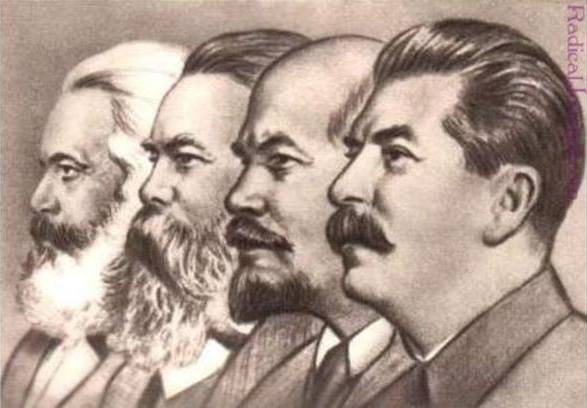

This theory of Marxism goes together with the determinist theory of history. Originally, this was something which came from the Owenites, which is the idea that man is a natural being; he is determined by his environment, he’s governed by the desire to increase pleasure and reduce pain and, therefore, he’s a determined figure. He’s not free, but a product of his environment.

This is challenged in some of Marx’s writings by the idea that man transforms history. But in the period of the Second International, between the 1880s and 1914, this idea is very much subordinated to the idea of historical determinism. And this historical determinism gets attached to Marx all the way through to the end of the 20th century and the fall of communism.