I don’t think we’ve learned everything we can from art. Art has always been about asking questions and thinking about culture, and maybe critiquing culture or questioning culture. Our culture is always changing, and the people that inhabit culture are always changing. So, I don’t think we’ll ever learn everything we can from art. It’s a continual coevolution with human culture and human experience.

One of the benefits of art is to challenge and question things in society, such as this new technological age that we’re in that’s continually growing, increasing and providing challenges to humans in terms of how we think and experience the world.

An essential part of the conversation

Art is ever more useful as a vehicle, not the only vehicle, but one possible vehicle for reflecting back to us the changes that are happening in our society. This can be through visual art. It can also be through film or literature or music, but art has an essential role to play and is an essential part of the conversation. With digital technology specifically, there are so many things that are changing about how we experience the world, from how we communicate with each other to how we learn, to how we remember. We’ve adapted so quickly to these new technologies without always thinking about the longer-term implications of that, or what it might mean for future generations, the way we’re producing and collecting data. So, art can also play a role now in helping us think about the ways in which these technologies, while very beneficial and convenient in some cases, are also potentially problematic.

The Moral Labyrinth

One of my projects that deals with questions around technology and ethics is a project called the Moral Labyrinth, and it’s inspired by a concept that’s become popularised in a time of artificial intelligence, called the value alignment problem. This essentially questions whether and how a technology will act in accordance with the values of the society that it serves. Now, this is a very difficult challenge because there are many different values. There are different cultural values in different societies, and even as individuals, we have many different values that are not always in alignment with our other values.

In the case of AI, these technologies are being programmed by very specific people in specific contexts and often are used in completely other contexts, not necessarily taking into account the values of the individual people in that community. Even when it’s not something that’s made in Silicon Valley and shipped across the world, it’s still a problem because of our own competing and conflicting values and the values that get embedded into that particular technology. So, what the Moral Labyrinth does is create as a starting point a place for people to question their own sets of values and where those values come from.

My background is in philosophy, and I’ve always been interested in ethics, especially applied ethics. It’s really important to be continually questioning ourselves and where our beliefs and judgements come from. In the case of the Moral Labyrinth, it’s basically a walking labyrinth that almost looks like a meditation labyrinth. There’s one path that goes to the centre and then back out. The labyrinth has been shown in different places at different sizes and scales, and made out of different materials. Rather than just being traditional lines of the labyrinth, the lines are made of questions, and some of the questions are kind of whimsical and playful; some of them seem a little bit more serious or direct. There’s a range of questions, but each of those questions relates to our kind of ethical framework that has some correlation in technology.

Some of the more playful questions would be things like: is a dog moral; is a tree moral? Some of the more serious or philosophical questions are things like: what makes “wrong” wrong? Is justice a property of the world? Would you trust a robot that was trained on your behaviours?

The challenge of value alignment

You are meant to think about them and reflect on them as you walk to the centre of the labyrinth and then back out. In a traditional labyrinth, you travel a path and come out where you began, but you have undergone some kind of journey and experience. The goal of this is really to encourage people to start reflecting more critically on their own value systems, because what most people realise in walking the labyrinth is that their answers to certain questions conflict with their answers to some other questions, even when they’re just having this internal dialogue. That’s really important to realise, because it encourages a certain kind of humility that often we don’t have when it comes to our belief systems and a certain compassion and maybe more understanding for other people’s belief systems. It also elucidates the challenge of value alignment. If any set of values are meant to be embedded in a system, clearly it’s going to be challenging if, even as individuals, we don’t have a coherent sense of values.

Art asks good questions

So much of the work that we’re doing as scholars and thinkers in modern and post-modern society is around answers: conclusions, studies, something that’s linear, fixed and conclusive. Art is kind of the opposite: art opens up possibilities; art, successful art, in my opinion, asks a good question and doesn’t provide an answer. What that does is enable viewers to interact with the art and think critically about what their answer might be or how they might interpret it. That’s space for interpretation, which is, and has always been, essential to what art is, and something that’s not really encouraged in other domains. I don’t think art unilaterally is a solution to the world’s problems, but I do believe that it’s really important to have an avenue to open up these questions that don’t have answers. Some of the most important questions we ought to be asking right now don’t have answers. One other thing I’ll add is that the incentive structure in our society, in most societies, is set up for answers and not for questions that don’t have answers. Those kinds of questions make people uncomfortable, understandably. Sometimes we’re spending our energies on the wrong things, so making sure that we create and hold space for these hard questions that may not have an answer for 50, 100 or 1,000 years – there’s a really important space that that opens up.

Good intentions are not sufficient

There are a number of things about human morality and humans more generally that I have learned through the process of creating the Moral Labyrinth. One is that good intentions are not sufficient for good systems or good outcomes. It’s a common fallacy that if you mean well, then you’re not doing any harm, and that is not the case at all. One example that’s actually from the labyrinth is a question that says: is it wrong to kill ants? It sounds like that’s really just about killing ants, but one of the examples I use is: if there’s a little kid on the sidewalk stomping on ants trying to kill them versus a mother and her child walking down another sidewalk, enjoying the sunset and accidentally stepping on ants, from the ants’ perspective, it’s the same thing. It’s not the intentionality of this little boy who’s trying to kill the ants that matters. It’s the fact that the ants are still getting stepped on, and ants in this case can be a bit of an analogy for humans and human flourishing. It doesn’t require that we be intending to do harmful things in order to actually have harmful effects. That’s one of the main things that came out of this labyrinth in this experiment: good intentions are not enough.

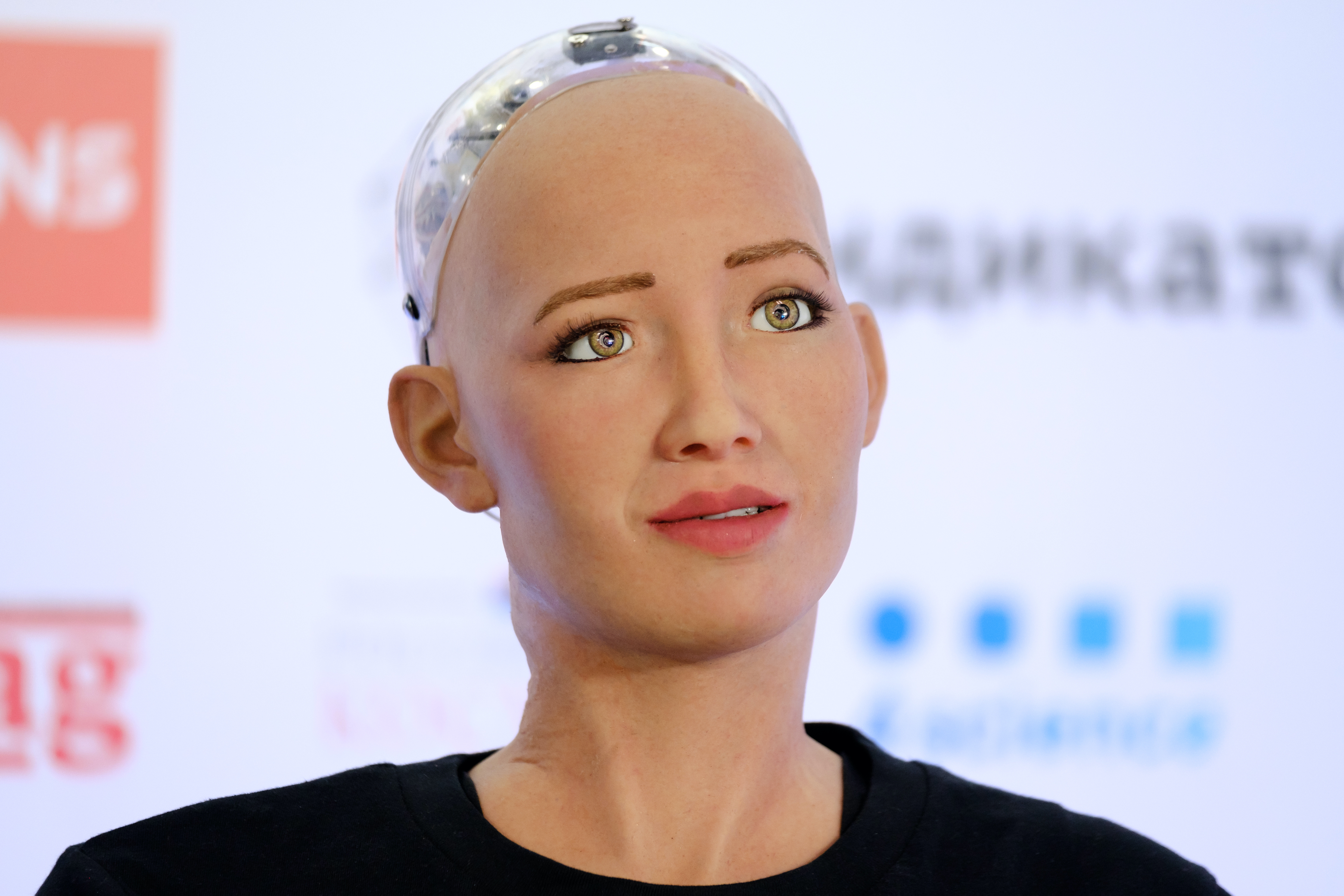

There’s a lot of science fiction that captures our imagination about these super powerful machines, conscious machines and all this kind of generalised AI; it’s really, really far off.

It’s hard to predict with any accuracy when or whether in the future there will be a machine that, whether it’s biologically constructed or constructed out of something else, that has any sentience or consciousness. It’s fun to think about; I don’t think it’s very close. I also don’t know if we’ll know – just like ants don’t really know what we are experiencing. If eventually there evolves, and I do think it would be a kind of evolution, something that is so very advanced, I don’t think we’ll be able to fathom that.

We might not be able to recognise that it’s happening – and this is not to be alarmist. I do think it’s quite far off. There are other challenges with the evolution of technology that are more pressing and much closer, which have to do with the way we’re training these systems on the past. We can’t train them on the future. We’re training them on data sets, and those data sets are derived from the past. So, in a way, they can only replicate or predict in patterns that have already transpired.

Discover more about

Art's questions and the Moral Labyrinth

Newman, S. (Artist). (2019). The Moral Labyrinth [Art installation]. metaLAB, Harvard University.

Newman, S. (Artist). (2020). The Moral Labyrinth [Virtual art installation]. Center for Law, Innovation, and Creativity, Northeastern University.

The Rockefeller Foundation. (2021, February 4). Bellagio Dialogues: Newman. [Video]. YouTube.