The British always boast that the rule of law was invented with the Magna Carta. The idea of the rule of law is that nobody is above the law and that the law applies to everyone. It’s particularly addressed to the powerful – the notion that somehow law might be the way of whipping the ordinary folk into line – but the fact there are people who enjoy impunity was recognised as unacceptable, even when the king tried to have his way. So, the Magna Carta was all about saying to the king, you, too, are answerable to law. It’s now taken as a principle of law around the world, although in some parts of the world, the rule of law is not accepted as it is in developed nations.

Making the powerful answerable to law

Barrister, Bonavero Institute of Human Rights, University of Oxford.

- The Magna Carta was a way of saying to the king, you, too, are answerable to law. It’s now taken as a principle of law around the world.

- The idea that there should be an independent judiciary separate from the State is a vital element in the rule of law – a judiciary that is beyond reproach, that is independent and that makes decisions without fear or favour.

- We can’t remove law from its social context. It’s very important law doesn’t operate in a vacuum. Both international and domestic law are affected by what is taking place.

Making the powerful answerable to law

Photo by Everett Collection

The need for an independent, incorruptible judiciary

Once we agreed that nobody should be above the law, there was a problem over who gets to decide whether there has been a breach of law, especially when it might have been by someone very powerful, like a king, a president, a prime minister or a minister of State. The idea that there should be an independent judiciary separate from the State is a vital element in the rule of law – a judiciary that is beyond reproach, that is independent and that makes decisions without fear or favour.

That element of independence is the real measure of whether the rule of law is operating in a country. There are places that insist that they are operating the rule of law, but when you look closer, you see that the judiciary is not independent, that there aren’t independent lawyers and a legal profession that will stand up on behalf of those who are critics of the State or of the government, journalists who expose corruption or whatever. An independent legal profession is another element absolutely essential to the rule of law.

How can we keep the judicial system independent?

The judiciary should be well enough paid that they’re not going to be corrupted by offers of money to make a decision one way or the other; offers not just from the State but from interests within a State, for example very wealthy business people or the mafia. The business of corrupting judges is one of the things that always has to be addressed.

It’s important that judges are appointed in independent ways. It took a bit of arguing for, here in the United Kingdom, but we have the Judicial Appointments Commission now. Before that, it was the Lord Chancellor who ultimately made the appointments to our highest courts. You really do need an independent appointments method to find some mechanism for choosing those who have integrity, those who have little reason to be corrupted, those who are not parti pris and who have become experienced in the business of independent decision-making, and this usually involves proper training processes.

Now, in the common law system, the judiciary is usually appointed from the practitioner lawyers. In Canada and in Australia, the appointments processes draw upon practitioner lawyers who’ve had lots of experience in the court and then move them into higher judicial offices, while giving them proper training and opportunities to help to develop their skills as judges. In other systems, like the civil law system, people can study law and then decide to do the training to become a judge when they’re in their late 20s. They then start at a lower level than the judiciary and work their way up through the system.

The key to curbing corruption

Photo by Andrey Burmakin

Different nations have different ways of creating that judiciary, but the important elements are to protect them from easily being removed. There has to be some sort of security of tenure so that you can’t have someone taking issue against a particular judge because of decisions that they are making and then having them removed from office. It has to be very difficult to remove a judge. That way you maintain their independence. They know that they’re secure in their position and that allows them to make decisions which may be unpopular with the government or unpopular with sections of society, but they do it true to their oath of office. So, you create protection, you pay them properly, you allow them to be a separate entity and you protect that separation of power. They have great power in society, but it’s separate from that of those who are elected.

Lawyers: more than just hired guns

The important thing for lawyers is that they mustn’t feel that they’re simply there as a hired gun. There are certain rules of professionalism – you don’t invent defences for people. When someone says to you, I’m guilty but I’m going to tell lies and pretend that I’m not guilty, you have a duty in law and a duty as a professional lawyer and barrister to say, I’m not able to act for you because to do so would be to be complicit in dishonesty. There is a whole set of rules about how you function as a lawyer. The integrity of lawyers has to revolve around the idea of a first principle that you are a protector and safeguard of the law and of the independence of our legal system.

One of the things that we’ve been debating in the United Kingdom recently has been the limits of one’s role as a lawyer outside of one’s own nation. We operate something called the cab rank principle, and that is one of the things that helps people understand the importance of the independence of lawyers.

Safeguarding, not sabotaging the system

In my years of practice, I’ve done many cases which have been abhorrent to the general public. I’ve acted in cases involving allegations of terrorism, where explosions have taken place or where there have been conspiracies to cause explosions, where my clients have been hated for the organisations that they belong to. I’ve acted for people who’ve been accused of murder or a violation of other human beings. All of that could very easily make you someone that the general public thinks of as a terrible person. But, of course, the answer to that is that, as lawyers, we’re actually protecting the system and acting for whoever we’re asked to act for, if we’re available and if we have the expertise in that field of law, and we do it on the basis that it’s protecting the system.

We call this the Erskine Principle. In the 18th century, Tom Paine, who was a great champion of human rights, wrote a pamphlet called Rights of Man. He was brought before the courts for sedition, for championing something that was going to bring down the State, and he fled to France, where a revolution was in the offing because people wanted rights. He was put on trial in his absence and a very distinguished lawyer called Erskine stepped forward and represented him. Erskine was excoriated for doing so by his political confederates, who would be considered very conservative people today. He said, no, I am doing this because we have to make sure that people with whom we don’t agree are properly represented in the courts and defended, and that freedom of speech is protected, because that is what makes for a decent society.

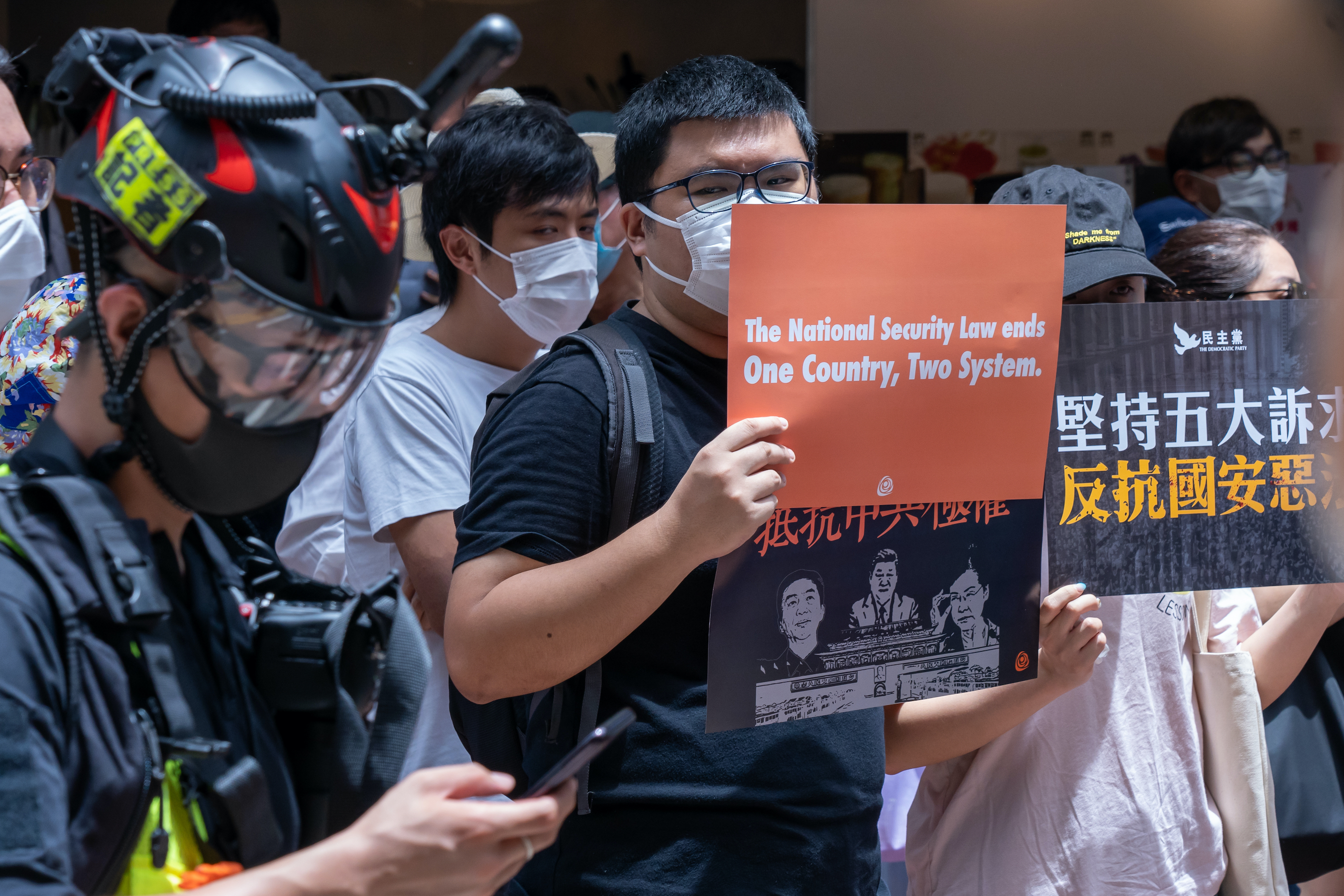

Why is the rules-based order under threat?

Photo by Jimmy Siu

You can’t remove law from its social context. It’s very important that law doesn’t operate in a vacuum. Both international law and domestic law are affected by what is taking place. Populist governments say to people that what we need is tougher law, to imprison more people and to build more walls, to keep people out. Simple solutions are presented which involve huge erosions of the rights and protections that we had been developing in a rules-based world. International law has been created over the treaties and over many centuries. A great moment of change came after the Second World War, where the injection of a moral basis into international law took place: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights conventions to protect refugees, to prevent statelessness and to prevent torture.

Those conventions were embraced by a world thirsting for a higher moral sense. Unfortunately, that rules-based order is being dissolved because of populism and because of a lack of commitment to those important principles. When you make your supreme-value money, it’s inevitable that you will get corruption in legal systems and within governments. I’m afraid you even get it amongst lawyers who become a hired gun and basically forget the ethics that have informed our professions around the world for so long.

Discover more about

rules-based order

Kennedy, H. (2004). Just Law: The Changing Face of Justice – and Why It Matters to Us All. Vintage.

Kennedy, H. (2004). Legal Conundrums in our Brave New World (Hamlyn Lectures). Sweet & Maxwell.