Touch is the one sense that completely defeats the powers of representation, because you can reproduce sight with a camera – you can now see me on screen – or sound, or even smell can be simulated. Touch dies with the person, as if life hovered on the corpuscles of our skin. Literature struggles through metaphors, images and narrative structures to communicate this most intimate and almost evanescent of the senses.

Touch and intimacy

Professor of Modern Literature and Culture

- Touch is the most intimate yet least representable sense, and when language falters the body speaks, especially through the hands.

- It is one of the ironies of the First World War that it brutalized the male body on an unprecedented scale. At the same time, it also restored tenderness to touch in everyday life.

- Touch was the most intimate frontier along which empire was policed. In WWI, soldiers of color were not allowed to touch white officers.

- AIDS and COVID showed how essential non-erotic touch is for comfort, grief and solidarity, and how its absence wounds private and public life.

The most intimate sense

Touch is the most intimate and the most elusive of the senses. Is it one sense or a group of senses?

© Santanu Das, personal archives

Language and touch

Albert Camus, writing in the middle of war, said that the artist is freedom's witness, for it testifies not to the law but to the body. Later, in a different context, Roland Barthes, one of the greatest philosophers and critical thinkers of the 20th century, said that language is like a skin. It is as if I have words instead of fingers. My language trembles with desire. Often, in times of crisis, the body moves in to fill the gap left by language. At the same time, we can think of letters as words addressed to the absent body. There is a very intimate relationship between language and this most intimate of our senses.

What hands convey

The hands remain some of the most intimate and conscious points of our contact with the surrounding world. For example, Heidegger has this wonderful passage on the hand where he says that the hand creates. The hand gives. In many ways, what makes us human and differentiates us from animals is the versatility of our hands.

© Regiane Tosatti via Pexels.

When you see a friend who is in distress or even dying, we go and pat, touch or stroke that friend rather than trying to speak to them. The body fills in the gap left by language, and it is the hand that often does most of this action.

The brutalization of the body

The wonderful modernist writer and artist David Jones once said: "Art insists on one thing. It insists on the infantryman's job. It insists on the tactile." I guess we realize that particularly in the First World War, because there the visual geography of everyday life was replaced by the tactile world of the trenches. Men would navigate distance not through the verticality of our body but often through the horizontality of the beast. The words that come up, the verbs that come up in the trench narratives are creep, worm, crawl, because this is how they would often move across the trenches. On one hand, there is this brutalization of the body during the First World War – they are wading through what I call slime scapes, this octopus of sucking clay, as Wilfred Owen once said.

Soldiers in Trench World War I © Italian army.

After three weeks at the front, Wilfred Owen writes to his mother: "I have not seen any dead. I have done worse. In the dank air, I have perceived it, and in the darkness, felt." Touch becomes, for Owen, the ground of both testimony and trauma.

It is one of the ironies of the First World War that it brutalized the male body on an unprecedented scale. At the same time, it also restored tenderness to touch in everyday life. For example, the men would often bathe together. They would nurse each other when one was ill. They would often hold hands and dance together, and at night, their bodies spooned together.

Kissed him twice

This is a letter from Lance Corporal Fenton to the mother of a close friend, Jim, who had just been killed. He is writing to the mother: "I suddenly saw Jim reel to the left and fall with a choking sob. I did what I could for him, but its stout heart had already almost ceased to beat, and that must have been instantaneous. Yes, I held him in my arms to the end, and when his soul had departed, I kissed him twice. Where I knew you would have kissed him on the brow – once for his mother and once for myself."

These are singular moments of intimacy and intensity. Vulnerability, a sense of impending death and mutilation, bereavement and the diffuse eroticism – sexuality had not yet hijacked a more intimate history of emotions. There is a certain almost radical innocence about letters such as these.

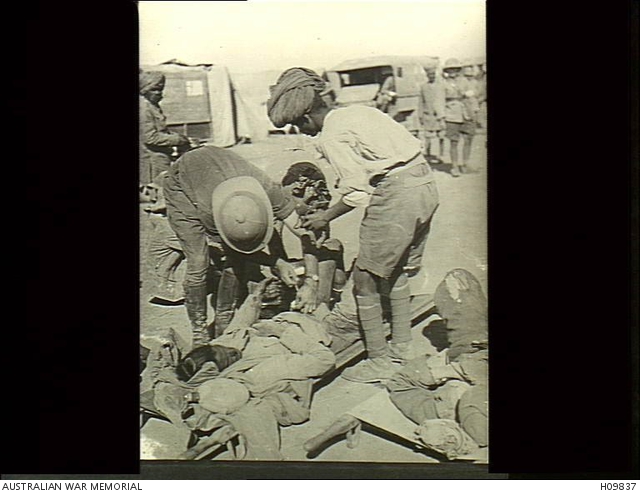

British and Indian Army medical staff at an advanced dressing station attending to a wounded soldier, Mesopotamia. c. 1918 © Australian War Memorial.

The writing of the First World War almost obsessively circles around these moments of touch and intimacy, from Rupert Brooke's "linked beauty of bodies" to "the full nerved still warm". Here I am, quoting limbs of the dying boy in Wilfred Owen's poems, or Siegfried Sassoon's "my fingers touch his face," to Robert Nichols's more sentimental "My Comrade," "that you could rest your tired body on mine." Even in First World War plays, there are always hugs and pats and caresses between men.

Perilous intimacy

Wilfred Owen is the central protagonist in this drama of touch and intimacy, and just a few weeks before his death, he writes to Siegfried Sassoon about his servant: "Jones, shot to the head, who lay on top of me, soaking my shoulder for half an hour." He continues: "Catalogue. Photograph. Can you photograph the crimson hot iron as it cools from smelting? This is what Jones's blood looked like and felt like. My senses are charred." What we have here is this moment of perilous intimacy – vulnerability, a certain visceral thrill, loneliness, affection – they are all fused and confused. It is a moment of non-genital tactile tenderness at a moment of extreme violence, and this is where we see some of the war writings at their most intense.

Affection and care

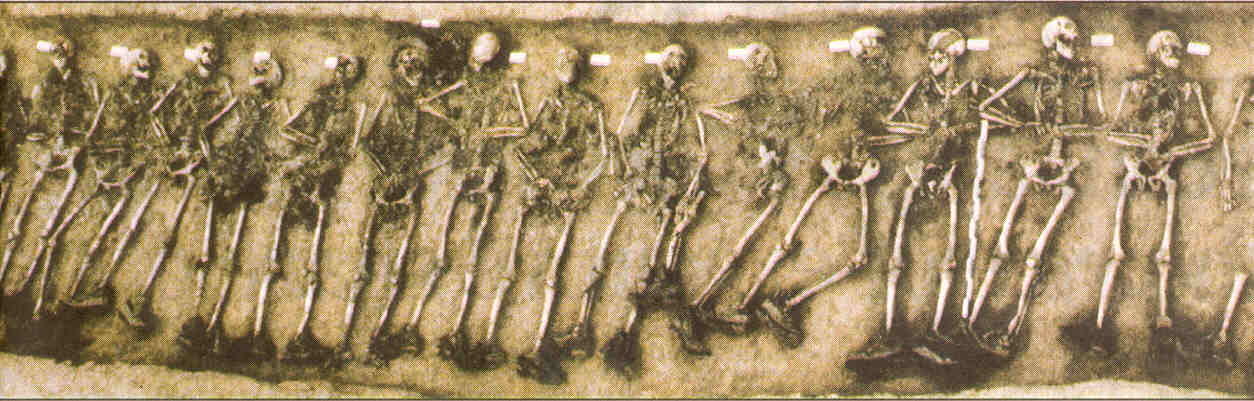

On the 21st of May, 2001, there was this extraordinary discovery by a team of French archaeologists of this mass grave near Arras in northern France; they found 11 bodies buried, and then one more just next to them at a slight distance, joined arm in arm. I do not think there has ever been discovery of a group burial like that. The conjecture is that they were all privates, and the officer was slightly separate. Again, we do not know. What is remarkable is that, when I look at it, I almost see the traces or shadows of these other hands who must have arranged the hands of the dead soldiers under fire as a testimony to their friendship.

10th (Service) Battalion, The Lincolnshire Regiment, nicknamed the Grimsby Chums © Santanu Das, personal archives.

The affection and the care that must have gone into the process to arrange them like that is very moving – one of the most moving tributes to this whole idea of camaraderie, but equally telling is this slight distance between the men and the officer.

Lines of color

Touch, being the most intimate of the senses, was also the most intimate frontier along which empire was policed. For example, in the First World War, there was this huge scandal, because this white nurse was touching the shoulder of this Indian soldier.

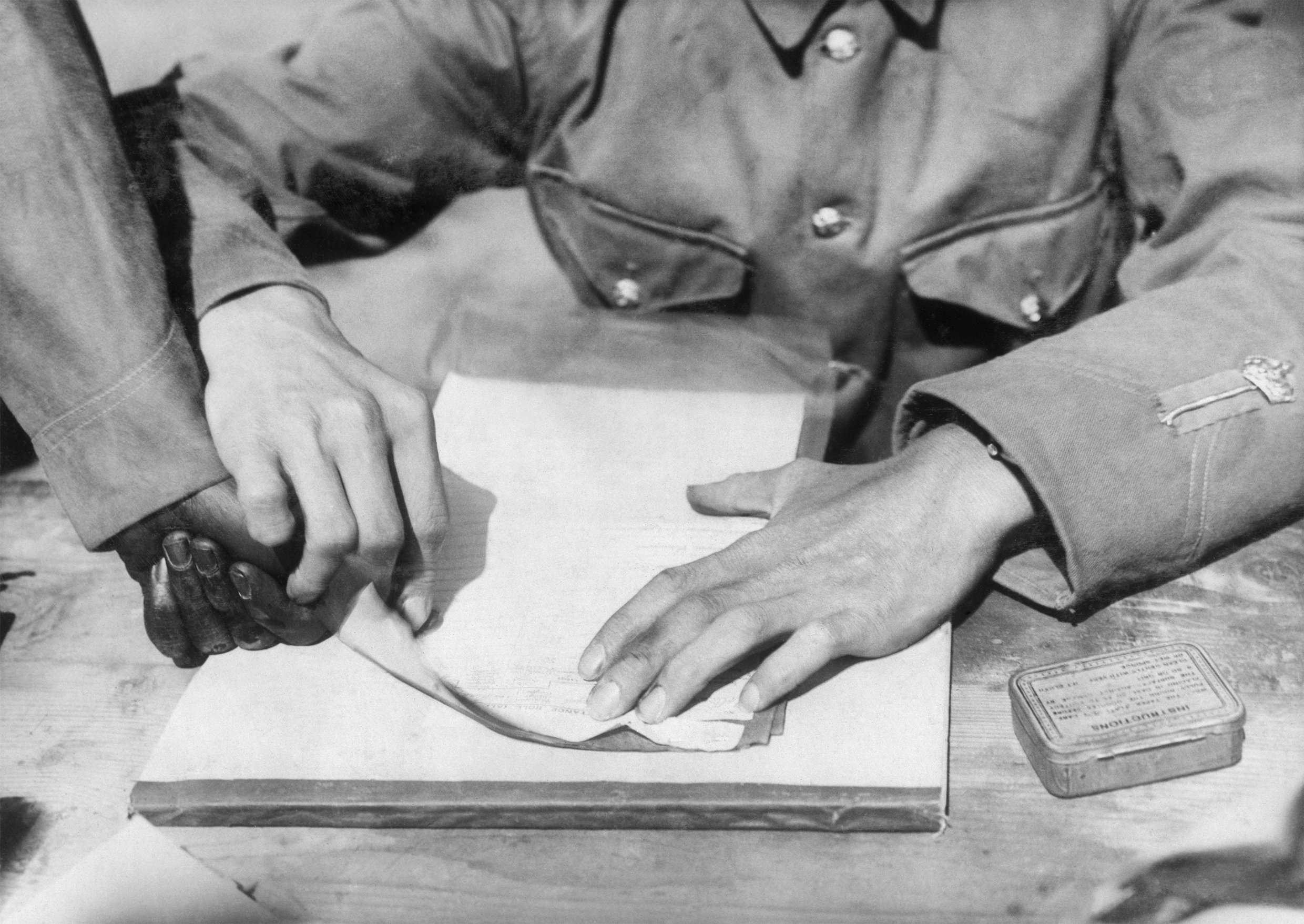

One of the most striking examples of touch along the lines of color is that of two hands that we see. We do not have any names or faces.

A soldier, unable to write, gives his thumb-impression on the pay-book © Santanu Das, personal archives.

We see this white hand, uniformed, quite assertive, as you can see in this photograph, guiding this black or colored hand to put a thumb impression. You realize this is the stamp for recruitment, and this is how most of these soldiers of color were recruited. I think the whole hand had been dipped into an ink pot to get this impression. This is one of the most impersonal examples of touch, compared to another picture, where there is this badly wounded or injured Indian soldier in a wheelchair.

Wounded Indian troops at a hospital in Brighton, August 1915 © Imperial War Museums (Q53887).

He is dictating a letter to the Indian scribe, but also leaning across to touch the shoulder to say, thank you, my friend, for writing the letter for me. These are two very interesting examples – one across the line of color, impersonal, almost savage, and the other full of tenderness.

Make peace with the dead

One is reminded of one of the key moments during the AIDS epidemic. That is the photograph of 32-year-old David Kirby, the AIDS activist, as he lay dying. He is comforted by his father. A couple of feet away, there is his aunt comforting her daughter. The carer is seated on the other side. It is almost like the modern Pieta.

Michelangelo's Pietà in St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican © Vatican Museums via Wikimedia.

I am reminded of a few lines from one of the poems by Thom Gunn: "And you perceived that he had to be comforted. You climbed in there beside me and hugged him, plain in view, though you were sick enough and had your own fears, too." This is exactly what Covid had deprived us of: these little hugs, pats and caresses by which we reach out and connect to people.

During COVID-19, those 2 meters or 6 feet determined for many of us not just how we responded or reached out to the living or failed to but also how we continue to make peace with the dead – because we were not allowed to visit them, to touch them.

At a personal level, I remember going to a concert for the first time after the pandemic, and it was an overwhelming experience of being with other people in the same space. Suddenly we realize how absolutely even touching at a distance is important to the functioning of our everyday lives.

Moments of crisis

W.H. Auden in The Age of Anxiety said that in moments of crisis, even the smallest expression of affection takes on a profound dimension. During war – the First World War, Second World War…we are living at the moment through several wars – we have these pictures of people absolutely ravaged, destitute, dying, yet there are moments of touch and intimacy.

World War I, a hospital in Antwerp, Belgium, ca. 1918. © Shutterstock.

Covid was very different. There was not this brutalization by industrial weaponry. There was this invisible thing, but there also could not be this sense of touch and intimacy, which is so needed in these moments of crisis.

A world of hugs

The problem with touch is that sexuality has hijacked the history of emotions, and it is very difficult, but also very important, for us to carve out a space for non-erotic touch – this world of hugs, pats and caresses that we are gradually losing in this excessively sanitized culture. Perhaps it is for a good reason, but I think it has its own dangers.

© Santanu Das, personal archives

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

the power of touch

Das, S. (2006). Touch and Intimacy in First World War Literature. Cambridge University Press.

Das, S. (2023). Touching Wounds: Violence and the Art of “Feeling". In A. Kern-Stähler & E. Robertson (Eds.), Literature and the Senses (pp. 414–431). Oxford University Press.

Das, S. (2007). War Poetry and the Realm of the Senses: Owen and Rosenberg. In T. Kendall (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of British and Irish War Poetry (pp. 73–99). Oxford University Press.

Das, S. (2016). The Theatre of Hands: Writing the First World War. In Marcus, L., Mendelssohn, M. & Shepherd-Barr, K. E. (Eds.), Late Victorian into Modern (pp. 379–397). Oxford University Press.

Das, S. (2020). Touch and Intimacy in the time of Covid 19. Fifteen Eighty Four, the blog of Cambridge University Press.

Owen, W. (edited by Stallworthy, J.) (2018). The War Poems of Wilfred Owen. Vintage Classics.

Auden W.H. (1947). The Age of Anxiety: A Baroque Eclogue. Princeton University Press.