Arendt’s potent use of irony

There’s this extraordinary moment in an interview that Hannah Arendt gave in 1964 on German television with Günter Gaus. She says that when she read the transcripts of Eichmann’s interviews with the Israeli secret services, she just laughed out loud. ‘I laughed and laughed and laughed,’ she said.

It’s hard to think of a more singularly inappropriate way to respond to the memories of a mass killer, and to some extent, that was what got her into trouble with her reports on Eichmann in Jerusalem. She wrote in this kind of brutally ironic way, as if she didn’t care.

Irony, of course, can be defensive. People have said that Arendt just couldn’t come to terms with the horror of the Holocaust, so she used irony as a form of defence and a way of distancing herself from it. She’d lost so many friends and family, and her life had been devastated. Maybe there’s something in that, but I think that she used irony very seriously. She laughed seriously.

This goes back to why thinking and perplexity are so important to Arendt. When she used irony, what she did was to critically foreground and “defrost” the banality of evil and, particularly, the banality of those statements.

To give an example, her good friend – about to be her ex good friend – Gershom Scholem, who was a great scholar of Jewish mysticism and Jewish theology, was furious with Eichmann in Jerusalem. He said to Arendt, ‘At one point you call him a Zionist! What are you talking about?’ Her answer was that she was talking ironically. She was referring to that moment where Eichmann turns around in Jerusalem and says to the court, ‘Well, I’m a Zionist; I’ve read Theodor Herzl; I’m a committed Zionist’ – without realising the contextual, situational and morally obscene irony of saying that when you are on trial for the murder of 6 million Jews.

The limits of the sayable

Irony produces a dissonance in Arendt’s thinking. She loved it as a tool and she used it as a form of judgement. I often go back to a point that the great W. G. Sebald once made. He was talking about Jean Améry, a Holocaust survivor, who also uses irony a lot. Sebald said that irony takes us to the limits of the sayable. It’s that point where you can only repeat the obscenity; and in that repetition, you are revealing the horror and the meaninglessness of those statements.

For Arendt, the ironic voice was terribly important as a way of countering the banality of evil. The laugh wasn’t ‘Ha ha ha. He’s insignificant’; the laugh was to say that there’s this moral gap that’s opened up, where only irony can be located.

Why we need storytellers

There’s a famous essay that Arendt wrote called “Lying in Politics”, which is now very popular for, perhaps, obvious reasons: people want to understand what it means to have a culture where we have habitual lying and nobody seems to care. What’s often missed about that essay is the section where Arendt talks about the figure of the storyteller. She’s drawing from her old friend, Walter Benjamin, who committed suicide as he was trying to escape Nazi-occupied Europe. In his essay “The Storyteller”, Benjamin says that the storyteller, as a person bringing judgement and making sense of the world, is a disappearing figure. Technology has taken over. There’s too much communication, too much repetition. We’re losing wisdom.

In “Lying in Politics”, Arendt says that the storyteller has a political function. Whether they’re a historian or a novelist, the storyteller’s job is to make us accept reality for what it is. This sounds counterintuitive: storytellers are well known for making things up. But what she’s saying is that storytellers – the best historians, the best novelists, etc. – reveal something that’s difficult for us to comprehend or face up to. That then allows judgement. We’re not going to be able to judge if we’re simply looking at competing fictions of the world.

We can see this in the culture wars. What we need to do prior to that is to have the storytellers and the historians who can give us the forms of understanding through which we can comprehend an appalling reality.

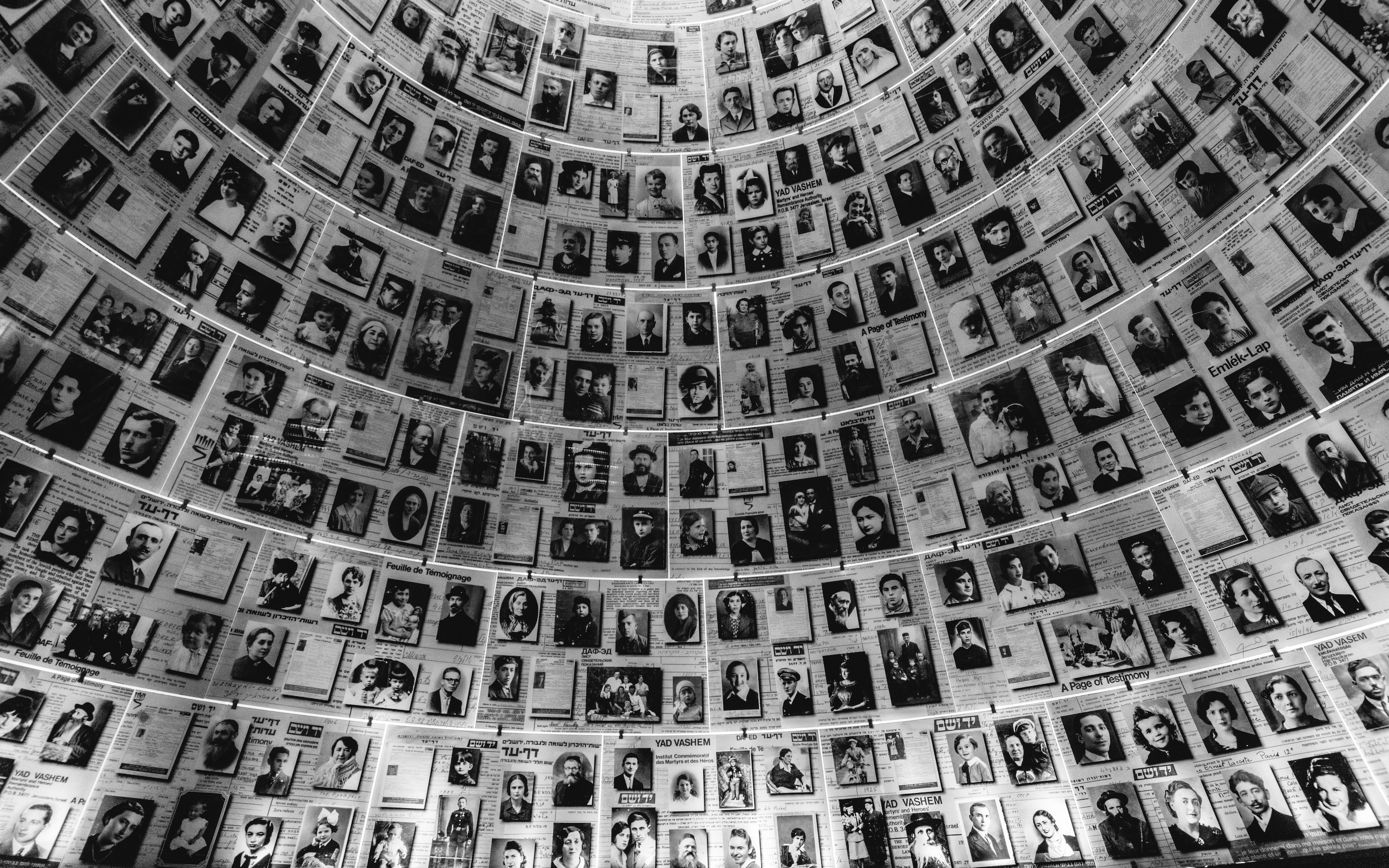

What Arendt wanted people to do is never believe that the impossible can’t be possible. This is why The Origins of Totalitarianism is such an important text in the historiography not only of the Holocaust but also of 20th century politics. The Holocaust seems incredible – but the turning of human bodies into corpses on a systematic, industrial scale happened. This, she said, is what we have to look at. We have to look at what things are happening.

That leads us back to that attention to language. How can you have a forceful, intelligent, thoughtful critique of these things that are seemingly being done for other reasons? Be very attentive to those moments in which language lives free of context, because something at that moment has slipped into the culture.

With Eichmann, by calling the system that produced the murder of Europe’s Jews banal, was Arendt saying that she thought the crime was banal? No. She thought the opposite. The crime is one of the worst things that’s ever happened in the history of Europe, but the means by which the crime was committed were banal. That’s hard to think about, but that’s also our reality.

Totalitarian States will fail, she said, towards the end of The Origins of Totalitarianism, and, of course, they did. However, she also said that totalitarian elements will remain in culture, enabled by thoughtlessness in institutions, capitalism and politics.

The loneliness of the conspiracy theorist

Loneliness is key to Arendt’s understanding of what allows totalitarian or fascist systems to come into play. She talks about several types of loneliness. There’s the loneliness that goes with modern culture and makes people very susceptible to conspiracy theories – fictional versions of the world in which there are villains and everyone’s out to get you, rather than the version of the world that says you’re totally insignificant.

You can see that in conspiracy theories today around COVID-19. Rather than thinking this is an awful disease that may or may not kill me, conspiracy theory feeds into the idea that, no, people are out to get you because you’re really important.

Another kind of loneliness arises when the world no longer makes common sense. Kant was a great believer in the idea that we had to share a sense of what the world was grounded in. Once that goes and you just have competing opinions, loneliness sets in. You simply don’t know what is true anymore. That’s an epistemological crisis, but it’s also, as Arendt would say, a moral and political crisis.

Towards the end of her life, Arendt wrote on the crisis in the American Republic and, particularly, on civil disobedience. This was in the context of 1968 and onwards: student protests, the Vietnam War and the movements against Nixon.

Civil disobedience was important to Arendt because, for her, to dissent from the way you’re being governed was part of the contract that also allowed assent. They are two sides of the same coin. Civil disobedience was key to that idea of what it meant to be an active citizen, but not just because of your individual consciousness. This goes back to what we’ve been saying about thinking. Thinking might be something you do by yourself. Thinking might be where you disappear from the world. But judging can only be done within a political community, and civil disobedience en masse is, as it were, the collective judgement of people on the way they’re being governed.

If Arendt were alive today, I think she would have thoroughly approved of Black Lives Matter, while probably being a bit squeamish and embarrassing about it as well. She would probably put limits on it, though she would certainly approve of what’s happening in Belarus, Poland and elsewhere where people are actually creating their own truth on the ground, sticking up for that version of reality by collective action and civil disobedience.