A clear example would be the major drought that happened in large parts of southern Africa in the early 1990s that had a profound impact on livelihoods and crops in large regions for many months. When you look at it solely from a rainfall perspective, which is what is usually done when thinking about droughts in that part of the world, it doesn’t seem like a very extreme event. The warning systems might have started very late because the weather, from a rainfall point of view, didn’t look exceptionally worrying. However, at the same time, the temperatures during this period of low rainfall were exceptionally high: they were 4°C higher than the long-term average. This led to the soil drying out much quicker than usual. The effects of the low rainfall strongly intensified during the drought, and the impact of the drought was much stronger than it would have been under average temperatures. This is evidence of how even small changes in the likelihood and intensity of extreme events can have a big impact if they lead to different types of extremes happening at the same time.

How climate change affects people

Physicist and Climate Researcher

- Climate change affects people because it changes the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events. Even small changes in the likelihood of extreme events can have a big influence on societies.

- We often think of the impact of climate change as tipping points but actually the dramatic impacts of climate change are the small changes in extremes.

- Different extreme events might happen at the same time. We think of a drought as the lack of rainfall. If it isn’t extreme, but there is an intense heatwave happening at the same time, it will have very strong effects on crops and human health.

- The communities we live in are only adapted to a very stationary climate, the climate we have been used to for many years. Climate change stretches our social systems in a way that doesn’t allow other basic services to be provided.

- We still need to understand which of the losses and damages that happen in society because of extreme weather are due to climate change. It becomes more and more apparent, though, that climate change is already having a very profound impact on lives.

- Weather is an enormous issue in countries like Bangladesh, where villages are flooded frequently and people move into the large cities. What we don’t see at the moment is large-scale or cross-continent migration due to climate change.

Changes in the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events

Essentially, climate change affects people because it changes the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events. Different extreme events might also happen at the same time. These compound events, as we call them, are evidence of how even small changes in the likelihood of extreme events can have a big influence on societies and affect the way we have to deal with and be prepared for extreme weather events.

For example, we might think of a drought as the lack of rainfall – that’s when we record droughts and give out drought warnings. If the lack of rainfall isn’t extreme, but there is a very intense heatwave happening at the same time, it will have very strong effects on crops and human health. However, warning systems might not pick up these events because they are based on weather that we have seen in a colder world.

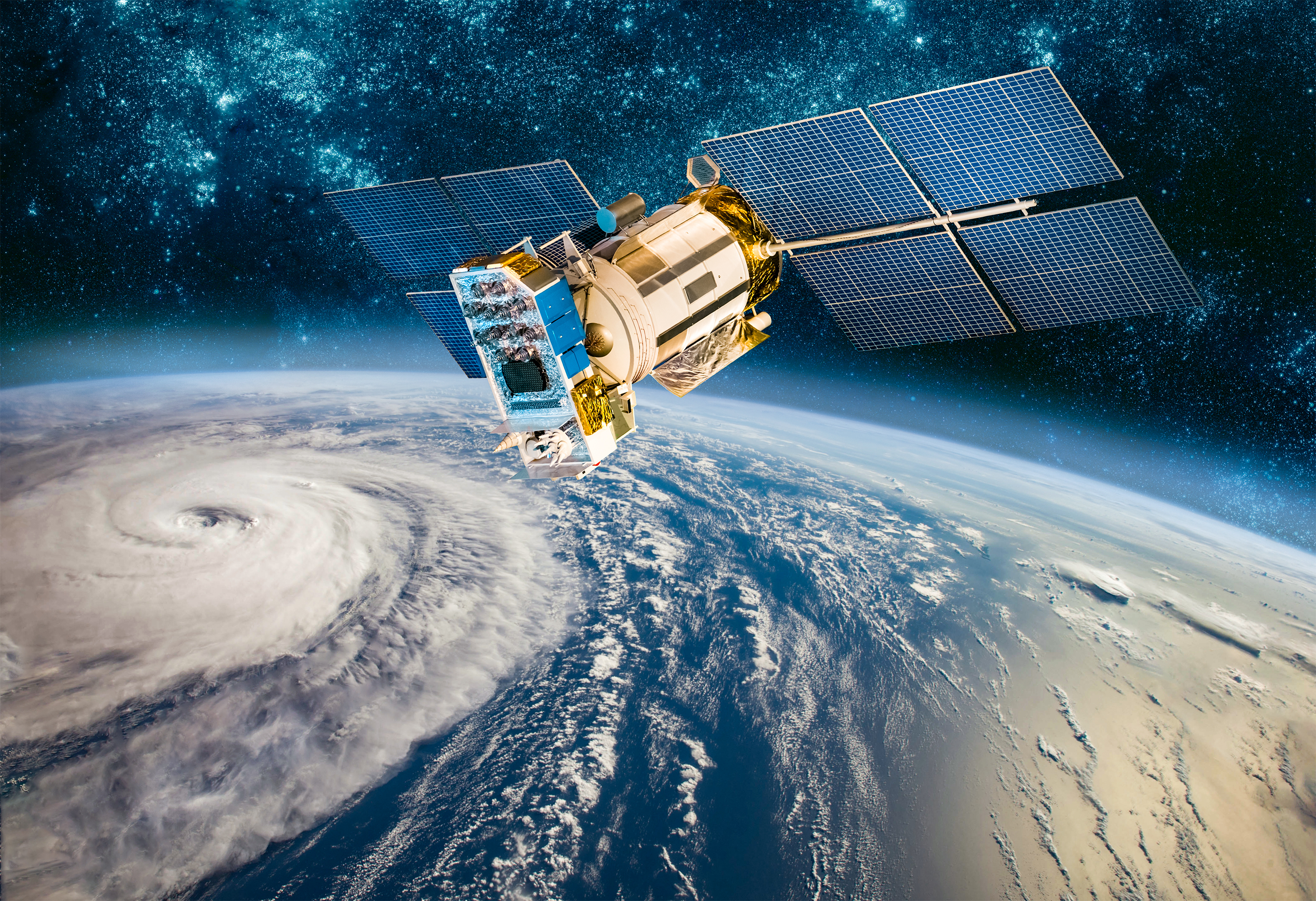

Photo by Riccardo Mayer

Small changes lead to dramatic outcomes

If our social systems are adapted to dealing with drought every five years or so, but you now have the same kind of drought happening every three years, then there is not enough time to recover. As a result, the impact will be more long-term and more profound, even though the change, when you look at the absolute numbers, might not seem catastrophic. This highlights that the communities we live in are only adapted to a very stationary climate, the climate we have been used to for many years. One example is the bushfires in Australia in the summer of 2019 and 2020, in which climate change contributed to making these weather conditions 30% more likely. This doesn’t sound like very much, but we have to think that during the fires, the systems were stretched to the maximum. If the fires had been a bit larger, it would have been impossible to deal with them because there would not have been enough fire-fighters to tackle them.

We often think of the impact of climate change as tipping points – the whole ocean circulation system collapsing, ice sheets collapsing or very dramatic physical events, but actually the dramatic impacts of climate change are the small changes in extremes, because our society is adapted to only a very limited range of possible weather. Of course, if you’re a rich community with many resources, it’s easier to deal with it, so those who pay first are always the communities that are most vulnerable. This also means that the way climate change affects people is not so much that we all die of heatstroke, but that it stretches our social systems in a way that doesn’t allow other basic services to be provided. We are currently seeing that climate change is a multiplier of threats to democracies all over the world.

Measuring the impact of changing extremes on society

Photo by Andrey Armyagov

How we measure the impact of changing extremes on society is a difficult question to answer because at the moment there is no such thing as an inventory of the impact of climate change. We are only beginning to develop the tools necessary to do that now. The kind of research that I’m doing, the attribution of extreme weather events, is one part of the puzzle. We look at which hazards and which extremes have been influenced by climate change, as well as the ones that have been more intense and more frequent, but we are very far from having a global overview. There are a few studies on rainfall events and droughts in different parts of the world, but there are a lot of extreme events that are happening for which we don’t have any assessment of the role of climate change. Some of them are very small-scale events, like hailstorms or wind storms, where it’s very difficult to measure in weather data and also to simulate this in climate models. Additionally, in many parts of the world no assessment has been made yet because of the lack of manpower or the fact that scientists haven’t analysed the climate in that particular region.

Social and economic effects of climate change

This is only one part of the puzzle and one aspect of what we would need to know to understand which of the losses and damages that happen in society because of extreme weather are due to climate change, because then there are economic losses. There are some studies that have combined this attribution work with studies on economic losses after hurricanes. For example, Hurricane Harvey that hit Houston in 2017 in the US caused about 90 billion dollars of damages. Combining this assessment with an attribution study, colleagues of mine have worked out that about 6 to 7 billion dollars of these 90 billion can be attributed to the changing risk in the extreme rainfall that occurred accompanying Hurricane Harvey.

But these are not the only effects that climate change has on society. On the heatwave side, there are health impacts and mortality rates which can be measured, but in many parts of the world, this is not something that is assessed. We have no data basis to know what deaths are attributable to climate change. There are also some studies looking at mental health effects after flooding, for example. All these effects are hugely important and influence livelihoods. We have data on some regions that can now be combined with the climate science assessment and give estimates on individual places, but we don’t have a global overview. It becomes more and more apparent, though, by piecing all these puzzle bits together, that climate change is already having a very profound impact on lives even in today’s one-degree world, and that is despite the climate changing very much exactly in the way that was predicted decades ago. All these changes happen in a very predictable way, but we just haven’t prepared for them.

The creation of climate migrants?

Photo by Catay

One of the impacts of climate change that is often talked about in the media is climate migrants, and climate migrants are a very good example of the difficulty of piecing together these evidence puzzles that we have from different kinds of research. Migration is always multi-causal. People migrate for all sorts of different reasons. One reason might be that the weather in the region of their origin is adverse to their livelihoods. In parts of eastern Africa, this has always been part of life. Thus, mobility across the whole region because of the weather is nothing new.

This type of migration happens very much within the region or within the country and people return. But of course, if the situation changes more than in natural climate change, it could be that people are not able to go back or people have to go further away. And so this can then, of course, be a reason for people migrating out of the region that they have historically migrated in. However, at this point in time, there’s very little evidence that we are seeing people migrating because of climate change.

Looking for evidence of large-scale migration

We know that weather is an enormous issue in countries like Bangladesh, where villages are flooded frequently and people move into the large cities, making them very crowded. There are regional examples that migration because of the weather is increasing, but what we don’t see at the moment is large-scale or cross-continent migration. This doesn’t mean that it is not happening; it means that evidence of why people move and where people move is difficult to collect, and it’s done mainly in social science studies that are very localised. To fit this kind of data with climate scientific assessments, which are almost always on large regions and over longer timescales, we have to be able to answer the questions: do we have climate migrants already? How many, where and how will that change in the future? We need to merge these two very different ways of doing science to find an overarching way of answering these questions before we can give any reliable numbers.

Discover more about

Reponding to extreme weather

Otto, F. (2019). Attribution of extreme weather events: how does climate change affect weather?. Weather, 74(9), 325–326.

Stott, P., Christidis, N., Otto, F., et al. (2016). Attribution of extreme weather and climate-related events. WIREs Climate Change, 7(1), 23–41.

Otto, F. & Harrington, L. (2020, September 13). Why Africa’s heatwaves are a forgotten impact of climate change [Guest post]. Carbon Brief.