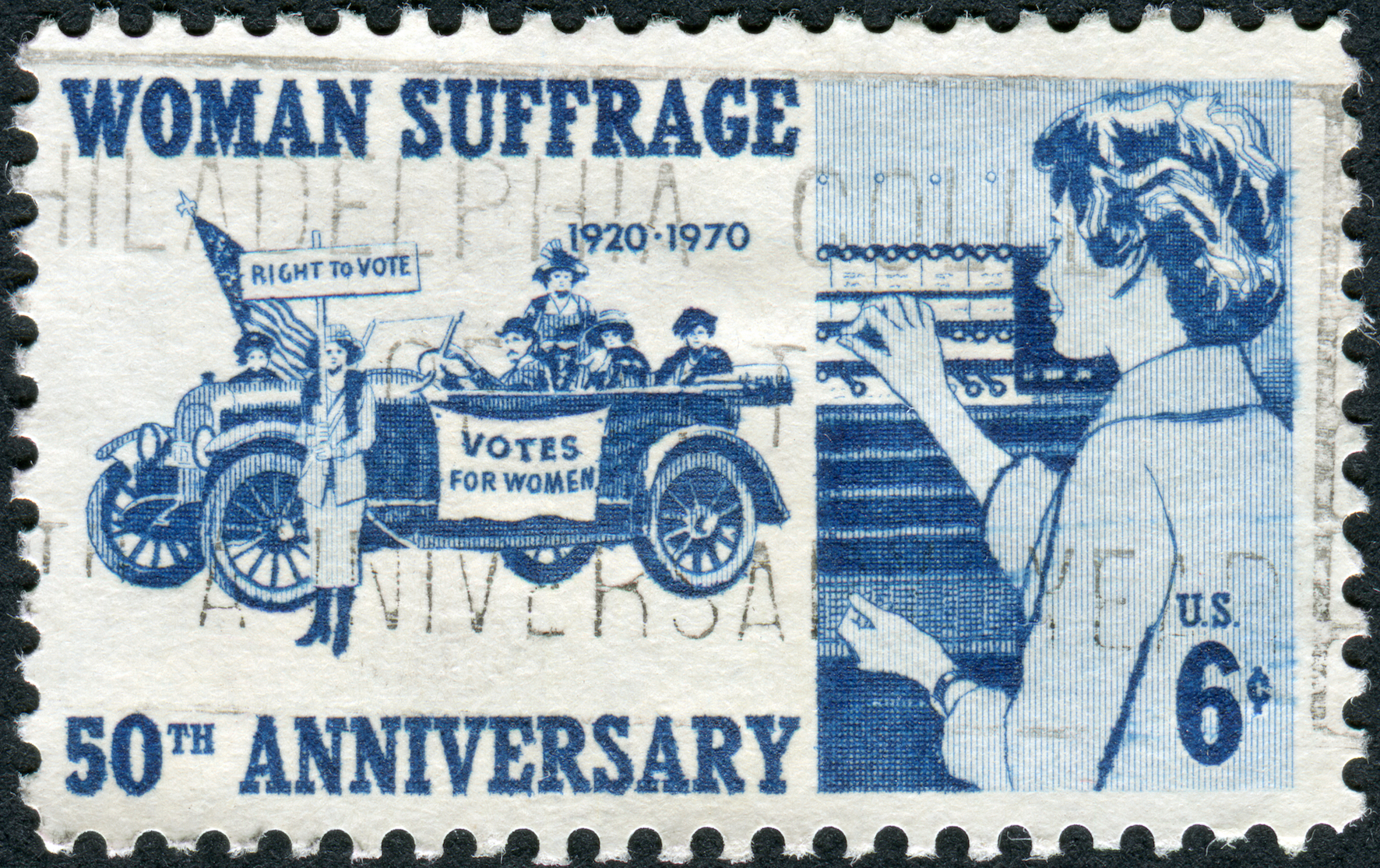

Citizenship has different meanings. It means voting, and participating in the political and the public sphere. In international law, it also means the link almost every human being has to a nation state. This link has been developed and created differently, depending on different stages of history.

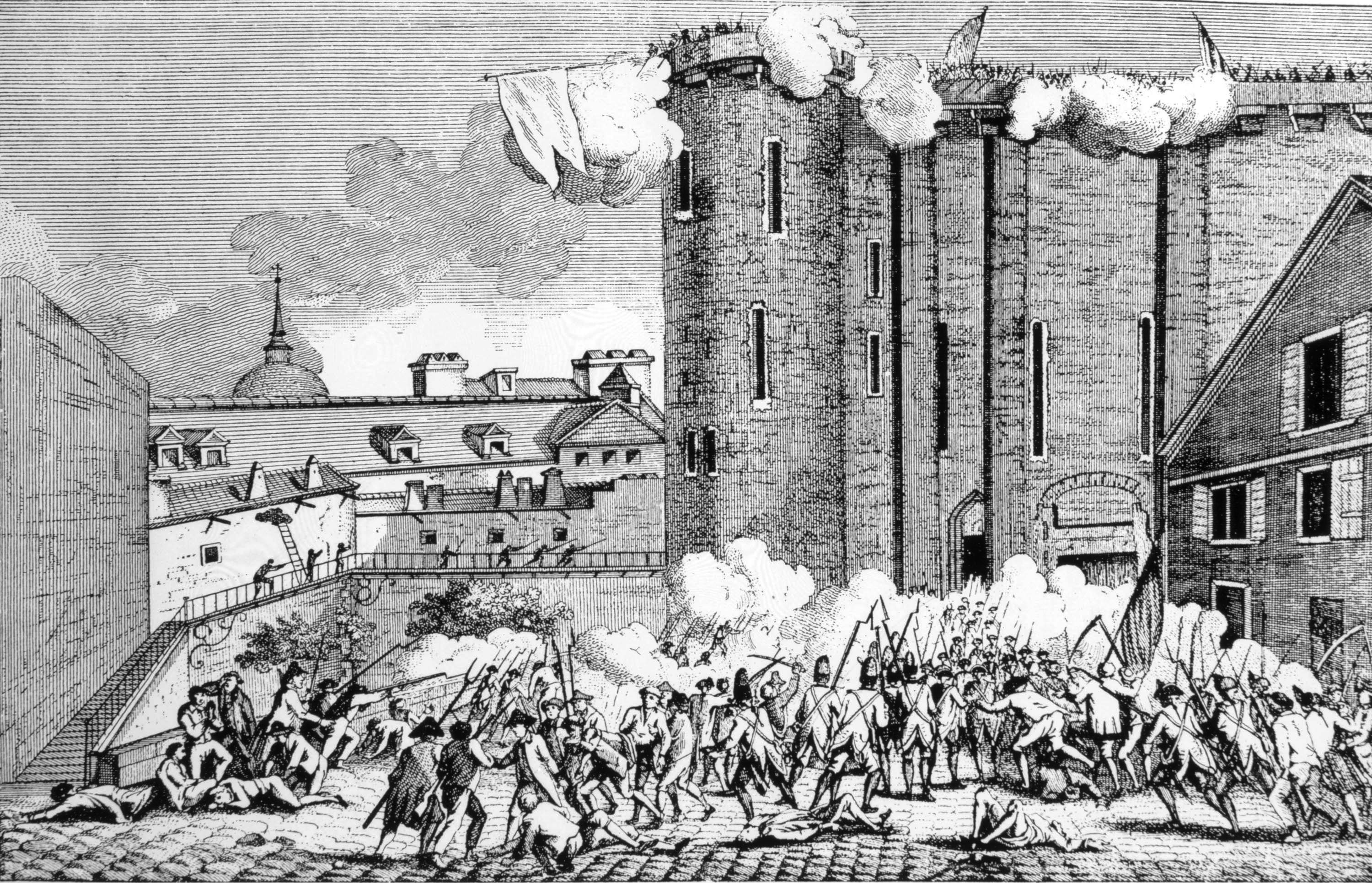

Before the French Revolution, the human being’s link to the State was their place of residence. People living in the territory of a king had allegiance to him, and that determined the link to nationality or citizenship. The French Revolution transformed this link because the nation became the body to which a human being was associated. But it went further. Before the French Revolution, in the whole of Europe, the main feature that associated a human being to a State was place of birth. If you were born on the territory of a king and still resided on this territory, you had allegiance to the king and you could be defined as a subject of the kingdom.