Human rights are essential for all humans. After women, children might be thought of as the last phase of Enlightenment thinking in terms of getting their rights recognised. It takes time for rights identified in any treaty to take hold in any society.

The United Nations launched the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) in 1989 after a ten-year drafting process. Countries all over the world rapidly ratified it and it became the most universally ratified treaty in history. Ironically, I’m saying this from New York, in the only country that has not ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The CRC contains articles on provision and protection, as you would expect. Additionally, it includes articles on participation, on the rights of children to be actively participating in society, to have a voice, to have information and to be able to gather collectively. The treaty had a powerful effect. When the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child began to meet, the secretary was shocked to see how much children themselves had become the powerful agents of change. Having a voice turned out to be an excellent motor for the achievement of children’s rights. Children started to change the way some cultures viewed childhood, how adults saw children, as well as how children saw themselves as citizens with rights. It was a radical change.

The effects of the UN Convention

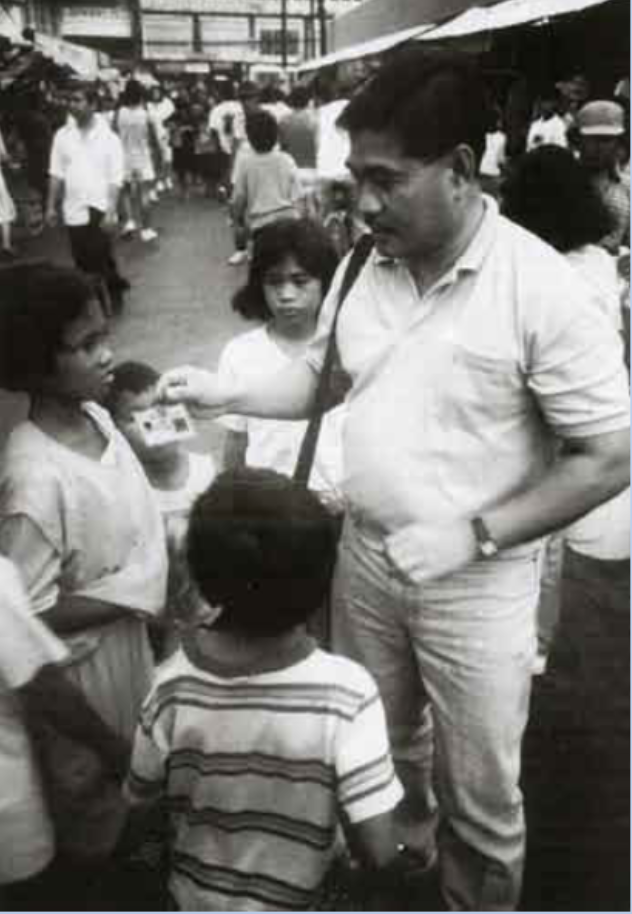

After the CRC was ratified, I was privileged to be asked to travel to some countries to document how children were beginning to hear about and act on their rights. Brazil and the Philippines were particularly valuable for me to visit because the launch of the UN CRC coincided with the emergence of these countries from dictatorships, so children were now championing many of the rights that people had been waiting for and they became the vanguard of human rights talk.

It was remarkable to learn that many of the children who lived, or worked in, the streets in these countries were beginning to see themselves in a different light. They no longer thought of themselves at the bottom of the social ladder, but as citizens like everybody else, and they felt that they had a right to talk about their rights. I have since witnessed instances of this revolutionary change in consciousness all over the world that can happen when children learn about their rights.

There are two aspects as to why children’s rights are essential. First, it enables us to articulate policy, law and legislation to protect and to provide for children. Also, it recognises that children are not merely citizens in waiting, but citizens from birth who can gradually exercise citizen rights, according to their developing capacities.

Not everyone is aware of this radical change. It’s ironic that I have to work in the United States, a country that doesn’t recognise children’s rights. Most people in the USA have never even heard of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Criticism of the CRC

Quite a few scholars did not accept the Convention as it was; they felt it was too Eurocentric, stressing individual liberty, another example of the West broadcasting its values upon other world countries. I disagree with the cultural relativist idea that we can’t expect there to be universal rights for children but I do think of course that the CRC must be interpreted within a cultural context. I believe that the UN Committee on the Rights of the Children, in Geneva, that monitors and reports on the implementation of the CRC, is cognizant of cultural context as it progressively interprets the treaty in its regular review of all national CRC reports of progress. Furthermore, the CRC is clear in emphasizing that it is parents who are the primary managers of their children’s rights through their different customs but the focus on the individual child and their individual rights to protection, provision and participation is also fundamental.

Savitri Goonesekere, a highly respected Sri Lankan lawyer, has written convincingly of the importance of the CRC in South Asia. It has been invaluable to lawyers in enabling them to safeguard children from harm and early marriage, and to help protect the many children who are sent away from their family homes to be domestic workers, where they often suffered from workplace abuse. All these cases became easier for lawyers to begin to deal with once they had an official document stating that children had the rights to protection as well as to the provision of services, adequate housing and a family environment.

In the early years after the ratification of the CRC, I travelled to a number of countries to see what was happening in terms of their participation rights. During these visits, I met many street children: the working children who are the most noticeable to tourists. They were already confident children, but now they carried a different kind of confidence; they saw themselves as rights holders and were empowered to speak about it and even formed associations with the support of adults.

Adult streetworkers, who were child rights advocates, were then able to help the street children organise in deeply democratic ways so that the children could start to have a voice. The children honed their organising so well that I observed children competently running meetings by themselves. In these local meetings, the street children made plans for change within their daily lives, trying to work on how to manage accounts for the money they earned and generate projects to improve conditions for themselves and their peers. From these local meetings, the street children elected representatives to go to city-level meetings and, in the year that I visited, there was a national congress of street children that resulted in a presentation of proposed policy changes to the government.

Thinking creatively

It’s important to recognise that there isn’t just one way to communicate. For young children to have a voice, you have to think creatively about their communication abilities. In the Philippines, during the dictatorship the streetworkers were trained in community political theatre, and they used this skill effectively to train the children. When the children wanted to communicate a complex rights issue, they would act it out. For example, they might perform a drama about a domestic struggle and family violence. Two or three children would get up and perform it, and the rest of the children would critique it and ask questions while another child would be on the side making concluding notes regarding this particular problem and how to solve it. I observed that process closely for a couple of days and was amazed by how they came up with new ideas that nobody else was talking about that were pertinent to their lives.

One of the scenes particularly impressed me because it wasn’t specifically about children. It was about the elderly. The children acknowledged the issue that older people had of getting up in the middle of the night and taking the wrong pills because their medicine was mislabelled. These poor older people suffered because they couldn’t buy pills in small quantities and so they bought a few unlabelled pills at a time. The children were able to recognize this small, every day event as a human rights issue for other members of their families. Children were elected to present this to the Congress of the Philippines as a way to seek change, along with a couple of other changes that they wanted to see turned into national law. The change prevailed due to the careful thinking the children had put into their presentation.

While street children got a lot of recognition in the early years after the launch of the CTC, they were an easy group to work with. Firstly, they were accessible on the street. Secondly, in many countries, “street workers” had found them in the street and had been reaching out to them for years. These children were not controlled by a family or employer and were able to work with the street workers on their rights. However, street children aren’t the only example of children who benefitted from the CRC’s protections. Many more children do dangerous and harmful jobs such as making fireworks in factories or helping to build highways.

We periodically hear about disasters related to child labour and hazardous work environments like the firework factories. Embarrassingly, we also know that children often manufacture the clothes we wear and the soccer balls we kick in the West. Although children’s rights are recognised, awareness of these rights in the United States is often tied to the increased price of products, owing to the influence of the CRC in improving conditions for children. Yet, the perverse problem of underpaid child labour, like girl garment workers in Bangladesh, was only officially acknowledged by the United States Congress in 1993 when Senator Harkin introduced a bill. However, the bill created unintended consequences.

After the US Senate passed Harkin’s Bill, the garment factories dismissed many Bangladeshi girl labourers. Following the legislation, the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association, in collaboration with UNICEF, established factory inspections. They went to factories to check and make sure children weren’t working. There was no plan for what the children would do if they weren’t working in the factories, or how their households would make up the lost income. The Bill was not designed holistically, and it had not considered its impact on families because nobody had talked to the families. Most of the children began working in much more deplorable situations, such as scavenging through trash and begging on the streets. Many girls ended up in prostitution. In the end, a plan was developed, with UNICEF, to pay financial compensation to the families and to provide schooling very close to their homes in Bangladesh so that they could improve their children’s opportunities to get a good job with a fair wage later on. However, the case of the Bangladeshi anti-child labour movement and Harkin’s Bill proved to be a painful struggle and demonstrative of the dangers of trying to promote children’s rights from the outside rather than from within, considering local customs, and the perspectives of parents and children.

The efforts of international organisations

Over the years there have been many efforts by people in international organisations, to improve children’s working conditions. However, we only started to see a change once children began to participate in the dialogue.

During a series of contentious international conferences on child labor, beginning in the 1990’s, organized by the International Labor Organization (ILO), children argued for their right to work and go to school, expressing this sentiment: ‘Talk to us about what we want. We can’t give up our jobs because we have to support our families; instead, talk to us about what kind of work we accept and what we don’t accept, and how we can have an education as well as a job. Working children have become increasingly involved in the child labour rights movement. They have learned how to self-organise democratically with the help of powerful child rights advocates who promote participatory democracy and teach the children how to run their meetings. There are now thousands of working children organising all over the world struggling to change their local conditions, but progress is slow.

Knowing their rights

People often wonder how children can know their full rights when the treaty is a long and complicated document with many articles. There is more than one answer to this query. Activists have made an effort to simplify the CRC’s language into child-appropriate vocabulary that is not so legalistic. Often, the CRC’s principles are pictorially articulated. However, the critical point to make is that we can’t just select a few rights and say, ‘These are the ones you should know; the other ones aren’t as important.’ All the rights are essential and work together in complex ways but children need to know that they have protection rights, provision rights and participation rights. They should understand that they have a right to protection from harm, the provision of adequate services and support and the rights to participation.

The participation articles include Article 12 of the CTC that gives a child the right to have a voice on all matters that concern them according to their capacity, which means their developmental age. Additionally, Article 13, on the right to information, maintains that minors must have access to all information they need to exercise their full right of freedom of speech. Children can’t be refused information. Also, children now have a basic right to come together and organize in associations like the Filipino street children described in this essay. The inclusion of these articles on participation encourages children to speak out and to form associations that can then serve as a place where they can better articulate their needs and considerations, which include those for their families, for themselves and for their communities.