And at the moment, there certainly aren't many women in the upper levels of science, even though we have equal gender legislation. So, for me as a historian, I think it's crucial to explore the past and examine how those prejudices and obstacles that women faced in the past are still affecting women today. The whole point of understanding how we've reached the present is to improve the future.

Marie Curie, Rosalind Franklin and women's roles in the history of science

Emeritus Fellow of Clare College

- Until the second half of the 19th century, women were barred from universities, restricting their opportunities to practise science.

- As well as great discoveries, the history of science must take note of communication, translation and teaching, all of which involved influential women.

- By understanding the origins of prejudices against women scientists, we can increase the number of women in science and improve their position and status.

Where are the women in science?

There aren’t many women in the history of science and I think it's important to understand why. After all, the past affects the present and the present affects the future.

An illustration of a woman teaching geometry, from a medieval illuminated manuscript of Euclid's Elements (c. 1310 C.E.) © British Library Wikimedia Commons

Redefining the history of science

The most obvious reason why there are so few women in the history of science is that until the second half of the 19th century, they weren't allowed to go to university. Unless they were extremely wealthy and could afford to employ private tutors, there was no opportunity for women to carry out the same experiments as men. There was also a general cultural belief (held by women as well as by men) that women were fundamentally unsuited to carry out that sort of intellectual work.

There were, however, quite a few women engaged in scientific pursuits, and if we think more carefully about what it is we mean by the history of science, they become more visible.

It's very tempting to focus on a few individuals like Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein and imagine a sequence of great geniuses, inevitably male, lurching from one discovery to the next. But of course, that's not how science really develops. There's a lot of collaboration. There's a lot of people behind the scenes who are actually carrying out the experiments. It’s crucial for the results to be communicated widely, so that people can develop them and build on them. Isaac Newton, for example, said that he deliberately made his mathematics very difficult because he didn't want to be pestered by what he called “little smatterers” in mathematics. It's fine for him to sit under the apple tree and have an inspiration, but if he doesn't tell anybody else about his ideas, science isn't going to advance. And that's one of the ways in which women come in.

The forgotten communicators

There's still only one translation of Isaac Newton's work on gravity into French. And that's by a woman, Émilie du Châtelet. Not only did she translate it, but she added lots of notes and a long commentary. Later in France, another scientist developed the version of Newtonianism that we accept today. And for it to be understood in England, it had to be translated back into English with an explanation of the mathematics. That was done by another woman, Mary Somerville.

Those are just two examples of how women played a very important role in translating from one language to another, and from one country to another. During the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, a lot of scientific research was happening inside people's private homes, not in public laboratories. That meant there were large numbers of women who were actually there helping their husbands or their brothers or their fathers, but they're left out of the records.

Inspiring Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday never went to university: he was self-taught. His first introduction to chemistry was through a small book written for children by a Swiss woman called Jane Marcet. Faraday paid tribute to her right to the end of his life.

She’s just one example of how important women can be in teaching science. If we get away from a history of science that is just a succession of great geniuses and great discoveries, and set up a more realistic model of how science progresses, involving illustration, translation, communication, editing, making apparatus, then women start to play a more crucial role. But it is also the case that even after women could go to university, they were very much discriminated against. One problem is that we tend to make heroines of the few women who have reached the top in science, and by doing so, we’re replicating the same “great discoverer” story we applied to men.

Marie Curie: a poor role model?

Photo by Morphat Creation

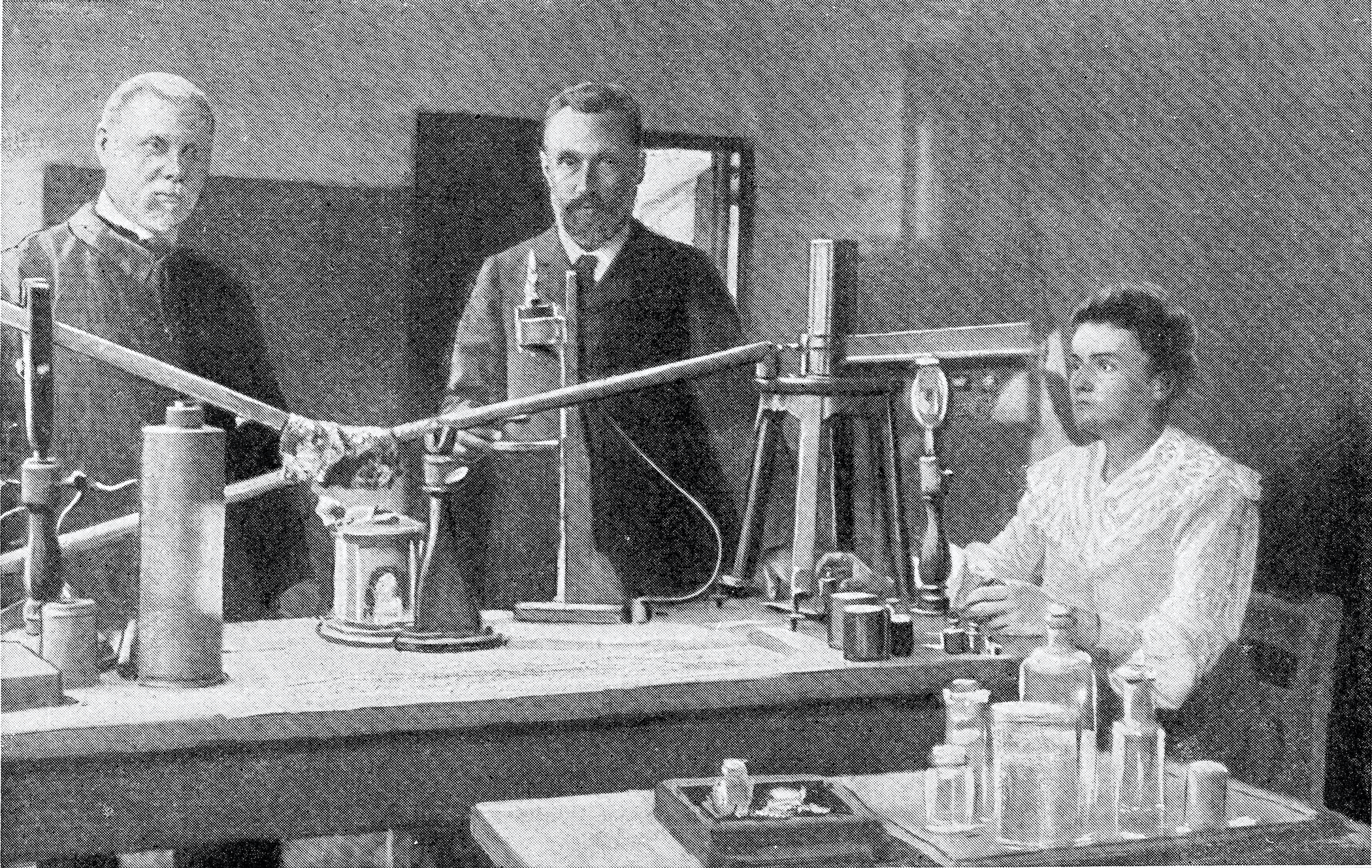

Undoubtedly the most famous woman in the history of science is Marie Skłodowska Curie, the woman who travelled from Poland (where she couldn't get a university education) to Paris, where she got her degree and Ph.D. and married her one-time supervisor, Pierre Curie.

She's extremely famous for her research into radioactivity. She was the first person, not just the first woman, to be awarded two Nobel Prizes. So, naturally, she has become a great heroine of science.

I think it's very easy and tempting to fictionalise her story and translate her into a martyr to science. We hear a lot of stories about how she sacrificed her normal life. She was a wife and mother with two little girls, but she spent weeks and months in a very dirty, ill lit, tiny shed, sieving tons and tons of pitchblende. She often went for days without food. She wasn't interested in her clothes. She just dedicated herself to a life of pure scientific research. That's an idealised, mythologised version of what her life was really like. And I think by concentrating on those aspects, we actually have converted her into a rather poor role model for other women.

Rosalind Franklin: the woman and the myth

Probably the second most famous woman in the history of science, certainly in Britain, if not abroad, is Rosalind Franklin. She is most famous for working on the double helix structure of DNA, for being deprived of a Nobel Prize and for being bad-mouthed and criticised by James Watson.

There are several things about this story that I don't like. Most importantly, her story is being subjugated to the story of a man. The story of Rosalind Franklin isn't being told to celebrate her achievements. It's being told to show how unfairly she was treated by a man.

There’s a very different way of telling the life of Rosalind Franklin. If you look at her gravestone, which is in a Jewish cemetery in Willesden, the inscription on the gravestone is very simple. It just says: “Scientist: her work on viruses was of lasting benefit to mankind"

.

A virus pioneer

Since the spring of 2020, virology has become a preoccupation. We all would like to celebrate the people who helped to discover viruses, and that's where we can tell a far more interesting and worthwhile story about Rosalind Franklin.

As soon as she managed to escape from King's College, she went to work for J.D. Bernal at his lab at Birkbeck College. She started working on something called the tobacco mosaic virus, which might not sound very exciting. It makes tobacco leaves mottled green and yellow. It was the first virus to be isolated and crystallised. Its structure is much more complicated than the structure of DNA, but she managed to work out what it was and then she went to work on other vegetable viruses.

Later, she started work on the virus that causes polio. This was in the early 1950s when a polio epidemic was devastating thousands and thousands of lives, especially the lives of small children. A younger scientist called Aaron Klug joined her team.

Franklin died very young from cancer. She was only in her 30s. She had published a whole raft of scientific papers and was incredibly well recognised as an expert on viruses. Aaron Klug went on to win the Nobel Prize for his research into the polio virus. It seems very likely that if Franklin had lived a bit longer, she would have won a Nobel Prize.

I think this positive story of Rosalind Franklin as a pioneer of virus research is much more interesting. It's much more worthwhile to tell that story to young women to encourage them to follow a scientific career.

An ongoing struggle

Photo by Louis.Roth

Although we have equal opportunity legislation, and in principle women and men are paid the same for doing the same work, it is still true that, on average, women in science earn rather less than men do. It’s also the case that there are relatively few women at the upper levels of science, such as heads of laboratories and professorships.

A lot of the prejudices that were held against women in the past are still held today. By looking at the past and by understanding the origins of those prejudices, we can start to make some headway in the very important struggle to increase the number of women in science and to improve their position and status.

Discover more about

women in science

Fara, P. (2017). Pandora’s Breeches: Women, Science & Power in the Enlightenment. Pimlico.

Fara, P. (2018). A Lab of One’s Own: Science and Suffrage in the First World War. Oxford University Press.

Fara, P. (2017). Case Study: Hertha Ayrton. In P. Wynarczyk, & M. Ranga (Eds.), Technology, Commercialization and Gender (pp. 235–244). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.