Even so, there are reports of Napoleon taking a great interest in that garden. On one occasion, some visitors arrived while he was watering some new flower beds that had been put in. Clearly, it was something that he derived enormous enjoyment from. When he renovated the palace at Fontainebleau, he specifically asked for a spiral staircase to be put in that would connect his library to his private garden so that he could go into it in the middle of the night, if he wanted to.

The imperial gardener: at home with Napoleon

Lecturer

- I’ve tried to understand Napoleon as a real person, as somebody who interacted with other people and with the natural world.

- Once he’s in power and he has the opportunity to think about urban planning, Napoleon is preoccupied with trying to have green spaces at the centre of the cities he has conquered.

- The fascination of Napoleon’s life is the extraordinary trajectory from gardening in Corsica, to being an emperor and then to being an exile, finding solace in trying to make one last garden.

A great man or a villain?

The debate about Napoleon has long been caught up in the question, is he great or is he a villain? It is very polarised territory. He has fierce defenders and fierce detractors, and they constantly return to the question of whether he is the greatest ever man, or whether there are greater men than him.

I’m not alone in thinking that what we really need to do is to try to understand Napoleon, not to be engaging in some almost game-show-type voting for him or against him. Interestingly, even very serious historians find it difficult to move definitively away from those questions. They come back at conferences, they come back in biographies and they come back in documentaries – the question, is he great?

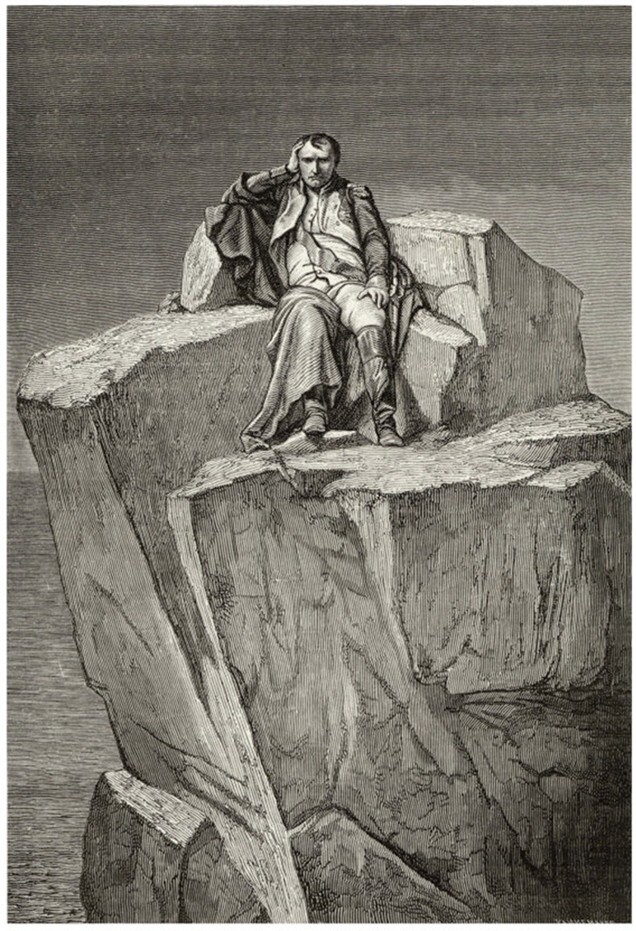

One of the reasons for that is because Napoleon set up his legacy in those terms when he was in exile on St Helena. When he was thinking about his life and dictating his memoirs, he matched himself against Julius Caesar. That was the way he wanted to be remembered. In many respects, that is the way he has been remembered.

Napoleon on Saint Helena. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Understanding Napoleon

To try and move away from this question, I have approached his life from a completely different angle. I’ve tried to understand him as a real person, as somebody who interacted, throughout his life, with other people and with the natural world. I don’t deny that he was an extraordinary person – clearly, he was an extraordinary person. What I’m interested in doing is trying to capture how it was for more ordinary people, in more ordinary settings, to interact with him. Certainly, some of those settings that I have been focusing on involve his interactions with the natural world.

Nature and revolution

Throughout his life, Napoleon interacts strongly with the natural world. He has a deep love of nature. As almost everyone knows, he was born in Corsica, and spent a lot of his youth there. One of the first episodes in his early life that I have focused on is his attempt to have a mulberry nursery in Corsica: his father took a loan from the French State, but the mulberry nursery failed. In the aftermath of Napoleon’s father’s death, the French State recalled the loan and almost bankrupted his family. So, when the revolution in 1789 began, the question for Napoleon was what does this mean for Corsica and what does this mean for my family’s loan? So, there is an example of how located his concerns are. He has no real commitment to the old regime. The revolution is an opportunity for him. In the very specific context of his family and where he was born, he is open to the idea of revolutionary change.

An opportunity to advance himself

Napoleon is a good lawyer, and an excellent soldier. He is at first undecided as to where his future will be. Will it be in Corsica? Will it be back in France, where he had been at school? What he falls back on is his career and his opportunity to advance himself in those wars, which continue for a very long time. He is helped by Robespierre’s younger brother and is fortunate not to be caught up in the fall of Robespierre. So, at the very beginning of the revolution, Napoleon is certainly open to advancing himself through the opportunities that it is bringing.

Napoleon Bonaparte’s birthplace, Ajaccio House, Ajaccio. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Napoleon’s urban planning

In the early revolutionary period, Napoleon is very fond of the Jardin des Plantes, where he goes with his friends. It’s interesting that it’s one of the very institutions that survived the revolution: partly by being reconfigured, partly by some very clever decisions on behalf of the botanists and the scientists.

Napoleon is very interested in the scientists and the botanists in that early period. As he becomes drawn deeper and deeper into politics and into warfare, he has a more remote relationship to various natural places, natural gardens that he passes through, but once he’s in power and he has the opportunity to think about urban planning – not just in Paris but also in Rome, Venice and other places that he has conquered – he is preoccupied with trying to have green spaces at the centre of those cities. Once he’s in exile on Elba, and afterwards on St Helena, the opportunity to garden comes back into his life and it becomes almost a poignant attempt to continue to impose his very strong personality, his very strong will on the shrinking amounts of territory that remain available to him.

Two contrasting realities

The mystery and fascination of Napoleon’s life is the extraordinary trajectory from being a person who is, basically, gardening in Corsica, a relatively ordinary young soldier, to being an emperor with command over vast amounts of territory and people’s lives, and then falling back again and becoming an exile, a captive, somebody under house arrest until they die, and at that point, him finding solace in trying to make one last garden.

For me, there is a great poignancy in the story. It encompasses the legend, the conqueror and what he wanted to project to posterity, but also the reality that, at the end of the day, he was a real person, a real man with a fragile human body. And he came to an end in a specific place at a specific time.

It’s a very extreme trajectory. It covers much more ground. It’s an extraordinary contrast that the arc of a single life can span such different places and such different realities for that particular person.

Identifying with Napoleon?

I think that the great question of whether Napoleon was a great man is most interesting to historians and to readers who in some respects identify with him. In defending Napoleon as a great man, there is perhaps something in themselves that they are projecting onto him. He is the ultimate example of a self-made man. He comes from nowhere and he becomes the emperor. So, there is always going to be an attraction for people who are interested in that kind of opportunity, or who are drawn in by the idea that Napoleon was able to achieve so much, coming from such a relatively obscure background.

I don’t find that compelling at all. I’m not interested in the “great man” theory of history. It’s interesting to notice that relatively few women write about Napoleon, or that relatively few have written his biography. There are a lot of wonderful female scholars and scholars of many diverse backgrounds who are interested in him, but not necessarily interested in the question of how great he was or whether he is the ultimate example of a great and self-made man.

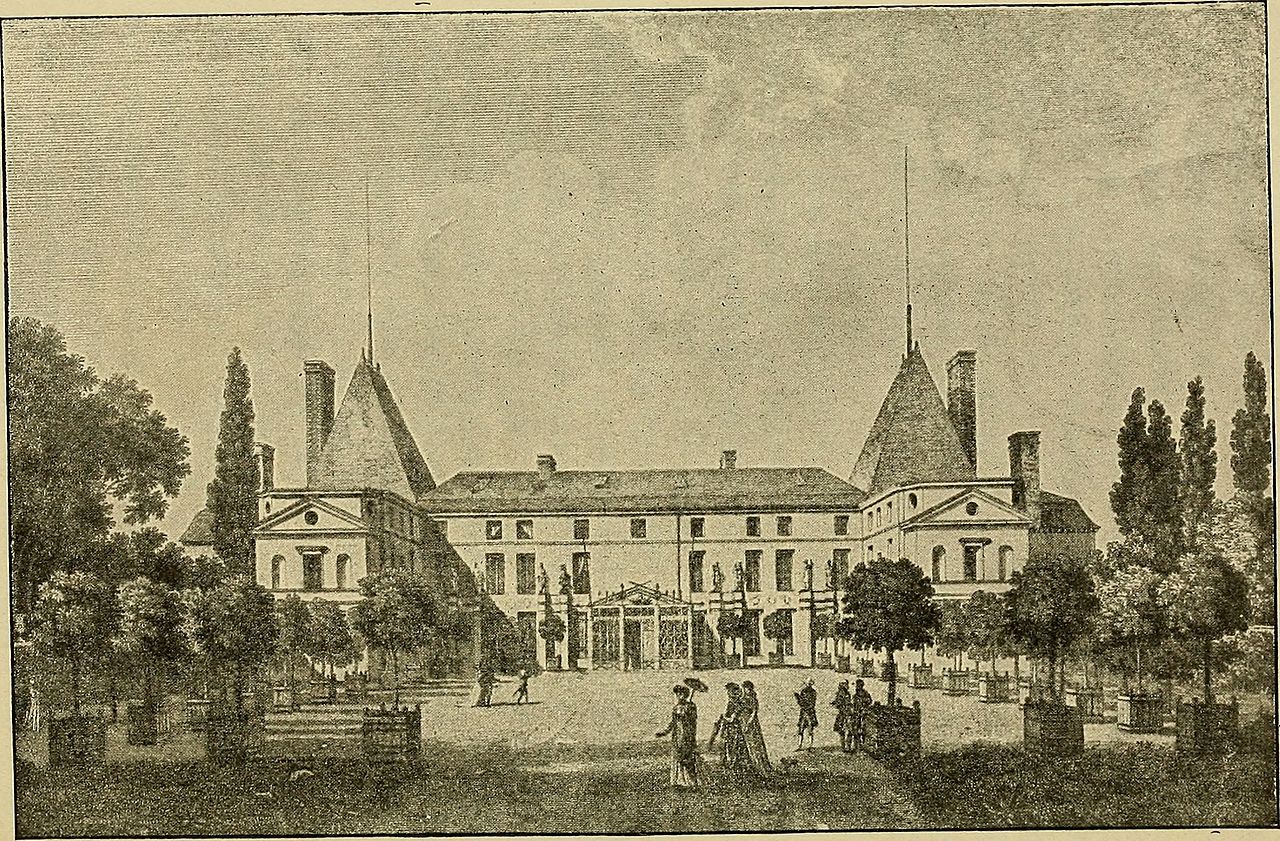

Gardening with Josephine

The garden that Napoleon and his wife, Josephine, created at ‘Malmaison’, their marital home, is a wonderful example of his interactions with the natural world. Napoleon and Josephine clashed over their vision of what their garden should be. Napoleon favoured the French style, which was one of order, of tightly clipped topiary, of straight paths. Josephine wanted a garden in the English style – without formality and with winding paths and romantic vistas. Josephine ended up sectioning off a part of the garden so that Napoleon could have it the way he wanted – more orderly and with neater plantings – and the rest of it, she designed with her English gardener’s vision.

Napoleon Bonaparte’s house, ‘Malmaison’. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Discover more about

Napoleon's life

Scurr, R. (2021). Napoleon: A Life in Gardens and Shadows. Chatto & Windus.