Market design is the application of rigorous economic theory to redesigning real-world market institutions. When most people think about markets, they think about going to a supermarket to buy an apple. Yet, markets are often much more complicated. In particular, some markets don’t emerge organically but instead need a bit of engineering. Market designers try to create rules and infrastructure for markets to function effectively.

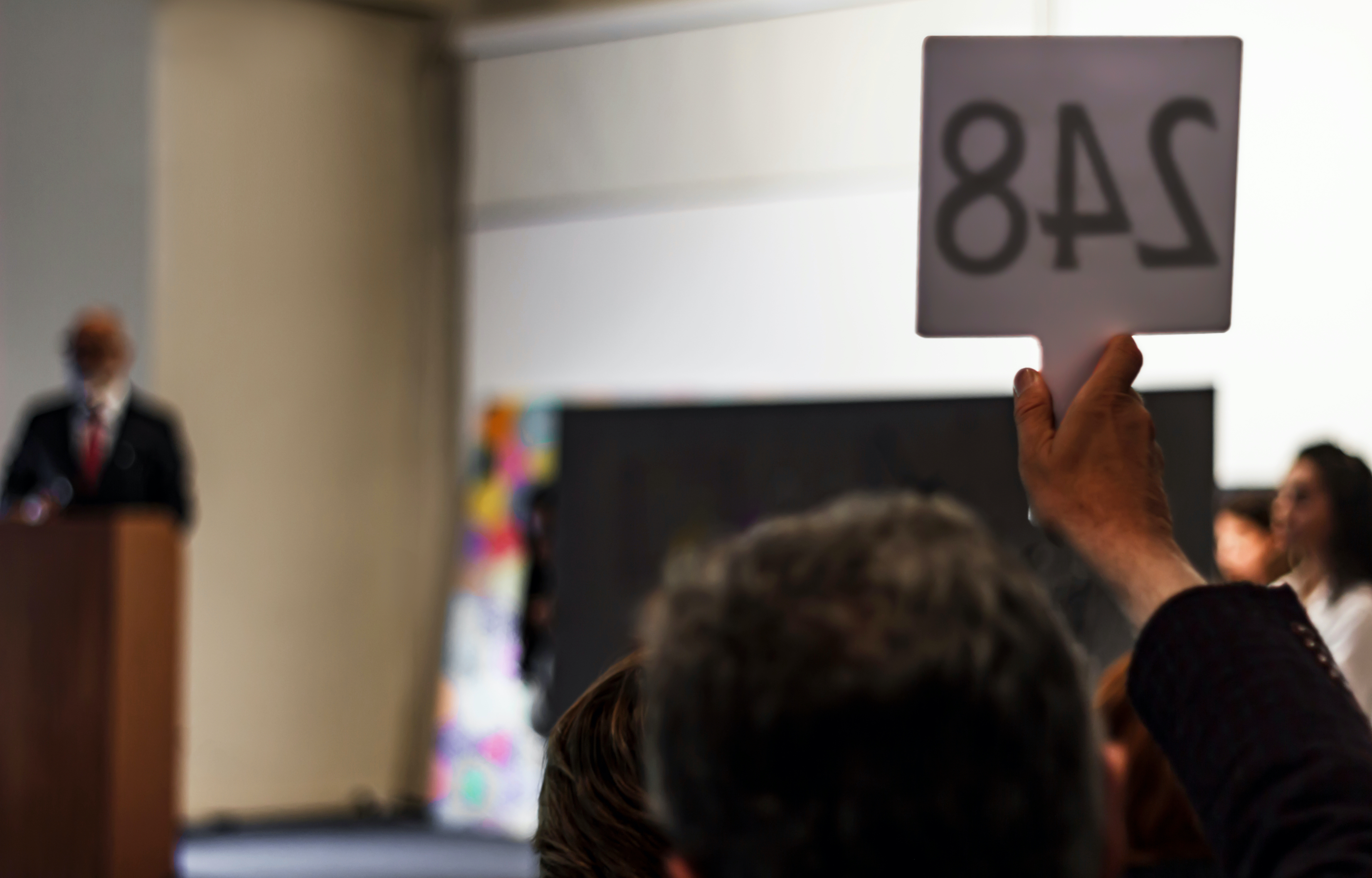

A simple example of a designed market is an auction. If you were to buy an expensive painting, you might find yourself in an auction house, and there are rules about how the auction works. For instance, the painting might go to the person who bids the highest amount. Indeed, this is a type of market, but it’s been carefully designed to fulfill the objectives of the person selling the painting or the auction house and its participants.