Simone Weil was a Jewish French thinker, theologian, philosopher, activist and organiser who was born in 1909 to a middle-class French family, which gave her a very well-rounded education. Her brother was the mathematician André Weil, who was incredibly famous in his own right.

Simone was an incredibly precocious child. She was very well-read; she read Plato and Pascal as a young girl and fell in love with philosophy, but she was also concerned with the state of the world. From a very young age, she showed a tendency that would last her entire life, which was her ability to identify with people who were suffering. When she was six, she heard that people were starving in France and did not have access to food, so she refused to have sugar in her tea as an act of solidarity.

Actions and solidarity

Throughout her entire working life, Simone reflected and wrote about the relationship between our own actions in the world and the solidarity and empathy we might offer others. What is the boundary between those two things? In her own life, she exemplified a very precarious boundary; the way she acted towards others was very much in line with what she wrote.

We often doubt people who write about social justice or contemplate how the world can be better by questioning them: okay, but what do you do in your free time? Are you a hedonist? Do you enjoy having a nice big supper and then writing about labour strife? Simone Weil actually went to work in a factory as a young woman; she wanted to understand what workers were up against so that she could help them and build a world in which equality would be the norm.

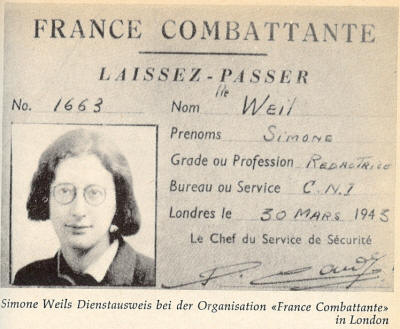

Throughout her life, she got involved in causes – she didn’t just write about them. She went to Spain to fight in the Spanish Civil War, and she tried to get involved in the Second World War. She really saw no boundaries between her own actions in the world and the way she thought of others most oppressed in society.

Social justice and equality

Simone Weil wrote a lot about social justice, but she specifically thought about how we are indebted to one another. As a French thinker, she was very much a product of a rights-based discourse, but she didn’t think in terms of rights because she thought that this would reduce our commitment to each other: we would only think about what we deserve rather than what we owe each other.

She tried to write a declaration of people’s duties. No right has existence in the world without a duty that corresponds to it. If I have a right to something, someone has a duty towards me. Simone Weil tried to shift the focus to duties: we are all obligated to serve justice to each other and to ensure that no one is oppressed, no one is unequal.

Her own understanding of oppression was different to many in her time. She didn’t see oppression as something that can be individually claimed, resting on an individual experience of suffering, but rather something we must all encounter as a human race together. If one person is oppressed, then everyone is implicated in that oppression. She shifted the focus to our debt and our responsibility to each other rather than what we might deserve from the State, or the workers’ movement, or any other organisation to which we might belong.

Simone Weil was born to a Jewish family and received a typical Jewish education. But as a young woman, she started feeling more affinity with the Christian ethos. She became much more mystical in her thinking. It’s fairly certain that she was baptised before she died, and she saw Christianity and Jesus as the only true religion.

She had a very complicated relationship with Judaism. She was one of the first people to use the term “Holocaust” in 1943. But she never saw it as something that must be widely denounced, because why denounce only one genocide when there were a lot of other genocides going on? She had these incredibly critical views of Jews in France, and she herself had to fight antisemitism.

She wanted to work in Algeria, which was then still a colony of France, but she wasn’t allowed to because she was Jewish. She wrote a letter to say: ‘I do not feel Jewish. I do not need to be inhibited by this law.’ It’s very strange – in her philosophy she talked about standing up for the most oppressed, but she never saw Jews as people she must stand up for, even though Jews in Vichy France encountered severe oppression and a lot of things that she saw as problematic.

Towards the end of her life, her philosophy became more and more explicitly Christian. Her last major work, Gravity and Grace, is a work of Christian theology in which she talks about how Jesus and his embodiment of “love thy neighbour” is the real virtue to which we should aspire, rather than other theologies, such as those of Judaism or the Roman Empire, which she was also very much against.

The concept of attention

Simone Weil writes about the concept of attention, which she uses in a different way to our usual understanding of the term. She talks about attention as a way to shift away from the thinking “I”, from the ego, in order to immerse ourselves in the world and accept the void as part of who we are.

By understanding our humility in the world – that we are part and parcel of something larger than us, over which we do not have control – we then become ready to accept grace and be uplifted by a virtue that is larger than us. Attention is a way to empty the thinking “I”.

This idea is in exact opposition to a rationalistic tradition that was prominent both on the left and the right of her time. Socialism sees a thinking “I” as central to bringing the revolution; right-wing ideologies that talk about overcoming oppression, gaining force and the will to power also centralise the “I”. But through the concept of attention, Simone Weil really tries to empty the “I”, to become completely immersed in the world and to accept the void within us.

The individual and the collective

Simon Weil has an interesting relationship with the individual and the collective. On the one hand, she was critical of political collectives, such as political parties and workers’ organisations, which demanded that members submit to their principles. She always sustained the need to be able to think outside of these organisations. Although she was broadly on the left, she was also very critical of socialism. Unlike many of her comrades, she was already critical of Stalinism and of the way that it had been taking hold in the Soviet Union.

But at the same time, Simone also emphasised the need of the individual to be immersed in the world. This goes against the all-important thinking “I” that can conquer and make a piece of land their own. For her, we’re always indebted to the world. We are part of the world, and we are a smaller part of the world than we might think. By accepting this humility, we might be able to do more good because we would be more attentive to the world and the people around us. Her understanding of the individual is so different from both left-wing positions of her time as well as any other right-wing position.

Food and the body

Simone Weil had a complicated relationship to her body and to her identity as a woman. She never felt comfortable with being a woman, nor with her sexual being as a woman. She also had a complicated relationship with food. She often denied herself food when she felt other people were hungry. Her untimely death at the age of 34 in 1943 was brought about either through self-starvation or the exacerbation of an illness that she had acquired throughout the war by not eating.

Simone Weil speaks to a central question: are we entitled to be happy, and to be immersed in our bodies, and to celebrate eating when other people are hungry in the world? For her, the answer was an unequivocal “no”. If there are people who are hungry, then she felt happy to deny herself food. In a strange way, she wasn’t even a martyr because she didn’t suffer pain from that choice. It was a natural consequence of her philosophy, and she was very much at peace with this position.

At the same time, this is a very self-punishing position and one that indeed brought her untimely death. However, her ability to withhold food from herself and her belief that she was not entitled to something that other people were entitled to still sits as a question that haunts us: what do we deserve as human beings? What is our responsibility? Should we deny ourselves basic things because we know other people don’t have them?

Simone Weil is an important but a very uncomfortable role model for women today. One of her most important legacies is the question of the relationship between action and thought. How should we live through the actions that we write about and the things that we believe in? If we write about strife, should we all leave our lives and go and live that life in order to understand it from the ground up? And indeed, what concessions should we make in order to understand how others suffer? Should we all go through various processes of hunger and torture in order to understand what human beings go through?

She teaches us an important lesson about empathy and how we must always be attentive to injustice in the world. But at the same time, her tragic and untimely death teaches us that we mustn’t completely abandon ourselves in the way that she did. You can still be empathetic and live a very dedicated life full of integrity without denying your own humanity, which is what she eventually did.

Women activists through history

Women activists throughout history and still today are those who change history but are often unaccounted for. If we look, for instance, at the 2020 presidential elections in the US and the way that the South shifted to vote Democrat, giving Joe Biden his victory, a lot of these victories were achieved through bottom-up grassroots organisers. Most of them were women; most of them were African American women.

There is this history in which women activists and organisers always do the very boring legwork: knocking on doors, giving pamphlets and talking to neighbours to try to change history. But there are also the women activists who are very conveniently erased from history.

Activism is a problematic concept. I have activist friends who don’t like to use the term “activist” because it feels like you have to activate someone, whereas most of us who work politically know that the process is already there; we just need to be able to listen better. Women activists are the ones who are able to listen and to act on changes in the world. But we must also be much more attentive to them so that we actually remember history in a more accurate way.