Of all the elements of the First World War partition diplomacy, perhaps the most decisive and fateful was the Balfour Declaration, in which the British government in November 1917 pledged its support for the creation of a Jewish national home in Palestine. The terms of the Balfour Declaration promised that this Jewish national home would not come at the expense of the civil or religious rights of the non-Jewish population of Palestine.

It was the beginning of a fateful alliance between the British authorities and the Zionist movement that was a way to legitimate Britain’s attempt to revise the terms of its wartime negotiations with Russia and France, particularly in the Sykes–Picot Agreement. Before the Agreement, Britain, France and Russia couldn’t agree who should get to claim Palestine to their Empire. After all, each of the three States had a spiritual interest in the Holy Land.

The wartime experience, particularly the strategic challenge posed in the Sinai war and the Palestine conflict, had given the British a clear strategic concern. They determined that if they didn’t control the southern frontiers of Palestine, an opposing party based in the country could threaten shipping in the Suez Canal. Such a party simply needed to move artillery into the waterless wastes of the Sinai. Then, from 10 or 15 miles away, they could fire artillery to close the shipping lanes.

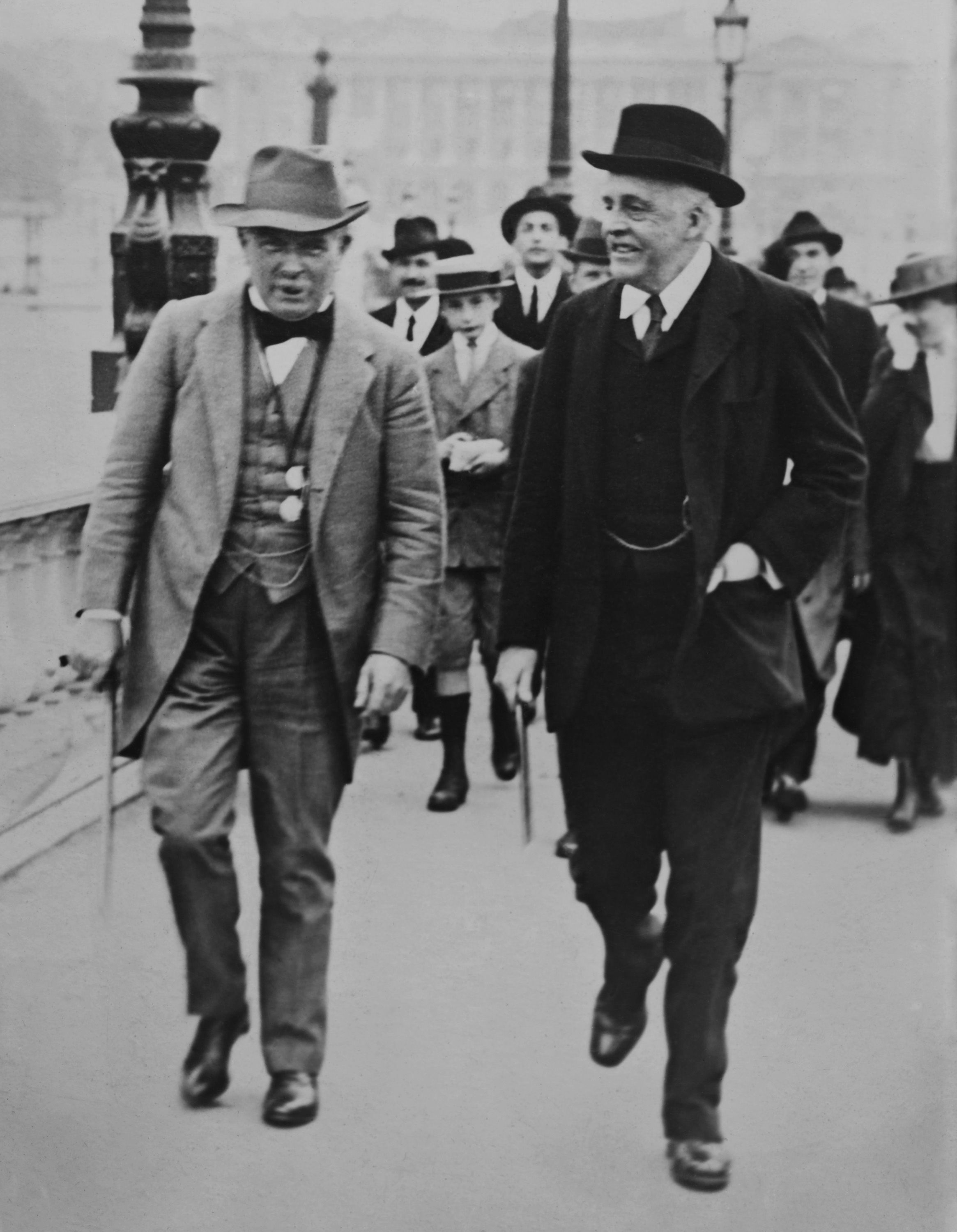

Partnering with the Zionist movement

As such, Britain engages in a partnership with the Zionist movement as a way of justifying a claim to Palestine, which they previously had felt uncomfortable trying to make. After all, there were Russian and French claims to the holy places of Palestine as well.

Regardless, in the Arab world, there’s always been the perception that British support for Zionism was intended to divide the Arab world between its African and its Asian provinces. It would achieve this by putting a partner community in this juncture between Asia and Africa, a kind of buffer State.

For the British, the Zionist movement was precisely the kind of compact religious community whose interests would be advanced by the British mandate. This would also make the Zionist organisation in Palestine willing collaborators.

The decisive conflict played out in two phases between a United Nations General Assembly resolution in November 1947. This resolution recommended the partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab States as a patchwork of territories. These territories lacked any congruity that might make them look like viable countries. This action begins a civil war between the Jewish and Arab populations within the Palestine mandate before the British have even withdrawn.

After 15th May 1948, the territory of Palestine is invaded, in the immediate aftermath of Britain’s withdrawal, by the neighbouring Arab States. In so doing, the Arab States hope to suppress the newly declared State of Israel and to support the liberation of Palestinian territories from Zionism.

Israel’s victory

This invasion leads to the first Arab–Israeli conflict and the total victory of Israel over its adversaries. It also results in the consolidation of 78% of the landmass of the Palestine mandate under the control of the new State of Israel. This is in accord with armistice lines concluded between Israel and its Arab neighbours in January and February of 1949.

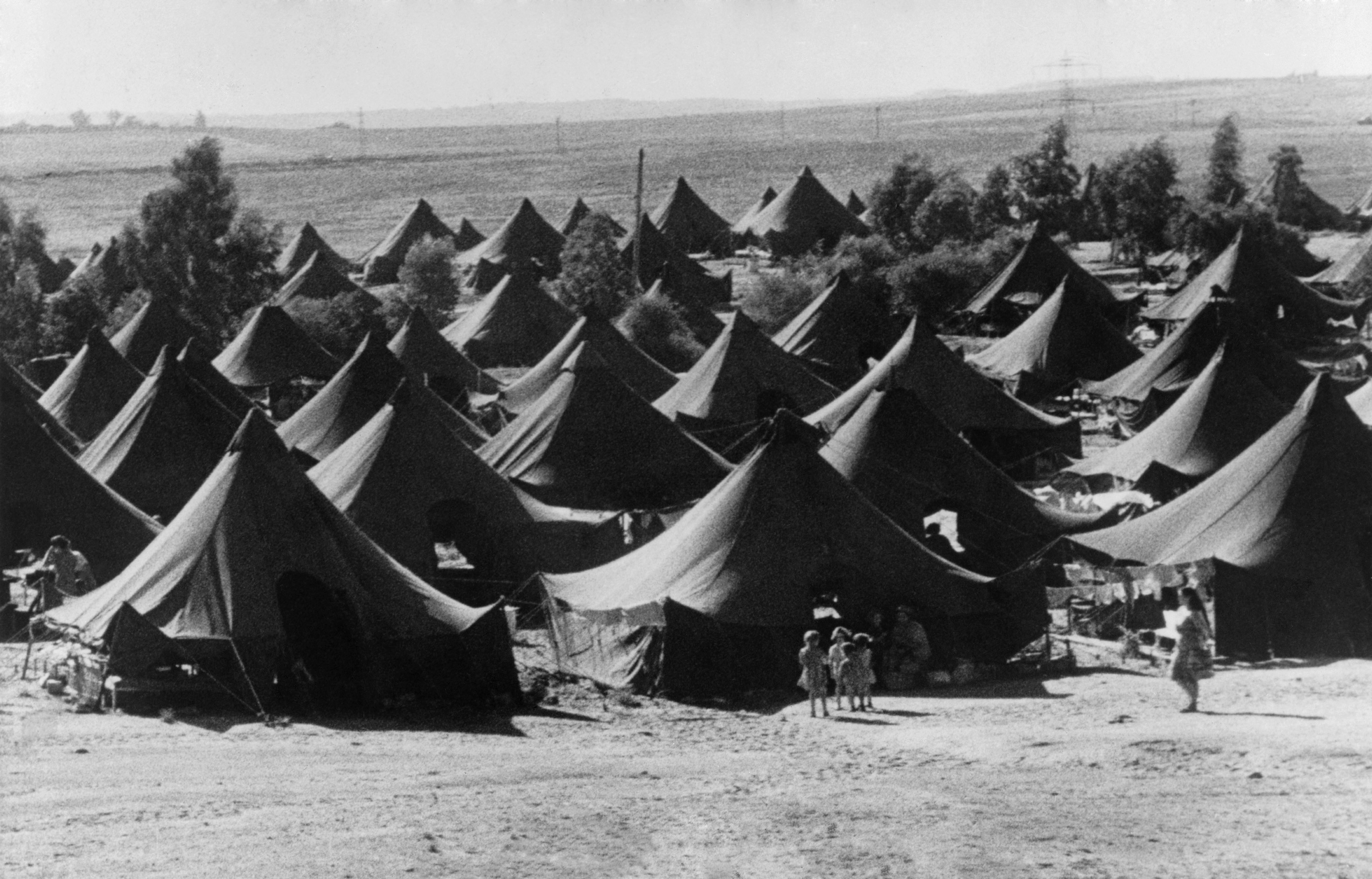

The establishment of the State of Israel results in the dispersal of 800,000 Palestinians as refugees to surrounding countries such as Lebanon, Syria and Jordan. It also leads to the creation of a hostile war footing between the new Jewish State and the surrounding Arab States. This tension was to enhance the fragmentation of the Middle East and define it as a zone of conflict for the entire second half of the 20th century.

Coming out of the war

The 1948 war is one of the most heatedly debated features of modern Middle Eastern history. There is an Israeli narrative of the miraculous triumph of Jewish forces over so many adversaries. Throughout these conflicts, the Israelis were sorely outnumbered demographically by their opponents and yet managed to triumph over them.

There is the narrative of the Nakba and the dispossession of the Palestinian people. Indeed, the Palestinians were driven from their ancestral homeland. The violence of this conflict forces civilians to seek refuge in the safety of neighbouring States in the hope that they are allowed to return to their homes when peace is restored.

In subsequent years, historians have benefited from the opening of archives. They have been able to break down the myths of this bifurcation of the miracle of the creation of Israel, the tragedy of Palestine and the betrayal of Arab forces. They have determined a history which, in effect, can explain the outcome of the 1948 war very much in terms of Israeli unity of purpose and Arab fragmentation.

Israeli unity and Arab fragmentation

The Israeli unity of purpose is relatively easy to explain. The horrors of the Second World War are fresh in the minds of the Jewish people. Their immense suffering begets a determined desperation driving the forces of the Zionist movement and the Jewish population into Palestine. There, they aim to establish a haven for the surviving Jews of the world and create a country removed from the threats of anti-Semitism, mass murder, extermination or genocide again.

On the other hand, the Arab States involved in the 1948 war faced their first challenge when they confronted the newly declared Jewish State. Most of them had only just secured independence a year or two before the 1948 war. A handful were signatories of the UN Charter in San Francisco in 1945, where they gained recognition as independent of Britain and France. In Syria and Lebanon, the final French withdrawal only came in 1946.

In other words, the Arab States were not well prepared to address the challenges that an inter-Arab alliance against the Jewish State would impose. Moreover, these States were weak in their frontiers. Governments felt insecure that they had the full loyalty and support of all of their populations. They were also wary of their neighbours who might attempt to expand their national frontiers at the expense of others.

Rumours surrounding Transjordan

At this point, the new State of Transjordan was under a lot of suspicion. This is due to rumours subsequently substantiated that the Hashemite monarch of Transjordan, King Abdullah, had been in negotiations with the Zionist movements. These discussions took place before, during and after the 1948 war, resulting in an agreement, or modus vivendi, that Jordanian troops would move in and occupy those territories allocated by the UN partition plan to a Palestinian Arab State. This is something that the neighbours of Transjordan, particularly Egypt and Saudi Arabia, found very concerning. These countries were distrustful of the Hashemites in Transjordan, and were committed to denying them their plan.

As a result, we see the Arab States enter the war against Israel, not as a unified bloc with a common purpose, but rather as a series of weak, newly independent States. They are vulnerable because colonial powers had worked to ensure that there wasn’t a strong executive in any one of their countries. This is something the British and French were very effective at. They undermined the nationalists in the region who attempted to weaken the imperial position. Sure enough, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, Palestine and Egypt remain fragmented among themselves.

For the Palestinians, 1948 is the year of the Nakba. The word in Arabic means catastrophe, and it was a total catastrophe for the Palestinians. Not only were they denied the national aspirations of creating a government, but they were driven from their homes by the hundreds of thousands. They tried to find sanctuary in neighbouring countries whose hospitality varied according to the terms under which the Palestinians entered their country.

For Lebanon, the influx of Palestinians put a real strain on their system of government. Their division of political office was made following the demographic weight of different religious communities. Lebanon has a confessional political system in which the president was and still is a Maronite Christian. The prime minister is a Sunni Muslim, and the speaker of parliament is a Shiite Muslim.

Furthermore, in Lebanon, the division of parliamentary seats is apportioned in a six to five ratio in which Christians and Jews would get six seats for every five that went to Sunni, Shiite or Druze, or Muslim members of the body politic.

The sudden influx of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees, who were mostly Sunni Muslims, was a real threat to the balance of political power in Lebanon. So, the Lebanese, while giving them sanctuary, confined the refugees, ensuring that they never achieved integration or assimilation within Lebanon. Allowing them to do so would have given the Sunni population of Lebanon a massive boost that would have destabilised its politics. Lebanon always defended the rights of Palestinian return because they never wanted to allow the Palestinians to remain.

The Palestinian political movement

In the Six-Day War of June 1967, Israel defeats the military of Syria, Jordan and Egypt. It also extends its territory to the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights and all of the Sinai Peninsula. This represents a massive territorial loss for the Arab world and the bankruptcy of the Arab National Political Project.

At this moment, Palestinian militias begin to gain a margin of freedom from Abdel Nasser’s control to pursue their own measures for the liberation of Palestine. This armed struggle for the independence of Palestine was going to shape the 1970s. The political life of refugee camps in Lebanon also shifts to allow Fedayeen mobilisation and commando mobilisation to prosecute a war on the actual territory of Israel and Palestine.

The effort also seeks to try and revive the debate about Palestine in the international context through hijackings and other terror tactics. As such, it hopes to restore Palestine to the headlines, even as negative news, so that people would remember that the Palestinian people remained an unsolved problem. In that sense, through armed struggle, the Palestinians find a way of imposing their political aims in the hope that they might then have a strong enough position to come to the diplomatic table. There, they hope to negotiate for a resolution of their legitimate national aspirations against the Israeli occupation.