He was a strong defender of the revolution, right from the very beginning. He identified with it and he often claimed to speak on the part of the people. The trajectory of Robespierre’s life is so dramatic, because he moved from that very progressive position to being the person who is most often blamed for the excesses of the revolutionary terror.

From progress to excess: The revolutionary life of Robespierre

Lecturer

- Robespierre was a very strong defender of the revolution. He was committed to the revolution to the point of obsession.

- The whole movement was caught up in a collective hysteria, in trying to understand who was a friend and who was an enemy.

- The idea that Robespierre must be somebody to be supported or vilified changed around the time of the bicentenary of the revolution, in 1989.

A defender of the revolution

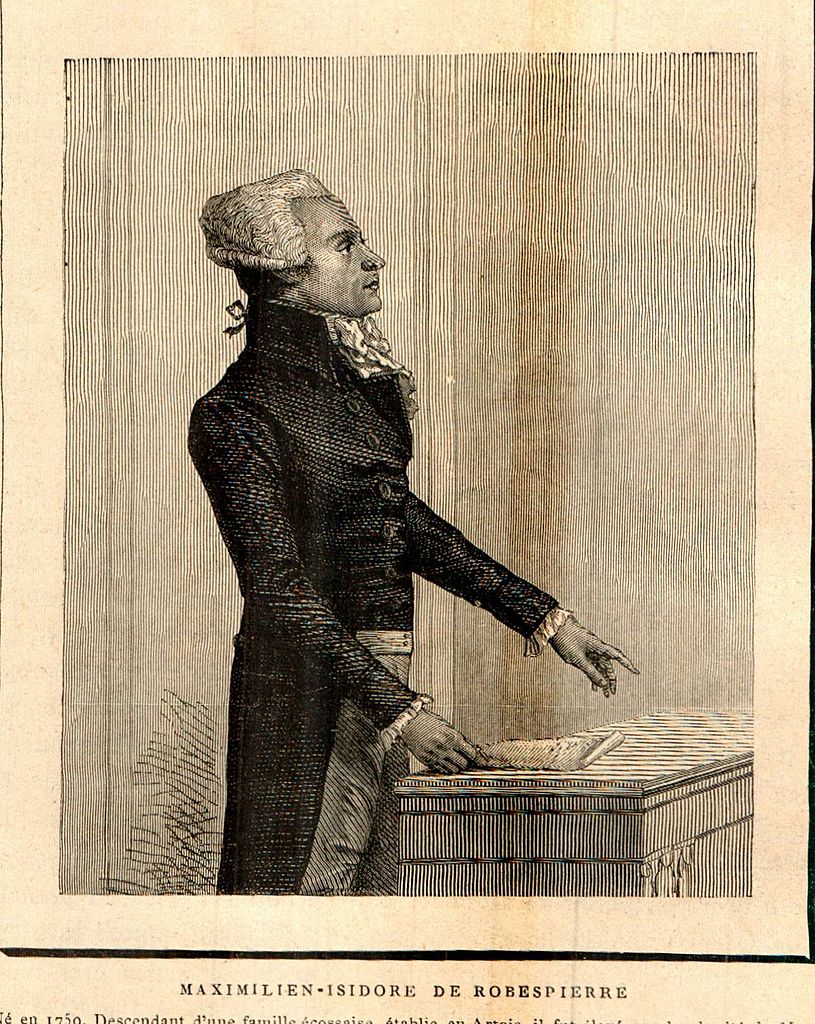

Robespierre was a lawyer from Arras. He came from a modest, relatively impoverished background and he was elected as a representative to the Third Estate in 1789. When he found himself in the position of being able to contribute to the constitutional debates that took place, he increasingly became a voice for the progressive revolution. He was an early and strong defender of the Declaration of Rights – and of the extension of those rights to certain excluded groups, for example Jews and actors.

Robespierre was an early advocate of the people’s opportunity to survey the debates that were happening on their behalf. He wanted to increase the number of spectators who could be present during those events, in almost an early idea of televising parliament or allowing the public to have scrutiny over what is happening in those debates.

Portrait of Maximilien Robespierre. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

A fanatical identification

Robespierre makes an early, very powerful, personal commitment to the revolution. This partly works through rhetoric: he often claims to be speaking on the part of the people and to have access to the will of the people, and he develops a reputation for being very pure in his political commitment. One of the reasons for this is that he doesn’t have anything to counteract his commitment to the revolution, once it begins. He is completely committed to the political project, and he becomes almost obsessed with the idea of corruption. He sees corruption everywhere. His revolutionary colleagues are open to advancing themselves. They remain interested in making money. They’re interested in sex. They’re interested in power. Robespierre takes a very different view. He becomes more and more censorious of those people because he himself experiences almost a fanatical identification with the revolution.

Friend or enemy?

The whole movement is caught up in the problem of trying to identify who is genuinely supportive of the revolution and who is hoping to subvert it, and that problem becomes more and more extreme as the country descends into a civil war, and as it also becomes involved in a foreign war. There is the idea that there are people pretending to support the revolution, pretending to embrace its principles and pretending to hope to secure the future of the republic. Then there is the paranoid suspicion that one’s closest colleagues, neighbours or friends might actually not be as committed to the project of the revolution as you are. Robespierre becomes a very powerful dynamic, and, as a person, he embodies it. Yet, it’s not limited to him. There is almost a collective hysteria in trying to understand who is a friend and who is an enemy.

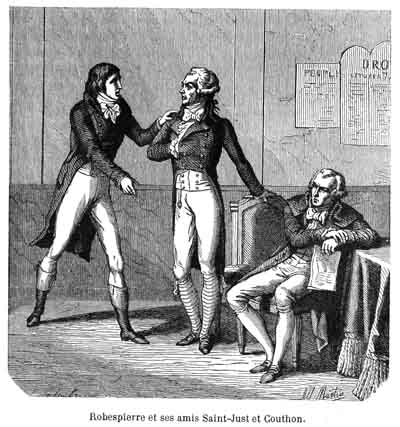

Triumvirate of Robespierre, Couthon and Saint-Just, 1794. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

An extreme obsession

Robespierre’s obsessive personality will always be one of the great mysteries at the centre of the revolutionary drama. Obviously, there were other lawyers, other friends and other revolutionaries who had strong commitments to the events, but he goes to a different level of commitment. Robespierre has almost no personal life. He has a seemingly priest-like commitment to the revolution and, as a young man, only has his life to lose – and he’s prepared to lose it in the revolution. For him, that is an index of the purity of his commitment.

This is a story about idealism and fanaticism. It can help us to understand the way in which a young person can become completely swept up in a political ideology to the point of being prepared to sacrifice their own life and perhaps, more importantly, other people’s lives.

Robespierre without the revolution?

Thinking about Robespierre’s life without the revolution is very interesting. Personally, I think he would have stayed in Arras. He would have become an upright, prominent lawyer, taking on important local cases. He would probably have married and had a family. He would have been a good lawyer, under the old regime. It was the revolution that gave him the opportunity to have an absolutely extraordinary life.

There’s one other counterfactual vision of Robespierre that I find very interesting, which I discussed with the historian Norman Hampson. What would have happened if Robespierre hadn’t fallen when he did? What would have happened between him and Saint-Just, his revolutionary colleague? Would there eventually have been a falling out between the two of them? How long would they have lasted in their friendship and in their shared ideals?

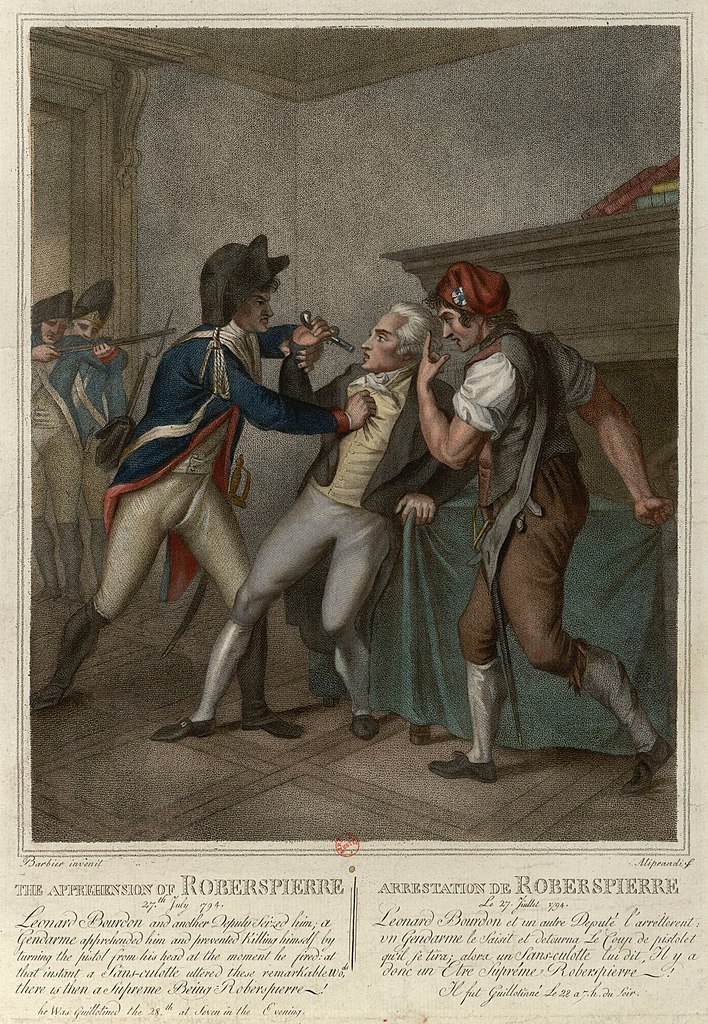

The apprehension of Roberspierre: 27th July 1794. Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

The story of Robespierre’s life is one of, in sequence, turning against the people who had been close to him at earlier stages in the revolution. My view is that Saint-Just would have triumphed over Robespierre in the end, because he was even younger and, in many respects, even more extreme in some of his ideas. I think that would have been the dynamic of the falling out between them both, but the really interesting question is how long that would have taken and what might have happened in that period of time.

Trying to understand Robespierre

The strongly politicised history of Robespierre’s life, the idea that he must be either a friend or an enemy, somebody to be supported or vilified, changed around the time of the bicentenary of the revolution, in 1989 – perhaps, before that. Ever since then, it has been possible to understand him, to put his ideas and his decisions into the context of the revolution in an informed and rich way so that we can try to understand its dramatic trajectory. How is it possible to begin as a progressive revolutionary defending the universal rights of man and citizen and then end as the person most identified with the terror?

Discover more about

Robespierre

Scurr, R. (2007). Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution. Vintage.