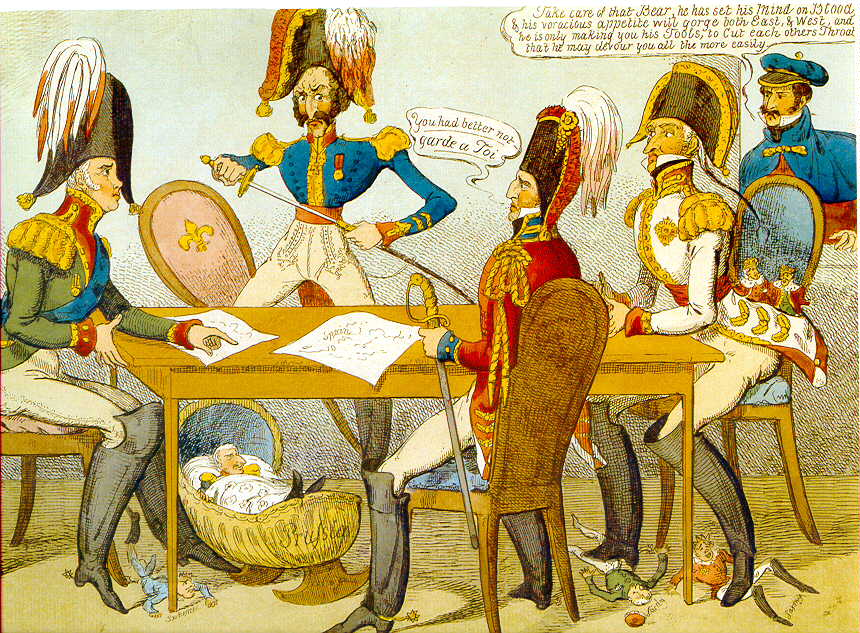

In 1815, the future of Europe is settled at the Congress of Vienna. It’s interrupted by Napoleon’s reappearance, but after Napoleon’s final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in the early summer of 1815, the new settlement is imposed on Europe by the main powers. The monarchy is restored in France; Britain and Russia are the two dominant powers, but they work with Prussia, Austria and France in a kind of European union.

Some people think that the peace settlement of 1815 is a restoration of the old balance of power, and others think that it’s the fig leaf for an Anglo-Russian hegemony. Another way of looking at it is that it is a system of institutionalised European cooperation. Ideologically, the powers of Europe are all on the same page. The French radical revolutionaries have been defeated. Republicanism has been defeated. The monarchies have been restored.

Holy Alliance

Yet there are religious differences: Britain and Prussia are Protestant, France and Austria are Catholic, and Russia is Orthodox. The Christian powers of Europe don’t belong to the same church, but 1815 is also the year of the Holy Alliance: a coalition between Prussia, Austria and Russia that aims to move beyond that religious disagreement.

We see in the politics of 1815 something that we’ve become used to in recent years: frequent summits. The European powers are in constant communication with one another. Every year there’s some international meeting of rulers, senior ministers or senior diplomats.

The powers of Europe present a united front against the forces that they think might challenge them: liberalism, nationalism and socialism. Ultimately, these are forces that have a life beyond the narrow horizons of the great powers of 1815 – but the politics of 1815 is very much about keeping them in their box to avoid the repeat of something like the French Revolution.

Visions of European cooperation

There’s a great deal of European cooperation in 1815. Konrad von Schmidt-Phiseldeck, a German who runs the National Bank in Copenhagen, is interested in what he calls a europäische Bund – a European union that will emerge as a response to commercial competition from Russia on the one hand and America on the other.

Alexander Hill Everett, an American observer, thinks that out of this ceaseless practice of summiteering and increasing coordination between different European governments, something like the American system will emerge in Europe. He doesn’t call it a United States of Europe, but that language becomes increasingly common over the course of the 19th century. Everett’s idea is that this institutionalised cooperation in Europe will give rise to something similar to the political system of the United States, except there won’t be a revolution or a dramatic founding moment. It’s a system that will emerge over time.

That is the conservative vision of European cooperation; it’s built on the settlement of the Congress of Vienna and the institutionalised cooperation to which that gives rise. This order has figures like Metternich, the Austrian foreign minister, and his secretary, Friedrich Gentz, at the heart of the system, managing European international affairs in a more or less coordinated way.

It’s against that vision of a harmonised Europe that a left-wing vision of a unified Europe as an alternative emerges. A key figure in the first half of the 19th century is the Italian nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini. Part of the 1815 settlement is the Holy Alliance between Prussia, Austria and Russia, and Mazzini says, we need a holy alliance – but a holy alliance of the peoples.

A lot of the rhetoric of European unification that comes from republicans, figures on the left and revolutionaries in the first half of the 19th century targets the Vienna settlement. There are different views about the French Revolution and why it went wrong, but these people often imagine that the immediate political problems are the monarchic, religious, authoritarian, illiberal, undemocratic governments in Europe.

Just as these governments have formed an international league with one another, the opposition movement will also be transnational. There will be activists in France, in Germany, in Italy and elsewhere. Their vision for Europe is of a holy alliance of the peoples and the emergence of national sister republics living side by side, with relations not of competition and enmity but of fraternal cooperation. That word fraternité, one of the ideals of the French Revolution, remains important in the 19th century.

A free Poland

One of the political issues that appears repeatedly in this literature concerns Poland. The Ancien Régime powers in Russia, Austria and Prussia destroyed Poland in the late 18th century through three partitions, which ultimately meant that Poland was wiped from the map of Europe. Through the 19th century, one of the common causes of the left concerns the liberation of Poland – what it would take for Poland to be free.

There is an uprising in Poland around 1830, and many of the Polish exiles end up in Paris. One of the revolutionary students in Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables is Feuilly, the fan-maker, who thinks that everything in the end turns out to be about Poland. An analogy can be made with the way that Palestine figures in the discourse of parts of the left today; there are people who, whatever the question is, can bring things back to the importance of ending the Israeli occupation of Palestine. The question of Poland had a similarly talismanic property in the middle of the 19th century. There were visions of a world of fraternal republicans bound together in a European confederation, but a key element was a free Poland – Poland restored to the map of Europe.

The question of borders

It’s significant that when people are talking in this vein, one of the disagreements that they continue to have is over exactly where the frontier between France and a German confederation should be. There are French writers like Victor Hugo, an important advocate of what becomes called the United States of Europe, who wants France to have her natural frontiers restored. That means French territory should extend to the banks of the Rhine. Plenty of Germans who are taking part in this discourse of European cooperation absolutely don’t want that; they don’t want French power extending right up to the Rhine and therefore able to be projected over the western part of Germany.

Even when people are talking about fraternal international cooperation, as they are at the Hambach Festival in Germany in 1832, this question of where the border between France and the German lands will fall is one that they continue to disagree on. It becomes an incredibly important issue over the next hundred years. Once the Prussians take Alsace-Lorraine after the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, the French are continually imagining a future war, a war of revanche, to take back Alsace-Lorraine and make it part of France.

We only get the emergence of a stable European confederation in the post-war period when the Franco-German border is no longer an issue, when German expansionism has finally been defeated and the French are content with the frontiers of the country – with Alsace-Lorraine being part of France, Luxembourg being independent, Belgium not being part of France and so on. These questions about the borders become critically important. Interestingly, disagreements about the borders emerge in the discourse of those figures on the left who are most enthusiastic about the prospect of a European confederation of sister republics in the early part of the 19th century.