In conjunction with this very unhealthy environment, he develops lung disease. This, too, defines his childhood, as does his dreadful medical treatment – medically dreadful, but also emotionally dreadful. As a young man, he is placed on a ward for the palliative care of the dying and spends weeks and weeks just watching people die. These experiences of illness, abuse and deprivation eventually give rise to his sensibility as a writer.

Putting anger into words

Psychoanalyst and Professor of Modern Literary Theory

- The 20th century gave rise to angry writers from across the political spectrum.

- Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard expresses disgust with the lowness of human behaviour while also valuing the singularity of human beings.

- African American writer James Baldwin uses anger as one of the great drivers of his writing; he says that if we don’t want to become the prisoners of our own rage, we need to recognise that there is more to human interaction than just the facts.

A traumatic childhood

In the middle of the 20th century – an agitated century defined by trauma and turbulence – you see a number of very angry writers from across the political spectrum. You see a writer like Louis-Ferdinand Céline, who writes novels in the forms of rants: long howls of rage and disgust. However, the writer who most interests me in this vein, and who in some respects is not unlike Céline, although with a cooler anger, is the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard.

Bernhard grew up during the war in Austria and had a very traumatic childhood. He experienced poverty; he experienced the depredations of Nazi rule; he was forced to go to Nazi youth movements and to a boarding school run by a petty Nazi regime. This cultivated in him a singular disgust and disappointment in the possibilities of the human being: a sense that there were no expectations low enough once you’ve grown up in the shadow of Nazism; no depths low enough for human beings to stoop to.

Bombed buildings along the Franz Josef Wharf in Vienna. In the foreground, the Maris Bridge is undergoing repairs. 1946. Everett Collection.

Putting anger into words

Bernhard puts on plays which are cries of provocation, where he’s really trying to tell his native Austria just what he thinks of it. The most powerful expression comes in his novels, which almost all take the form of single unbroken paragraphs in monologue, in which one speaker rails or rants against the world and tells us a story which usually involves humiliation and an expression of laconic disgust.

He’s cooler than Céline. He’s not screaming, but in a rather world-weary voice, in the same repeated phrases, in the same patterns of speech, he tells us about the general lowness and shabbiness of human behaviour. As for our illusions about the height of human morality, the height of human cultural achievement, he’s sceptical about all of this.

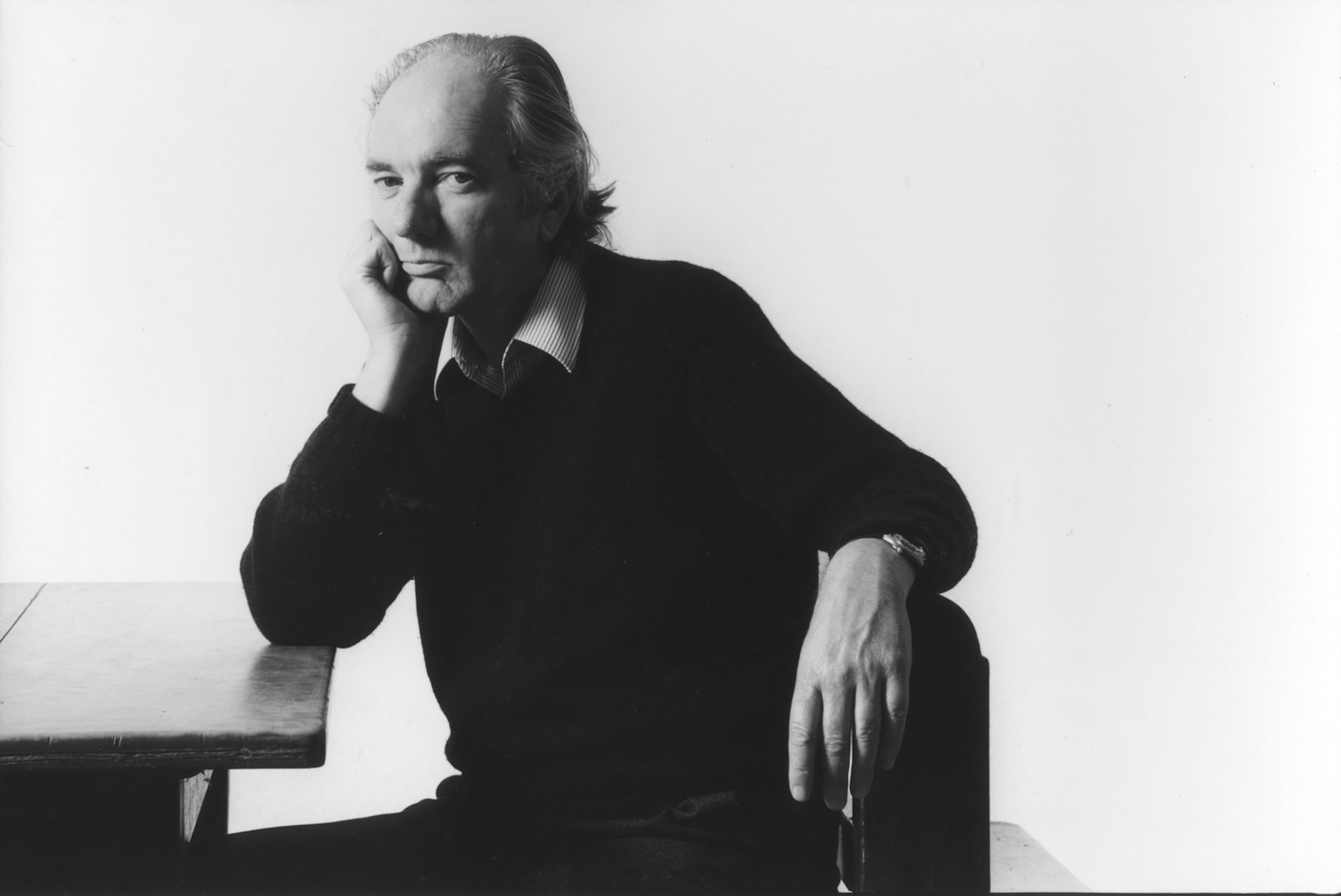

Austrian author Thomas Bernhard. Owned by Monozigote. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Singularity of the human being

There is another current which people often don’t notice in Bernhard. In the midst of this, he will find a way to tell us, through his speaker, that he’s not simply saying this in the name of disgust and horror at the hopelessness of the human race, but in the name of what he thinks of as the singularity of the human being, which is a very important principle in psychoanalysis as well.

When we abuse and collectivise and homogenise human beings, when we turn them into indifferent, fungible, interchangeable cells, we do violence to their singularity as human beings. Bernhard is a spokesman for the loss of singularity, particularly under the worst political regimes of our time under fascism.

If writing is worth doing, it’s because it gives some expression to the singular human voice. Whatever you think of Bernhard, he certainly has a very singular voice.

Anger as a driving force in Baldwin

Writing at almost the same time as Bernhard, between the 1950s and the 1980s, but on the other side of the Atlantic, is the great African American novelist and essayist James Baldwin. Baldwin also makes anger one of the great drivers of his writing. In his novels, many of the characters are so broken by anger that they’re unable to discharge or express a sense of burning injustice for which there is no redress in the racially divided society of the US in the 1950s, 1960s and onwards.

Baldwin, though, relates differently to that anger. We see an example of it in some of his essayistic writing on the Nation of Islam, on what he calls the Black Muslims. Baldwin says that if all you were interested in was the evidential case for the anger of the Black Muslims, you would have to join them. You couldn’t argue with them, because everything they say about white America, everything they say about racial injustice is, as a matter of fact, true. You would have to hate white people; you would have to become a separatist; you would have to feel that there is no future in interracial relations, in integration, in worldly harmony.

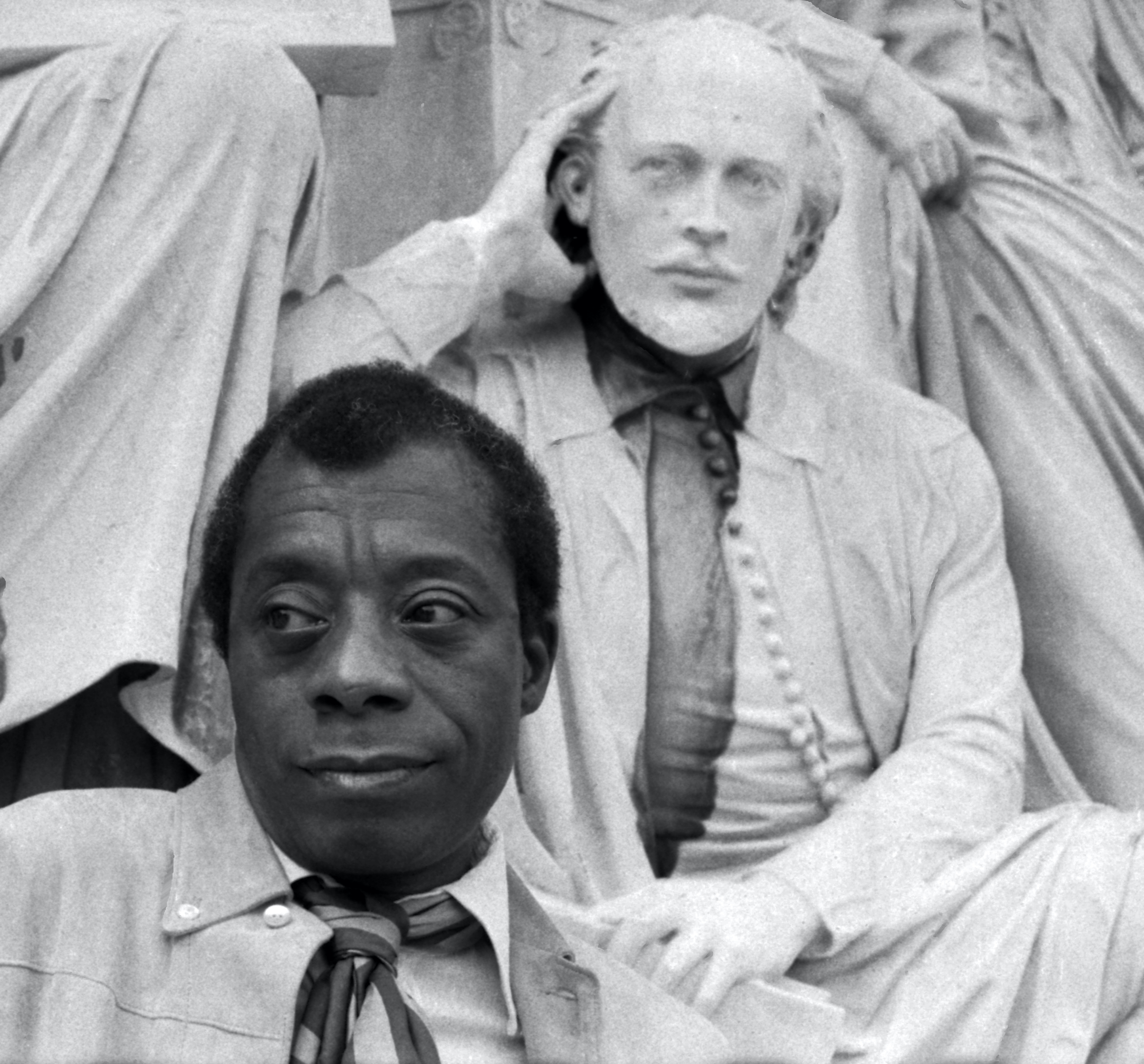

Portrait of James Baldwin with the statue of Shakespeare. Albert Memorial. Photo by Allan Warren. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Prisoners of our own anger

Baldwin’s point is that if we don’t want to become the prisoners of our own anger and rage, if we don’t want to be deformed by it, and this is true for white and Black alike, then we need to recognise that there is more to human life and to human interaction than the evidence, the facts. If you have an understanding of human emotional complexity, you see that what he calls the cruelty and the arrogance of white people is also pain and bafflement and – this is a rather beautiful phrase in the context – basic decency.

That’s what he says: underneath their cruelty and arrogance, there is a kind of basic decency which is invisible. If you took the facts on their face, you wouldn’t be able to see it. It requires us to take a leap of faith to see common humanity and common basic decency. Not in a sentimental way; it’s a tough stance to take, actually, and that’s what he’s saying. It’s a use of the anger and rage at the cruelty that African Americans were facing every day of their lives, but it’s mobilised to ensure that you can see a way beyond it, rather than become its prisoner.

Discover more about

angry writers

Eigen, M. (2002). Rage. Wesleyan University Press.

Ngai, S. (2005). Ugly Feelings. Harvard Uiversity Press.