This question is one that I have wrestled with a lot, in part because it’s fairly unconventional for academic philosophers to write biographies. There are some notable exceptions, but it’s often not considered a philosophical enterprise to write the history of a person’s life. In the philosophy of biography, there are two opposing camps: on the one hand, you get compartmentalists, who say that a life is irrelevant to the interpretation of the work and vice versa. On the other hand, at the other end of the spectrum, you get the idea that the person’s life is going to be a key that unlocks the understanding of their work. They might even go so far as to say that you will not understand the work of that philosopher unless you know about the context in which they lived, and so forth.

A brief biography of Simone de Beauvoir

Tutorial Fellow in Philosophy and Christian Ethics

- For Simone de Beauvoir, there was ‘no divorce between philosophy and life’; she believed that each living step was a philosophical choice.

- Beauvoir saw the interaction of class and gender in her mother’s life and in her father’s life. She grew up in the changing circumstances that were widespread for women at that time, after World War I.

- When Beauvoir wrote her autobiography, she was accused of being vain and self-centred. This demonstrates some of the dynamics that she thought were operative in women’s oppression and exclusion from public discourse.

Should we read biographies of philosophers?

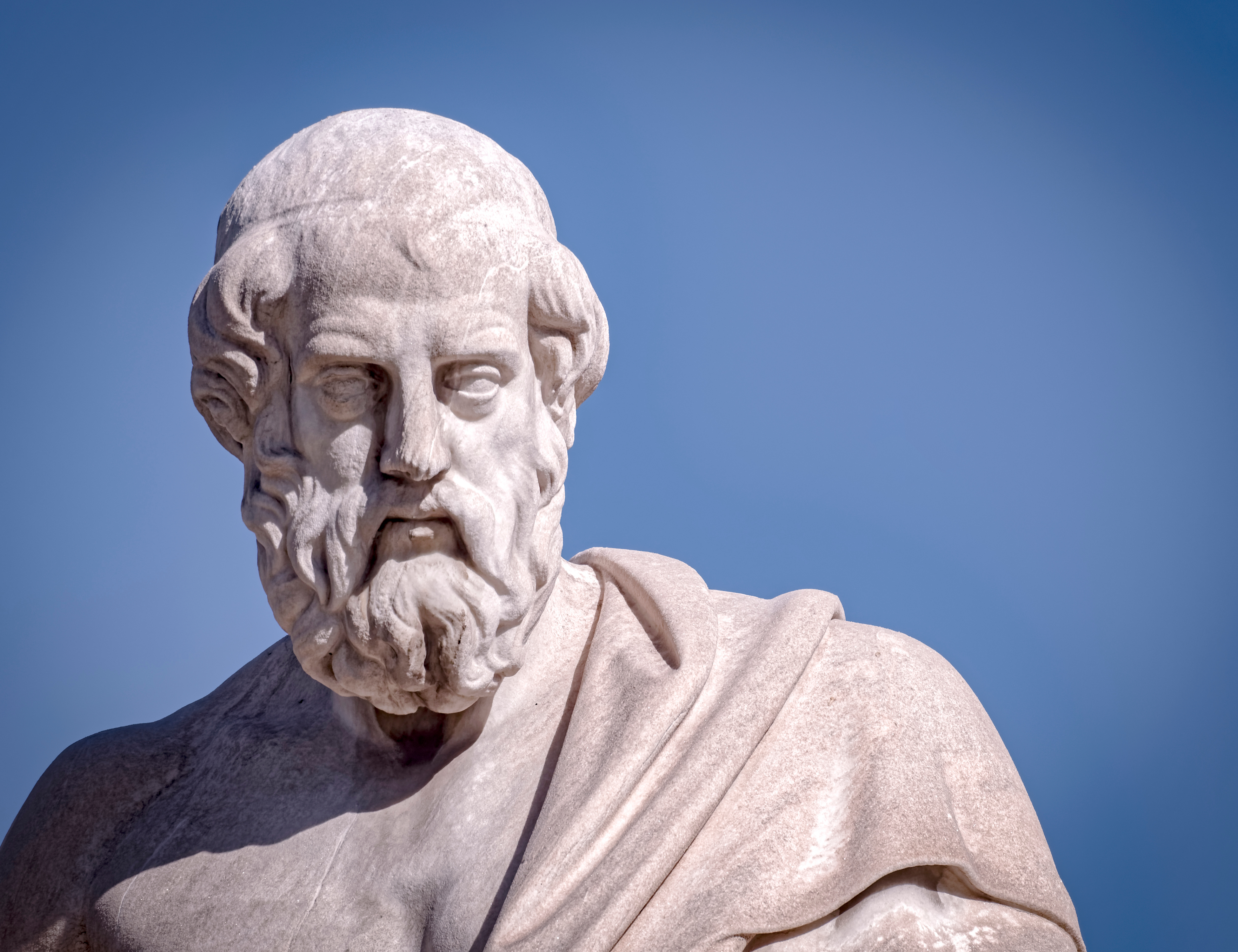

Photo by Dimitrios P

How to approach philosophers’ biographies

I don’t think that there’s a general answer about what the right way is to approach philosophers’ biographies. I think, in some cases, people’s lives are not very relevant to their work. It doesn’t really help me understand the philosophy of Kant, for example, to know that he went for a very regular walk every day in Königsberg. My view is that the relation of life and work depends very much on the particular philosopher. In Beauvoir’s case, I think it’s very valuable to understand her life, because she was a philosopher who claimed explicitly that there was ‘no divorce between philosophy and life’; she thought that each living step was a philosophical choice. She belongs to a tradition that calls philosophy a way of life, and if you look at certain ancient philosophies, it was seen to be not just a legitimate, but a particularly helpful way to look at philosophy to try to approach it biographically. If you look at the life of Socrates, for example, the idea is that we can learn something valuable about living a human life by studying the examples of others.

A sexist perspective of Beauvoir’s life

Beauvoir’s life has often been received in a sexist way, and her work has often been received as derivative work. Moreover, focusing on her in her relation to Sartre, whether intellectually or romantically, plays precisely into one of the dynamics that she called out as problematic in The Second Sex. In the book, she said that what is proposed to women very often is that her life will be defined by her love. Beauvoir’s life has frequently been recounted as a great love story of the 20th century; there are chapters in books like How the French Invented Love that describe the relationship between Sartre and Beauvoir – but the way that this relationship has been romanticised isn’t very faithful to the facts. It’s also not faithful to Beauvoir’s own philosophy of becoming a woman. In fact, it’s quite ironically opposed to it.

A traditional upbringing

Beauvoir had a traditional bourgeois Catholic upbringing. Her family had been relatively wealthy, but her father was the second son, so was not to inherit as much as his elder brother. He invested his money in pre-revolutionary Russian stocks, which then lost all their value, so, in her childhood, she went from having the expectations of a young woman who would have been married off with a sizeable dowry, to someone who’d had to move into a much smaller apartment and not have live-in help, for example.

She saw the interaction of class and gender in her mother’s and father’s lives. She grew up in these changing circumstances that were widespread for women at that time, after the First World War. Her father wanted her to have an education. She loved philosophy, and she wanted to study, but her parents saw it as a source of shame that she needed to earn her own living, and they were very concerned about trying to maintain as much status as they could, given all the status they had lost. Beauvoir really struggled, in her childhood, with the expectations that others had of her and the feeling that she had to be unfaithful to herself in order to conform with those.

Falling in love with philosophy

She studies philosophy, and she begins to see that in the philosophical method, there’s a kind of doubt which is a very productive kind of doubt. It’s not self-doubt of the kind that self-help books might tell us to rid ourselves of, it’s this very valuable, reflective way of looking at what you value for yourself. So, she starts to fall in love with philosophy, to think about what kind of ‘self’ she is and what kind of ‘self’ she wants to become.

Very early on, Beauvoir starts to raise the question of love, and how love is used to legitimise the sacrifice of women to other people’s projects and to other people’s benefit. In the late 1920s, she studied these kinds of questions. She wrote her master’s thesis on ethics and discussed questions of love in ethics, including the Catholic love command that you should love your neighbour as yourself. She also worked on the concept of the personality in Leibniz, which is the central thing that makes you who you are. When she’s doing this, she meets a young man named Jean-Paul Sartre.

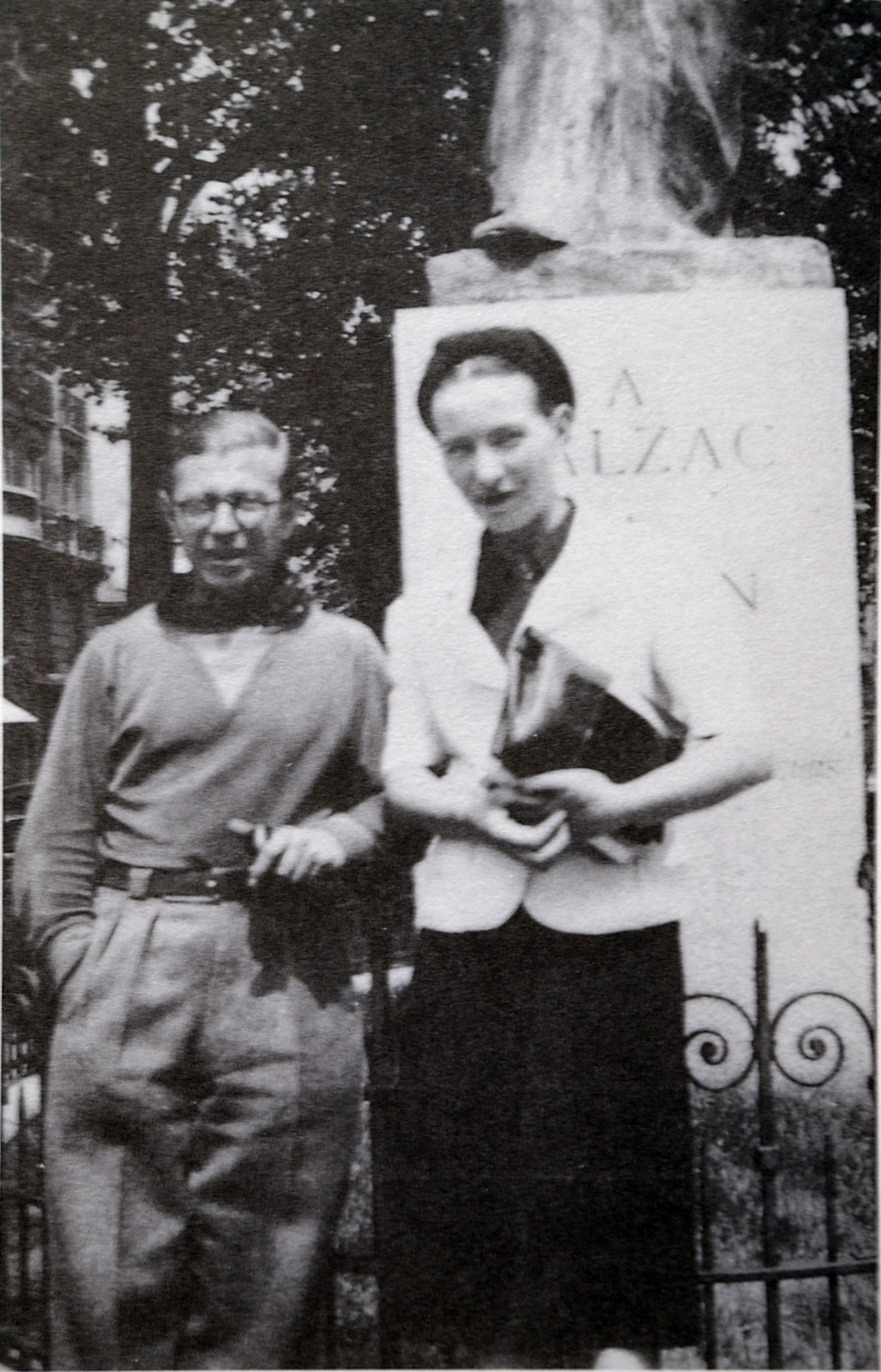

Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir at Balzac Memorial. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Beauvoir and Sartre’s relationship

In her memoir, she famously claimed that they had decided that they were necessary in each other’s lives, but that it was possible to have contingent loves on the side. So, their relationship has been regarded as a combination of two things that many people want, both freedom and fidelity. It’s also been heralded as a precursor of the open relationships or polyamory that are more common – or, at least, more widely acknowledged – today.

But Beauvoir did not write all of her contingent loves into her memoirs. She did write Nelson Algren into her story, but the kind of legend of the necessary relationship made it possible for people to think that Sartre benefited from this open relationship in ways that Beauvoir did not. However, in the last several decades, material has come to light, showing that, actually, within a decade of Beauvoir and Sartre forming their relationship, Beauvoir had ceased to have any kind of sexual relationship with him and had multiple other partners.

A romantic relationship?

As I see it, the relationship is not best conceived as a romantic relationship, if by that we mean a relationship in which sex plays a big role. She actually says, in the 1920s, that Sartre’s place in her life was not in her heart or in her body; she said, ‘Many others could be, but he is the incomparable friend of my thought’. So, they had a very intense and close intellectual relationship, and they did love each other, but their love wasn’t like the stereotypical love people have assumed due to heterosexual tropes in the 20th century about what love is. In fact, it is the case that within a decade, Beauvoir had had relationships with Jacques-Laurent Bost and also with several young women.

Omitting facts in her memoirs

One of the things that’s fascinating, comparing her life to the version of her life that she recounted in the memoirs, is how many things she left out and why she left those things out. I think there are different ways of looking at this. On the one hand, you could say she was trying to present herself more favourably than she would have if she’d told the truth; however, there’s also the question of what we should expect of public figures in terms of how much of their private lives they share. In the Instagram age that we live in, it’s difficult to imagine just how much she was sharing in 1958, when she said as much about her life as she did.

Women’s exclusion from public discourse

Writing an autobiography is not new in philosophical practice. Rousseau wrote his Confessions, Augustine wrote his Confessions. Those works are considered philosophical works, which can speak to us across time about the human condition. When Beauvoir wrote her autobiography about becoming a woman, about the experience of aging, she was accused of being vain and self-centred. I think there’s something in this which says that when a woman attends to her own experience, when a woman attends to her discomfort with aging, that’s vanity or attention-seeking, instead of reflection on what it means to be human. So, this is another reason why it’s really valuable to look at Beauvoir’s life in relation to her work, because the reception itself demonstrates some of the dynamics that she thought were operative in women’s oppression and exclusion from public discourse.

Discover more about

Beauvoir’s life

Kirkpatrick, K. (2019). Becoming Beauvoir: A Life. Bloomsbury Academic.

Kirkpatrick, K. (2019). Beauvoir: Interview with Kate Kirpkaptrick. Philosophy Bites.

Warburton, N. (2019). The Best Simone de Beauvoir Books recommended by Kate Kirkpatrick. Five Books.