduce our emissions in ways that also improves the quality of life for people around the world. Think of the Sustainable Development Goals of equality, regarding gender, race and poverty. We have this opportunity to design a world where we do limit the negative consequences of a low-carbon transition or improve the equality of opportunity around the world. So, it’s an incredible moment in time – we can choose the future.

And we have the information. We have the tools. We have many of the technologies – we have to work out which ones to scale up, how to make them efficient, how to make them cheap, how to rapidly move to new technologies in a short space of time. But we know from the pandemic how quick we are to adapt to new situations and how resilient we can be psychologically. And in terms of the way we live our lives, the changes that we’ll make for climate change will not be as rapid. They will not be occurring over days and weeks, like for the pandemic. They will be over months and years. So, there will be time to get used to the changes, to adapt, to find the advantages as well as the challenges. Having cancer and having chemotherapy made it really tangible for me how to weigh up uncertainty about the future, and also the challenges of addressing climate change.