But I think that what psychoanalysis does is not recommend patriarchy. It analyses patriarchy. The truth to it is that women don’t have the same Oedipus complex as men – It’s a very complicated question and too long to describe here. What I was trying to bring to the attention of feminist groups was that what makes for patriarchy is an unequal position, and psychoanalysis analyses it. It’s one of the few ways in which we can analyse women’s unequal position. We must, therefore, use an analysis of patriarchy rather than subscribe to it, so that we see where it’s pointing out that women go into a position from which they act themselves as oppressed as well as get oppressed by men.

Psychoanalysis and the Feminist Revolution

Emeritus Professor of Psychoanalysis and Gender Studies

- Psychoanalysis is absolutely central to the feminist revolution. It doesn’t mean that everybody has to study psychoanalysis. What is essential is that we live how we are as women, as men too, of course. That we live ourselves unconsciously as much as consciously.

- Women live as oppressed people as much as men oppress them. In some sense, we all have to live how we do in an unconscious way as well as in a conscious way, which is why anything to do with psychoanalysis is so important.

- Psychoanalysis can help explain the second sex position of women because women are excluded from the main prohibitions of patriarchy. They are excluded from being prohibited to have incest with the mother. That’s not relevant for them.

Conscious and unconscious thinking

Psychoanalysis is absolutely central to the feminist revolution. It doesn’t mean that everybody has to study psychoanalysis. What is essential is that we live how we are as women, as men too, of course. That we live ourselves unconsciously as much as consciously. Understanding that is the concern of feminism.

So, what do I mean by unconsciously? There are two types of unconscious. We live ourselves unconsciously in a simple way: we just don’t know about things. We forget about things. I would call that, technically, pre-conscious. Then there’s something much more important – and this is the subject of psychoanalysis – which is the dynamic unconscious. It’s a different way of thinking. The easiest way to think about an unconscious way of thinking is to think of dreams. Conscious thinking is like what we are doing now. We are talking rationally, we hope. But, unconsciously, it is as though we were dreaming. That’s incredibly important because we spend an awful lot of our time thinking unconsciously.

If you think about men and women, though I’m obviously interested in women here, women live as oppressed people as much as men oppress them. In some sense, we all have to live how we do in an unconscious way as well as in a conscious way, which is why anything to do with psychoanalysis is so important. Even if one doesn’t want to actually study it, which I don’t think you have to, one has to be aware that it’s there because psychoanalysis is the only method that we have, so far, of understanding unconscious forms of thinking.

Feminists’ opposition of Freud

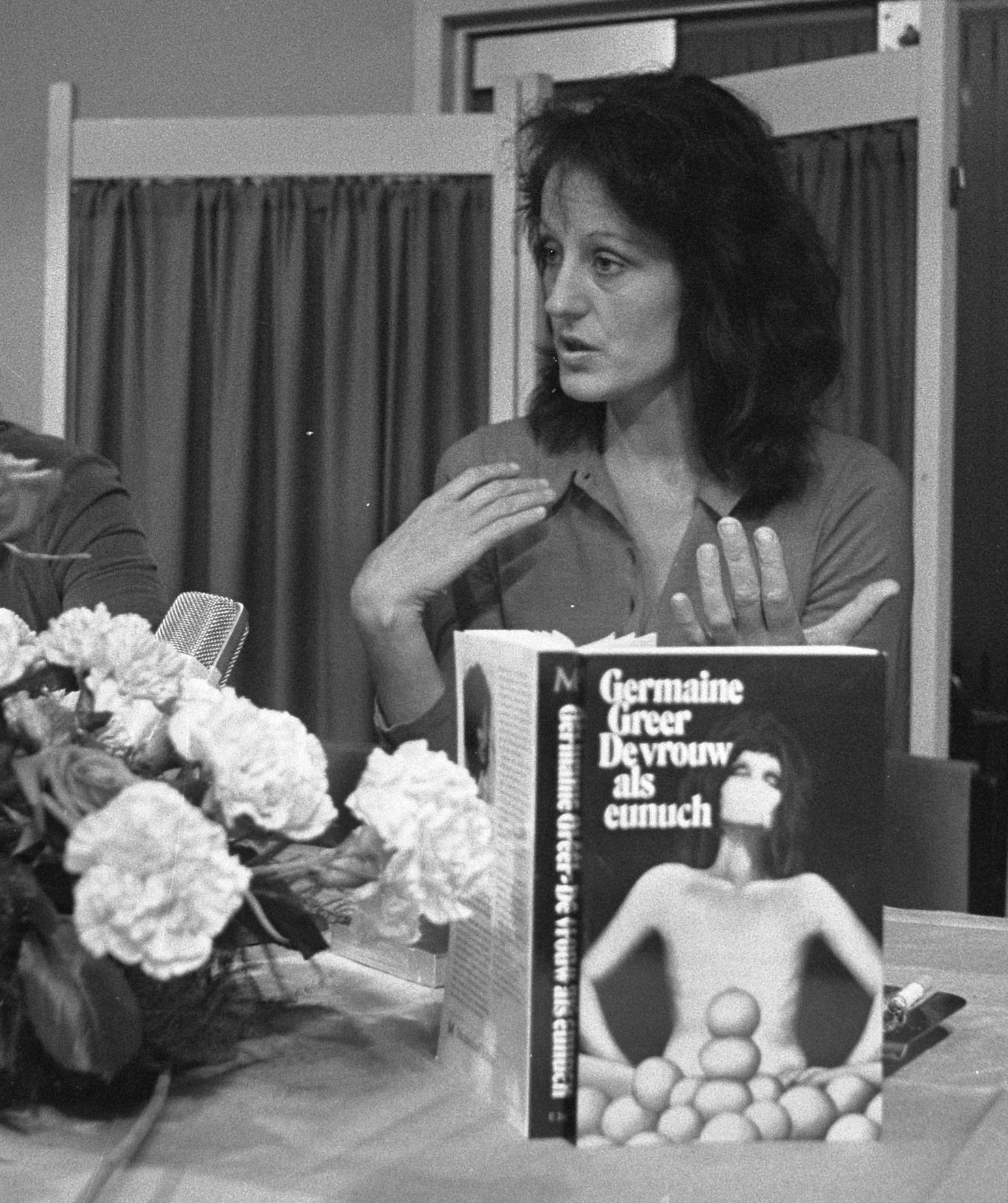

Sigmund Freud was under attack by, particularly, American feminists and people like Germaine Greer in the UK, for the very simple reason that it seemed that psychoanalysis and Freud were creating what Greer called “the female eunuch”. They felt that women were being given therapy in order to be made into good wives and widows and girls and daughters, and not to be equal. There is a truth to that.

Germaine Greer in Amsterdam. 6 June 1972. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Using Freud to study feminism

The way to use Freud as a feminist is quite simple. It is to say, look, we can take over and use this very complex and detailed analysis of patriarchy. We can make it fair. We can make it our own by seeing what it is that it’s describing. In my first work on that, that is what I was doing. I was looking at patriarchy and saying, let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater. Let’s say, here it is: an analysis of patriarchy. We are saying we are suffering from patriarchy, which we are. Let’s use this analysis of patriarchy to further produce a feminist understanding of patriarchy.

A feminist study of patriarchy

The feminist study of patriarchy says that a girl does not have the same Oedipus complex as a boy. The boy’s Oedipus complex is incest with the mother and terror that if he persists in incest with the mother, the father will castrate him. Now, the woman is described as already castrated, and that’s Germaine Greer’s “female eunuch”. But, wait a minute. When we’re not female eunuchs, what are we if we’re already castrated? What does that mean? What does castration mean? What is penis envy? What are these concepts that are used by Freud to define psychoanalysis, and to define what actually happens in patriarchy?

Let’s look at it as a social situation, not one that’s prescribed by biology but as something that all cultures produce. Now, why do all cultures produce this? First of all, every culture in the world regulates some excesses of sexuality. There’s some sexuality that is beyond acceptance within any culture. That has an umbrella title, which is incest. What psychoanalysis does is say that all cultures have incest. Psychoanalysts are far too narrow in their definition of incest, thinking that incest is only how the Western notion defines it. Incest could be to not have intercourse in the bush, for example. Incest has a wide range of excesses of sexuality, but there is no culture that doesn’t prescribe some excess sexuality. Incest is useful as a cover term for the excesses.

All societies have some form of killing which must be prohibited because it is excessive. That form of killing is known as murder. All societies prohibit murder. So, what psychoanalysis does is say, what is it that we’re doing when we prohibit incest and we prohibit murder? That applies only to men.

Change: one step at a time

A colleague and friend, Jacqueline Rose, has just written a book called On Violence and On Violence Against Women. There is so much discussion on this now that suddenly it is being realised that there is a huge amount of violence against women, especially domestic violence. When I first started in this field, when women were being beaten up and assaulted in the home, it was illegal for any neighbour to go in and help the person screaming, or even for the police to go in unless there had been a murder. That was not allowed. Now, it is.

Movement NI UNA MENOS, “Not one [woman] less”. Argentine fourth-wave grassroots feminist movement that campaigns against gender-based violence. Photo by Maria Rocio de la Torre.

There’s a movement. There’s a change. But psychoanalysis can help us say, if that’s what patriarchy does, let’s see if we can get that changed. There are many small changes en route to this understanding of patriarchy. But the major one is that it describes how women and men internalise this prohibition on incest and prohibition on murder differently so that women are ruled outside of it altogether. There’s no prohibition on women. They’re just already outside the framework of patriarchy. They’re just objects of the oppression.

Engaging with patients

Even though I wrote the book Psychoanalysis and Feminism, I didn’t expect to practise as a psychoanalyst. I expected just to understand where Freud got these ideas from. I did, indeed, learn where he got those ideas from, but that didn’t make me a feminist psychoanalyst: it made me a psychoanalyst. Not all feminist psychoanalysts are feminists. I am a feminist and a psychoanalyst.

What I do as a psychoanalyst is listen to what my patients talk about – and don’t know that they want to talk about because it is unconscious. My work is to understand that the patient knows what their problems are but doesn’t know that they know. So, what I’m doing is listening to see if I can help here. My work is to find out what he doesn’t know that he knows; what she doesn’t know that she knows. So, I am a feminist and a psychoanalyst, not a feminist psychoanalyst, but that’s very particular.

Becoming conscious of the unconscious

The question about whether psychoanalysis falls short to address feminist questions is interesting when you think about women as 51% of the population. What we have in common is that we all have an unconscious. So, the unconscious has a huge part to play, some larger part than our conscious. But it doesn’t have a part to play in what feminism might decide is the next best important political thing.

An example of this conscious-unconscious play is that it’s much more important to be aware that it is not that the movies being made were the main object and that the sexual harassment and rape, etc. was a side issue. It was that the movies were a side issue and the central issue was the rape and sexual harassment.

You can use psychoanalysis there to understand things further, if you want – or not use it. So, it’s both. If you want to use it, it speaks to a very big part of our unconscious lives. If we don’t want to use it, it is because it’s not how we’re thinking about women. This is the point at which you enter into the feminist struggle. So, psychoanalysis and unconscious thinking is as useful as you want to make it.

The second sex nature of women

Psychoanalysis can help explain the second sex position of women because women are excluded from the main prohibitions of patriarchy. They are excluded from being prohibited to have incest with the mother. That’s not relevant for them. They’re already like the mother, a female eunuch; that, and they are already, of course, envious of the penis, if that’s what you want to be bothered about, because anybody who is oppressed is envious of the person who’s got something more than them. It’s not a very profound concept. It’s there from oppression.

Stone Age relationship. Photo by Everett Collection.

The feminist parts of ourselves have to, as it were, take a social perspective on what psychoanalysis is teaching us so that if, for example, you’re looking at femininity, you’re looking at the psychoanalytic construction. If you’re a psychoanalyst, you’re looking at the psychoanalytic construction of femininity. Yet, I would, for example, want to look at the social implications of what I’ve learned about femininity, and those would relate to things like the fact that women do all, or most, of the caring, or that it’s a feminine position to do the caring. So, I would bring in the social dimension of my feminist interests. Somebody else might bring in a biological dimension of their feminist interests because there are, obviously, biological factors as well as social ones.

You can use the fact that we are all unconscious a lot of the time to understand why we internalise being oppressed. You can also use it to decide that you won’t internalise it because you choose to combat that with a social understanding of it.

Discover more about

the study of psychoanalysis and the feminist revolution

Mitchell, J. (2000). Psychoanalysis and Feminism: A Radical Reassessment of Freudian Psychoanalysis. Basic Books.

Mitchell, J. (1966). Women: The Longest Revolution. New Left Review, 40, 11–37.

Mitchell, J. (2014). Woman’s Estate. Verso.