There is always pressure on law. The laws of war are therefore always in a crisis of compliance, because states are always tempted not to stick to the rules. States have good reasons to stick to the rules, for instance, wanting the embrace of legitimacy that law can bestow. Yet, it is always an uphill battle to demand compliance with the laws of war. Even against that backdrop, the war of Russia in Ukraine and the current military operations of Israel in Gaza are causing a perfect storm for international law that makes that crisis much more dangerous.

Violation of the laws of war

Professor of Global Security

- Law on its own is no silver bullet. It can neither prevent war nor make it morally acceptable.

- The duty not to commit genocide is not only owed to the state where a genocide is being committed. The duty not to commit genocide is owed to humanity at large.

- The most urgent and straightforward thing that states can and should do right now is withdraw support from parties to a war that, through their conduct, provide reasonable grounds to believe that they are not complying with international law.

Extraordinary state of threat

It is important to understand that when states are at war with each other or with non-state armed groups, they think of themselves as in an emergency, in an extraordinary state of threat. In that context, there is always pressure on the normal rules of politics.

© Gorodenkoff via Shutterstock

Enforcement challenges in Ukraine

These two conflicts pose distinct challenges for international law. If we start with Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine, it is really a particularly blatant violation of the prohibition on the use of force. It is, in a sense, the “original” case of inter-state war that law seeks to prohibit: one state invading another with the purpose of conquest and of annihilating that state as a sovereign entity in its own right.

© Giovanni Cancemi via Shutterstock

This is the case of a war that the law must be able to deal with. At the same time, the mechanisms for enforcing international law, for demanding compliance, are particularly weak in this case, because the aggressor is a nuclear-armed great power that is also a permanent member of the UN Security Council. International law is not enforced in the way that national law is enforced, but there are still mechanisms for enforcement. These have proven to be particularly weak in this context. It is difficult for third states to intervene in this conflict, because they fear nuclear escalation by Russia. The Security Council is unable to respond to this conflict, because Russia has a veto over what the Council decides. The normal channels of enforcement, the institutions of international law that are charged with demanding compliance, are weak against the backdrop of an aggression that is blatantly irreconcilable with international law.

Distinct challenges in Gaza

The military operations of Israel in Gaza pose a different challenge for international law. This war has caused almost unimaginable suffering to the civilian population. Currently, conservative estimates put the number of deaths at 50,000, but that is very likely a significant undercount. There isn't a single category of protected or normally civilian object that is still standing in Gaza: hospitals, schools, administrative buildings, libraries, universities, cemeteries, agricultural sites – they have all been systematically destroyed.

© ImageBank4u via Shutterstock

In addition, Gaza has suffered almost 18 months of on-and-off blockade. The coincidence of military operations that have systematically destroyed the means of food production in Gaza, making the population entirely dependent on humanitarian aid from the outside, and this blockade of humanitarian aid is devastating. What we see in Gaza is incompatible with the idea of a war limited by legal constraints. It is incompatible with the notion of restraint that the law commands. Yet, these facts coincide with a forward-leaning, detailed claim of compliance by Israeli officials. Israeli officials consistently argue that not just the war overall but the way in which the war is conducted complies with international law. These claims have been taken up by Israel's allies, chiefly the United States and Germany, and sometimes also by voices in the United Kingdom.

Law’s value in war

This coincidence of unimaginable destruction with the claim of legal compliance, for ordinary people, can only mean one of two things: Either the law is morally bankrupt because it doesn't prohibit this, or the law is useless because the notion that this conduct might be legal is as plausible as the notion that it might be illegal.

© Kipgodi via Shutterstock

In this case, law would simply not fulfill its function of helping us figure out what is right and wrong. I push back against that and argue that law provides the tools for us to evaluate this conflict in real time and that we can, in good faith and with confidence in the best available facts, establish that Israel’s conduct in many cases violates international law.

Compliance with international law

The overall number of deaths or injured civilians or refugees that a particular military operation causes, is not on its own indicative of whether or not a party to the war is complying with international law.

© Frame Stock Footage via Shutterstock

It is one important data point, as is the ratio of civilian to combatant deaths. Ultimately, when we ask whether a party complies with international humanitarian law, we must look attack by attack, because that is where the legal demands attach. Each attack must comply with the principles of distinction, necessity and proportionality. Patterns of attacks matter, but again, as a first indication of whether a party to the war is displaying fidelity to law. To make a determination of whether a particular attack violates international law, we need a lot of detailed information; the law is very fact-hungry. Oftentimes, we need to know what the attacker reasonably thought about an attack, and that is not always easy to infer from the context, which is why it is important to exercise caution. Yet, there is also a point at which we have to say that there are reasonable grounds to believe that there were violations of international law, and those “reasonable grounds to believe” should be enough for third states to take action. Even if we cannot definitively say that a particular attack was a war crime – which is often what people look for in public discourse – the obligation of third states is to demand compliance. They should demand a change in tactics and strategies from the party that is waging war.

Indications of war crimes

The attacks by Hamas and other armed groups on Oct. 7 display clear indications of serious violations of international law, even war crimes. Whether attacks against objects violate international humanitarian law is often hard to determine. However, there are violations of law, even war crimes, that are easier to diagnose from far away. For instance, taking civilians from their homes and bringing them into Gaza for political leverage is hostage taking, a war crime.

© Omri Eliyahu via Shutterstock

Hostage taking is a war crime that was featured on the arrest warrants that the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court sought for three leaders of Hamas – all of whom are deceased by now. It is possible to look at Hamas’ attacks of Oct. 7 and say with a great deal of confidence that not only did they violate international law but they implicated war crimes.

When we look at the conduct of Israel, the International Criminal Court has issued arrest warrants against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former defense minister Yoav Gallant. One of the counts on those arrest warrants is directing attacks against civilians – not that these two individuals themselves attacked civilians, but they criminally failed to prevent such attacks. That means the International Criminal Court has evidence that attacks in Gaza were directed unlawfully against civilians, evidence that at least provides reasonable grounds to believe that war crimes were committed. Besides attacking civilians, the other war crime that looms very large when it comes to Israel's conduct in Gaza is starvation. The combination of attacks against objects that are indispensable for the survival of the civilian population, chiefly food supplies and food production in Gaza, with Israel’s impeding of humanitarian access into the Gaza Strip, has led to what the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification has called an imminent famine. The underlying conduct can amount to the war crime of starvation. It also implicates crimes against humanity. These are the crimes that the International Criminal Court has reasonable grounds to believe Yoav Gallant and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu committed, though arrest warrants are no definitive conclusion that these crimes were in fact committed.

ICC warrant issued

The arrest warrant issued against President Putin was remarkable because it was issued against a sitting head of state. That is still relatively uncommon for the International Criminal Court, though in a sense it is what the court was created to do, because heads of state and heads of government are immune from the jurisdiction of other states’ courts. In some sense this is what we needed an international criminal court for: to close the gap.

© Presidential Press and Information Office via Wikimedia

Genocide with intent

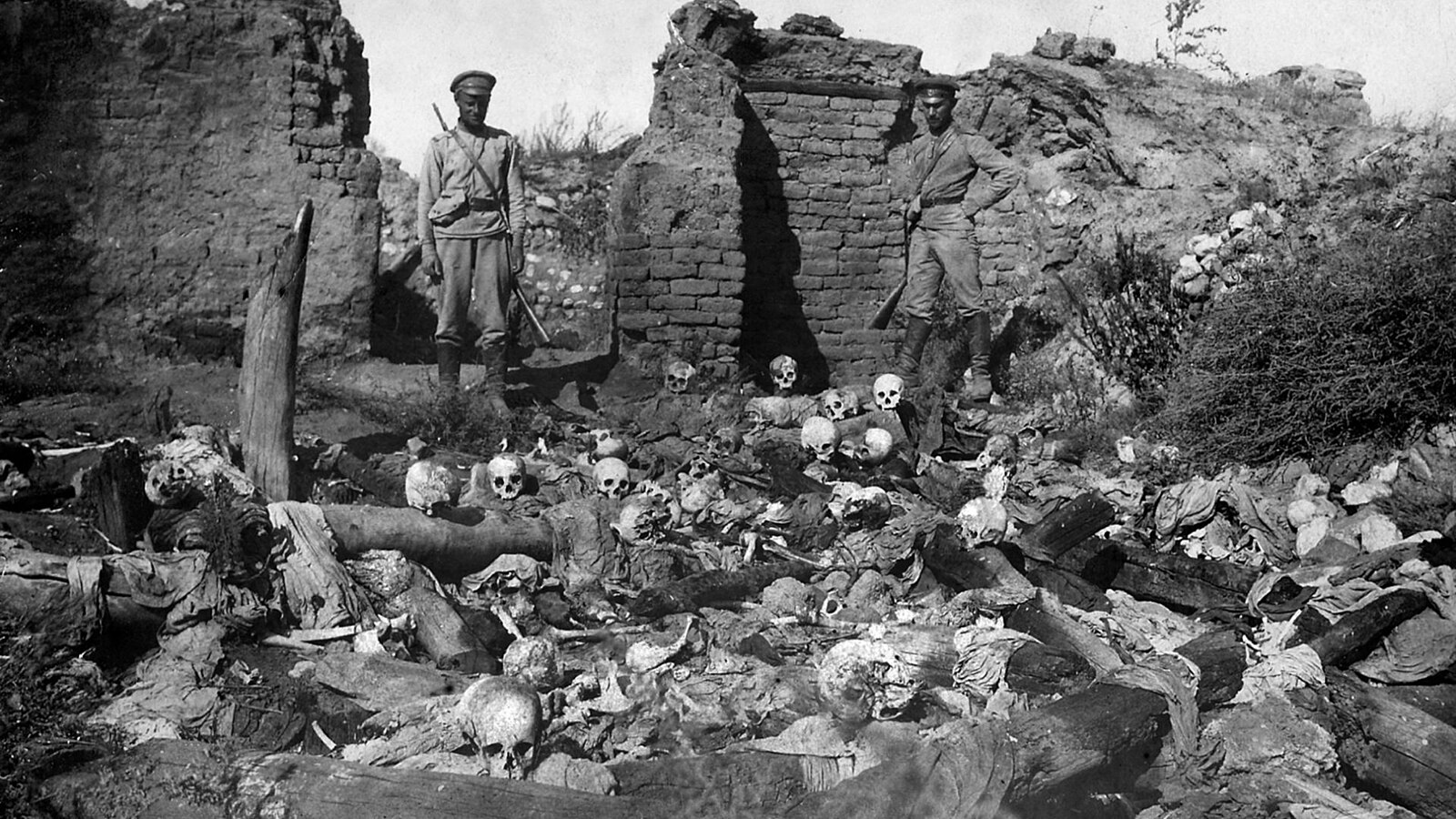

Genocide is unfortunately not an uncommon historical phenomenon: one group of people tries to destroy another group of people in the context of a war or as a campaign of extermination. We call that phenomenon genocide only when we can show that it follows the intent, understood as a purpose, to destroy a group in whole or in part.

© “Album of Refugees”, Tiflis (1917) via Wikimedia

If the extermination of a group is a side effect of a military campaign that follows another purpose, it is foreseen but not intended, then this would legally not be a genocide. Genocide as a legal category is quite narrowly conceived. There is also a high threshold of evidence that we need to meet to show this intent. This obviously carries the risk that allegations of genocide are countered with the argument that there is not enough evidence. The Genocide Convention takes care of this risk by creating an obligation to prevent genocide. The obligation to prevent genocide kicks in at the point where there is a serious risk that genocide is committed. This risk exists when there is a risk that a group will be destroyed in whole or in part, even if there is no clear evidence of genocidal intent yet, because genocidal intent is systematically not visible to the naked eye. So, a risk of group destruction implies a risk of genocide.

Alleviating suffering in war

The most simple and straightforward thing that states right now can and should do is withdraw support from parties to a war that provide reasonable grounds to believe that they are not complying with international law. That is much more effective when you do that toward your allies and friends rather than toward your enemies. Western states, particularly European states and the United States, initially had no problem sanctioning Russia for violations of international law, and they have not, by and large, been able to do the same with Israel. These same states had no problem welcoming the arrest warrant against President Putin and the case against Russia before the International Court of Justice. They have worked with and supported these courts of law, yet they have not been able to do the same in the case against Israel in front of the International Court of Justice, or in the context of the work of the International Criminal Court. Changing that pattern of inconsistency is the most straightforward political prescription that comes out of a systematic analysis of the crisis we currently face. That would make a difference for the people on the ground, because wars can only be waged with weapons, and weapons embargoes can be quite effective in curbing violence.

© Anas-Mohammed via Shutterstock

They also send a message that a state cannot act with impunity, and so they can alter the political discussions within a state. In Israel, for instance, there are different factions that have different visions for how the war and the campaign in Gaza should unfold, and an international community that was steadfastly in support of compliance with international law and that consistently, without fear or favor, sanctioned systematic and severe violations of international law would empower the voices in Israel that demand compliance from the government. It is more complicated in Russia. It is seemingly only President Putin who is making decisions about how the war is conducted. However, the hypocrisy and inconsistency displayed by powerful states like the United States is one of the key problems. Remedying that would alleviate the suffering of people on the ground. Ultimately, people in Gaza not having enough food and Ukrainians in the winter often not having enough electricity to stay warm are outcomes of causal chains that include the delivery of weapons that are then used in violation of international law.

Preventing war by law?

Law on its own is no silver bullet. It can neither prevent war nor make war somehow morally acceptable. The prohibition on the use of force has not saved succeeding generations from the scourge of war as promised in the UN Charter, and even perfectly legally compliant warfare is still a moral catastrophe. Law is only one piece of the puzzle. There are other considerations that must be addressed, like the politics of conflict resolution, long term historical memory and trauma. There are many other considerations that must come into play both to prevent war and to limit those wars that we didn't manage to prevent.

Khmer Rouge victims in Tuol Sleng Prison © Dudva via Wikimedia

The question of what law can do is political. States must stand up for the legal provisions that they themselves wrote and agreed on. The problem of noncompliance with law, and the problem with overly permissive interpretation of law, is one of states not holding each other to account.

Editor’s note: This article has been transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author and edited for clarity. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

wartime laws’ violations

Dill, J. (2014). Legitimate targets? Social construction, international law and US bombing. Cambridge University Press.

Bohrer, Z., Dill, J. & Duffy, H. (2020). Law applicable to armed conflict. Cambridge University Press.

Dill, J. (2015). The 21st-century belligerent’s trilemma. European Journal of International Law, 26.(1), 83–108

Dannenbaum, T. & Dill, J. (2024). International law in Gaza: Belligerent intent and provisional measures. American Journal of International Law, 118(4), 659–683.

Dill, J. (2019). Do attackers have a legal duty of care? Limits to the ‘individualization of war’. International Theory, 11(1), 1–25.

Dill, J., Howlett, M. & Muller-Crepon, C. (2023). At any cost: How Ukrainians think about self-defense against Russia. American Journal of Political Science, 68(4), 1460–1478.

Dill, J. (2018). The rights and obligations of parties to international armed conflicts: From bilateralism but not towards community interest?. In E. Benvenisti & G. Nolte (Eds.), Community interests across international law. Oxford University Press.

United Nations (1951). Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. United Nations.