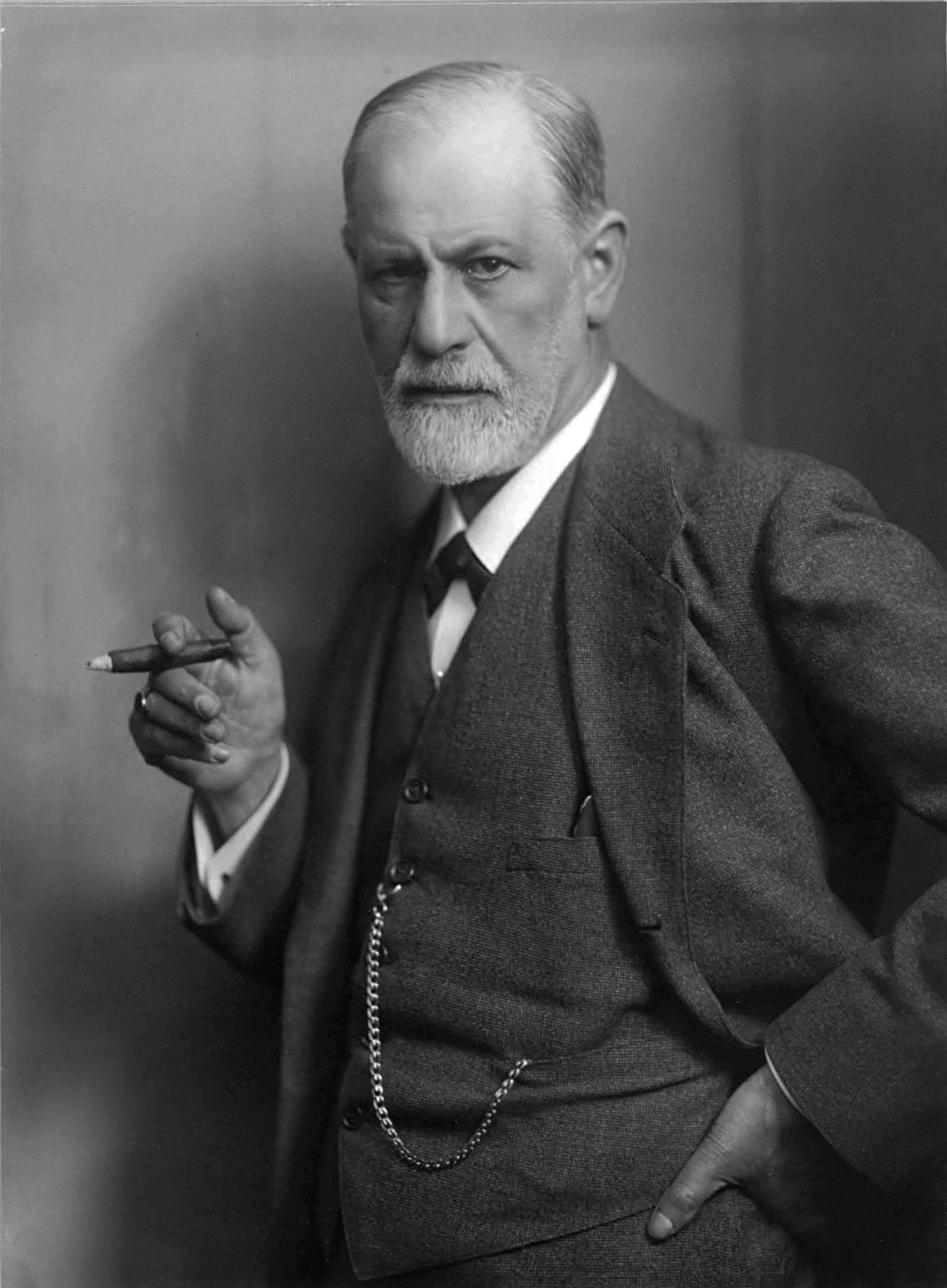

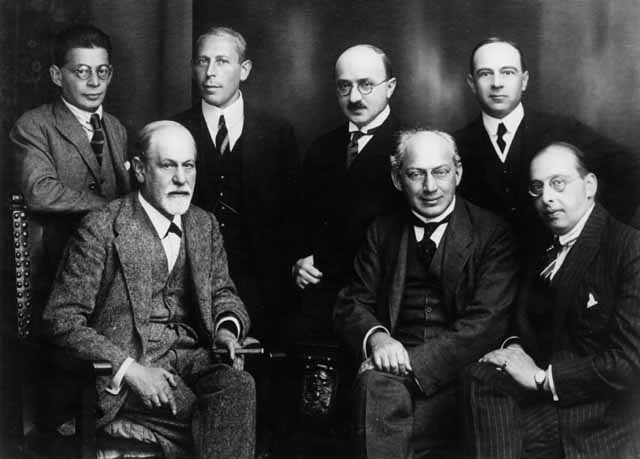

There’s a long history of psychoanalysis’s involvement in politics, which really begins with Freud – but that history is both controversial and mixed. On the one hand, you could see Freud himself as a sort of traditional liberal bourgeois with quite a conservative mentality. It’s true in his treatment of the women in his life. It’s true also in many of his attitudes towards such things as social revolution, Bolshevism and the possibilities of there ever being a truly liberated, emancipated world. He was always very cautious about that.

Some of the conservatism that you find in Freud himself is also reflected in the development of psychoanalysis as a kind of individualised, liberal-minded but nevertheless constrained bourgeois practice, in which people are seen one by one, normally in private practice outside public health systems. Over the course of the last century, people were often treated in line with a number of quite regressive social norms, particularly in relation to women. Ideas about what women’s “true” function might be, for example, pervaded psychoanalysis until at least the 1980s.