We and the other

There’s a huge and difficult problem at the heart of this subject called anthropology, which is the intellectual discipline where we describe, analyse and evaluate the ways of life of ‘others’. Anthropology became the science that centred on our understanding of other peoples. The problem is all to do with who we are and who are those whom we study.

The scholars who were the early anthropologists, or social scientists, resolved that they could describe or discover humanity by looking at others. But who were the we and who were the others?

In the history of science, from the 17th through to the early 20th century, we have been white men – usually Christians – nearly always living in powerful imperial societies. The others have been the peoples who were somehow deemed, by the very assumptions we made, by the intellectual models we carried with and within us, to be lesser and inferior.

There is always, in early anthropology, in thinking about humanity in the premodern period, the idea that all humans are or have been on an evolutionary journey. According to this view, we – the white Christian men living in imperial and powerful societies – sit at the top of the ladder. Since this ladder leads from the ‘primitive’ and ‘savage’ up to the heights of European civilisation, we, who are both scientists and members of civilised societies, are the most sophisticated human achievement. Other people are further down, on rungs of the ladder somewhere below us. And those others might be women, they might be the urban poor – but they are typically, in the history of anthropology, the dark skinned and tribal populations that have been encountered as a result of imperial conquest. This evolutionary model, this construction of the other, is inseparable from imperialism.

The imperial project is to go to someone else's land and take from them all that they have, or all they have that we think we could use or profit from, including the people themselves. To establish our entitlement to this invasion and expropriation, we must insist that they, the people we encounter in these new lands, have no rights – be it to their land, their cultural traditions or even to life itself.

In so far as anthropology has emerged from this imperialism, it is rooted in an extremely uncomfortable intellectual and political narrative – a flow of events and stories about other people in which the ‘savages’ are consigned to a position where they cannot claim that which is their own. In this narrative, we, the powerful white males, can take what we want – it might be their land; it might be their language; it might be their bodies – and we can justify this if we can prove that these other people, these people lower down the ladder, are in need of development in order to become fuller, better, more evolved human beings. Thus, it is implied, or, often enough, baldly stated: conquest and dispossession are in the interests of the conquered and the dispossessed.

Thus, the representatives of European empires – especially of Spain and Britain – justified their occupation of other people's lands, their oppression, and even their enslavement of them, by insisting that the victims were so low on the evolutionary ladder as to be in need of basic human development. In the extreme case, which was by no means an unusual part of the imperialist narrative, the tribal peoples who were thus invaded were said to be on the very lowest rungs of the ladder of social evolution. Just as an animal that can be domesticated is thereby rendered both useful and, it might be said, given a chance to achieve its best possible potential, so too were many of the ‘Indians’ of the Americas, the Aborigines of Australia, and the Bushmen of southern Africa- often seen as something less than human.

Two monks debate

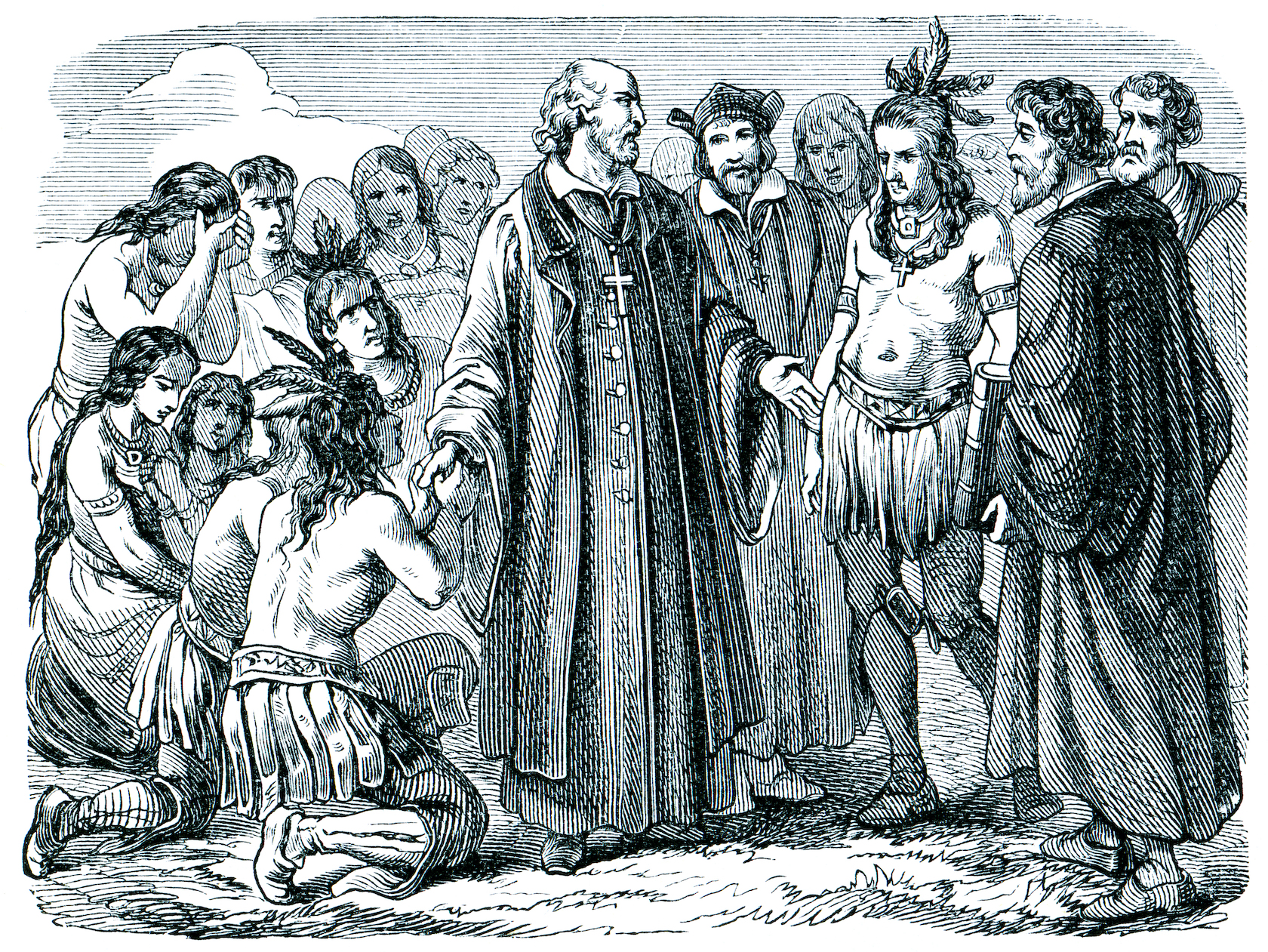

In the middle of the 16th century, the Spanish court became aware that intense criticism was being levelled against its activities in the Americas. The brutalisation, oppression, and murder of the indigenous people by the Spanish conquistadores was publicised, debated, and critiqued. So intense was this critique that, in 1550, the king of Spain decided there should be an official inquiry, a public investigation, to determine what the rights of the indigenous peoples might be.

In order to have this investigation, a debate was set up between two men of the church, two monks: Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda and Bartolomé de Las Casas. Thus, in 1550, Sepúlveda and Las Casas debated the nature of the indigenous peoples of the Americas – the first public inquiry into this crucial question.

Sepúlveda argued that, on the basis of Aristotelian philosophy- which, in his view, was beyond dispute- the indigenous peoples of the Americas were natural slaves. Aristotle had argued that humanity divided into those who were and those who were sophisticated enough to be owners and rulers, and those who, being without any such sophistication, could only develop by virtue of complete subordination. On this argument, following the Aristotelian model, the natural slaves, the inferior peoples of the world, do not have any rights to freedom of movement or occupation.

Sepúlveda used this model to make the argument that the oppression being perpetrated by the Spanish conquistadors and colonists – even the killing and torturing of indigenous peoples in the Americas – was justified. The only hope for the victims of the Spanish conquest was that they should be civilised; and, on this analysis, the only way of being civilised is being taken hold of by Europeans and turned into something else, something more fully human.

On the other side of the argument, Las Casas put forward what seems like a very modern view. He said that the indigenous peoples of the Americas, the people the Spanish had conquered, were fully human; that they had sophisticated languages, forms of government, religions and ways of managing their economies and societies that meant they were no less a version of humanity than Europeans. Therefore, to enslave, oppress and murder them at the will and whim of the conquerors was to commit crimes against them as individuals and societies, and to violate the dictates of justice and reason.

It is striking that Sepúlveda, arguing that the Indians of the Americas were natural slaves, had never set foot in South America; whereas Las Casas had spent some 40 years living with the indigenous people of the Americas – during which time, on the basis of his own experience and examination of his conscience, had gone from accepting to rejecting the Spanish colonial project.

The Las Casas-Sepúlveda debate was public and official. A panel of judges had to decide which line of reasoning was right. As the debate began, the king of Spain ruled that no further conquests should take place in the Americas, since the legality of such a process was in doubt. However, the Spanish invasions and violence against indigenous peoples did not pause. Even though supporters of Las Casas were sure that his view had prevailed, even after some 15 years of consideration, it was not clear which view had in fact prevailed, as they hadn’t been able to reach a decision. Meanwhile, the oppression and dispossession continued.

The argument that Sepúlveda was making, which runs through the history of European thought, is deeply disturbing. It persisted in different forms, often in the guise of notions of social evolution, and is evoked by the way the discipline continued to use the words ‘primitive’ and ‘savage’ to describe those whom it studied. At times, some who were said to be anthropologists provided the intellectual accreditation of the attitudes and ideas that entitled European powers to dispossess and disown and disinherit those who they thought stood in their way.

But the critique of the Sepúlveda forms of argument, and a growing challenges to the intellectual, moral and legal assumptions embedded with imperialism, became more and more a central feature of anthropological work. The voice and attitudes of Las Casas has also resonated through intellectual history.

Hierarchies taught in school

The evolutionist view of humanity – with us at the top, the others somewhere lower down, and indigenous or tribal people somewhere on the lowest level of human society – prevailed in the Enlightenment, despite the parallel and opposing notion of the “noble savage”, through the 19th century and deep into the 20th century. And there underlies a great deal of racism that we encounter now. All along the way it was opposed, but it prevailed, and can be seen at work in the educational system of the schools of Europe, North America, and many other parts of the world.

It’s considered a recurrent feature of the curriculum. The youngest children are taught about people who live as hunters – the Inuit are probably the most familiar example. Older children are taught about farmers and herders. The oldest children, the top grades, learn about industrial society and people like us. As if to say that there are some people who are simple, easy to understand, some who are a bit more complicated, and some – that is, us- who are the most complicated of all. This notion, this hierarchy of humanity, is embedded in our consciousness and is revealed and reinforced in the schools. Notions of development repeatedly echo this notion, urging that the “simple” peoples be pressed into changing in directions that are “civilized” – and, incidentally, of value to us, the ‘developers’.

I began my anthropology in North America by going to the people who were supposed to be at the bottom of the evolutionary ladder: the hunter gatherers. I want to situate the problematic of being an anthropologist in the hunter gatherer world of the high Arctic with a brief account of the first time I was taken out onto their land by Inuit hunters.

I was living in the settlement of Pond Inlet, at the north tip of Baffin Island, far above the Arctic Circle. I had been there only a week when I was taken by an Inuit elder called Enugu and his son, Willy, and a team of 12 dogs, on a fishing trip. We were to go to the mouth of a river which would take two days to reach. This was my first chance to see how a hunting system functioned, and an opportunity to travel by dog team.

At the first place we stopped to sleep, after some eight hours of moving across the sea ice, we set up camp at the bottom of a steep ravine. I decided to walk up to the top of the ridge above the ravine. After clambering my way over rocks and up to the peak, I found myself looking out over the north end of Baffin Island, far across the high Arctic. It was one of the most stunning spectacles you can imagine: stretching far away in front of me was a vast landscape of frozen fjords and range after range of snow-capped mountains. I could see across hundreds, if not thousands, of square miles. But there was not another person, no sign of any community. Just Enugu, his son, and the 12 dogs, at a tent beside the ravine, down by the edge of the ice.

I thought to myself, ‘This is an experience I must never forget. The emptiness, the wildness, that wilderness’. I often think back to what went on in my head at the top of that escarpment. Emptiness, wildness, wilderness: these are all terms that came from my imperial heritage. But for Enugu, there was nothing empty about this landscape. It was not wild. It was not wilderness. For him, this was the center – not an edge – of the world.

Enugu lived in an extremely sophisticated, civilised domain. Every part of that land had its place in his mind: structures of knowledge, skills, ways of behaving - this world of his that was the north shores and lands of Baffin Island. And my job, I realised, was to shed completely my assumptions, my ideas about the landscape, and immerse myself in his ideas, his intellectual systems, his way of life. It was my job, as it is the job of every anthropologist, to spend my time and energy listening to what they could teach me. I could do my job by learning from them.