While trying to understand these big questions about the nature of logic and how science is equipped to describe the ultimate structure of reality, Wittgenstein also wondered: what are we doing as philosophers? What is this subject matter that is not itself science, but somehow comes before or underpins the scientific inquiry? It’s a question to the nature of truth, the nature of representations of reality, the nature of logic. That makes his project very central to philosophy.

Wittgenstein and the ambition of philosophy, logic and language

Professor and Director of the Institute of Philosophy

- Originally an engineer, Wittgenstein became deeply concerned with logic, language and the nature of philosophy itself.

- In his work Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Wittgenstein tries to understand how language can describe reality, suggesting the foundations for a logically perfect language.

- Having realised that he hadn’t exhausted the problems of philosophy, Wittgenstein begins to write about the nature of explanation. He thinks that sometimes what we need is not another explanation but a better description.

An outsider to philosophy

Ludwig Wittgenstein is often thought of as the philosopher’s philosopher. That’s because as well as giving us philosophical themes to think about, he was deeply concerned with the nature of philosophy itself.

He started as an outsider. He was an engineer who was focusing on aerodynamics. While studying in Manchester, he began to wonder: what is the nature of the mathematics that I’m using in my science? What is mathematics about? What are these propositions that seem so certain? We know without doubt that seven plus five equals twelve. But when we talk about numbers, what are we talking about? Where are numbers? What sort of objects are they, if they’re objects at all? They don’t just depend on the mind; we know they’re somehow something very certain to which we must make our science answer.

Questioning the nature of truth

Wittgenstein started to worry about the nature of mathematics. He discovered that Bertrand Russell, a philosopher in Cambridge, was working on this problem and trying to see if he could address the nature of mathematics as a part of logic. Wittgenstein then became obsessed with this project and wondered: how are we to understand logic? How are we to make sense of logic as both part of our thinking and something that can be located in the language we use for science and mathematics?

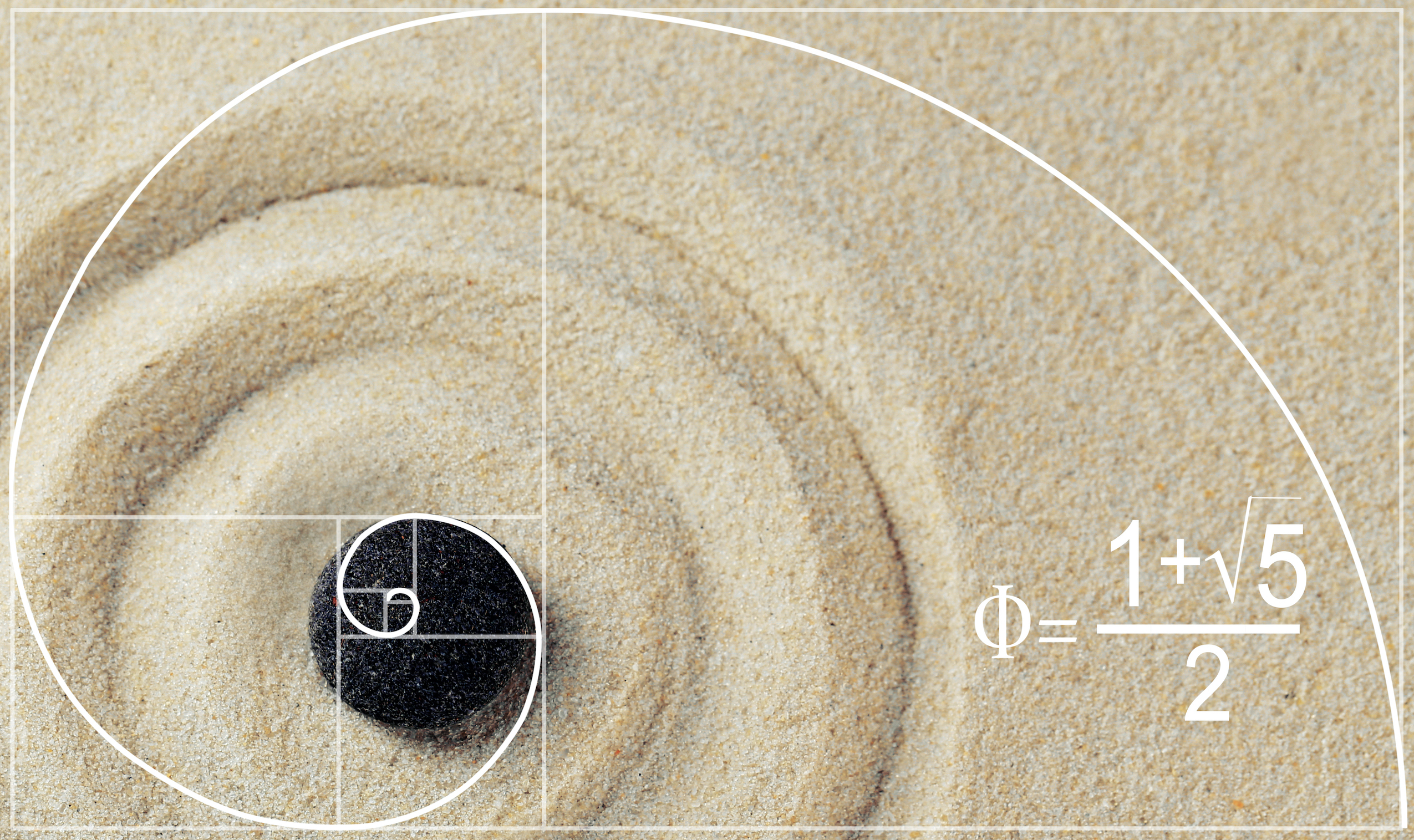

Photo by Africa Studio.

Logic and language

Wittgenstein was aware that we use logic and language to describe states of affairs in the world. In science, we try to come up with theories that are couched in language, and we try to make sure they’re an accurate representation of how things are and the way things work.

At the same time, Wittgenstein makes problematic or puzzling the way in which language can be up to the job of connecting us to reality. With this deep understanding of how hard it is to say how language does this job, he becomes fascinated by an ambitious project to see if he can capture the way in which language can be fit for the job of describing truths and the nature of reality in propositions.

He starts to formulate a very ambitious project, published in his famous work Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, where he tries to see if he can work out: how can language be fit for the job of describing reality? And how can the possible ways language can be configured in the system give us the ultimate boundaries or the ultimate structure of reality? Moreover, could the limits of language actually be the limits of the world, or the boundaries of reality?

A perfect language to describe reality

Wittgenstein imagines that he’s going to provide the foundations for constructing a logically perfect language: a language which is not sloppy and loose and vague, like our ordinary language, but very precise, highly organised and systematic. That will be the language in which we can do science and describe reality.

He doesn’t give us examples of propositions in that language because it’s a language that’s not yet formulated. It’s a language which – if it works – will tell us that each of the names in the sentences or propositions of that language must be a name of an ultimate particle, or simple, in the world. Since we don’t yet know what the simples are, we don’t yet know the names, but he’s providing the foundations for constructing such a system.

As he imagines that this system will describe the way the world is, the totality of facts, he then suggests that rearranging the parts of that language will give us the way to describe all the possible facts – states of affairs that don’t exist but could have existed. Now, he thinks, he’s captured the possibilities of not just language but how reality could be. But where is logic?

Logic is not yet another proposition about things in the world. When we say, ‘no proposition can be true and false at the same time’, that’s not another fact that we’re describing about the world. Instead, it’s a limit to what we can describe. It provides the boundary conditions of how language can function to describe reality. So Wittgenstein thinks that logic isn’t part of the subject matter of a fact-stating language, but it describes the boundaries or the permissible limits to language. That’s how he tries to accommodate logic within his picture of a scientific language.

Solving the problems of philosophy?

Wittgenstein thinks that if he has succeeded in describing all the possibilities of the way the world is in a systematic, formalised language, and the boundaries of that language are the logical possibilities, then he’s done the full job of philosophy to understand how we relate to reality, and how we have a logic that governs our propositions and our thinking. But the one thing he hasn’t been able to do is to talk philosophically about that relationship.

This is why Wittgenstein has something in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus that is both fascinating and elusive. The idea is: what is the relationship between language and reality? That can’t be stated as yet another proposition. You can’t say what that is, but you can show it. This distinction between saying and showing is very important to Wittgenstein. You can indicate where the boundaries are, but you can’t draw them precisely, because when we have the idea of drawing a boundary, we have the idea of standing on both sides of it. How can you draw the boundary without already anticipating what lies on the other side? But since Wittgenstein thinks the boundary is the limit to reality, to intelligibility, you can only show, not state, where those limits are.

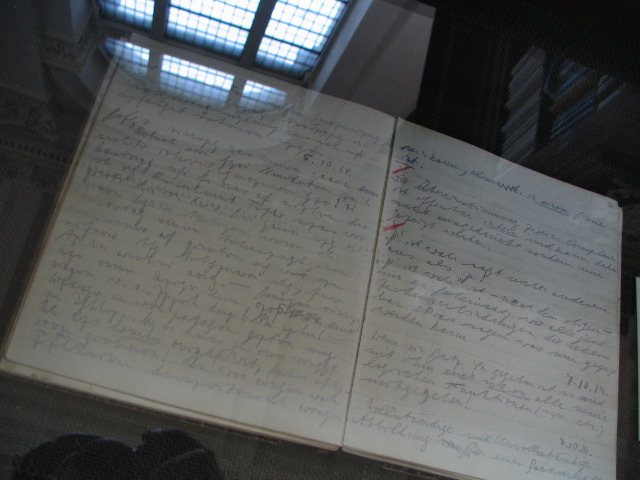

Entries from October 1914 in Ludwig Wittgenstein's diaries (published in English translation as Notebooks 1914-1916. Edited by G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright. Blackwell, Oxford 1961). Photo from private archives, made by a. ziel in 2006, in Wren Library, Cambridge. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

At the end of the Tractatus, he thinks that he’s given the limits of what can be said intelligibly. If philosophers want to ask any more, we have to silence them. ‘Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent’ is the last proposition. Wittgenstein thinks he’s solved the problems of philosophy. He leaves philosophy, he goes back to Austria, and he becomes an amateur architect designing a house for his sister. He was convinced that there was no more to do. But, of course, we know he changed his mind.

Puzzled by the nature of explanation

Very slowly, Wittgenstein comes to realise that he hasn’t exhausted the problems of philosophy. That was almost inevitable; this is somebody who’s a very deep thinker. He’s thinking fundamentally about not just what is the right philosophical picture of language, reality and the limits of thought in general, but what it is that philosophy is trying to do.

He realises there’s still a niche he can’t scratch. There’s still a desire for explanation. Philosophers, even if they have provided what we think of as a total picture of reality and our relationship to it, will still want more explanation; there will still be something they need to understand.

Wittgenstein became intrigued and puzzled by what it was that constituted a philosophical explanation. We know a scientific explanation is often about causality or about mechanism, but when philosophers want an explanation, what will satisfy them? And in this middle period of Wittgenstein’s thinking, he starts to write about the nature of explanation.

A matter of description

Wittgenstein becomes concerned that the problem of philosophy should not be to go on seeking some special mysterious explanation of the underlying nature of language or the underlying structure of the mind. Instead, he wants us to be aware of how things actually are. Instead of an explanation, a digging beneath the surface to find more and more, he wants to remind us that nothing is hidden; that everything is in view; that we don’t necessarily have a correct way of seeing things. What we need is not another explanation, but perhaps just a better description.

Wittgenstein begins to wonder what it is that philosophers are craving when they seek more and more explanation. Here is something that’s given to them: everyday reality, the use of their language. And then they begin to wonder, but how can it be like this? Why do these mere sounds have meaning? Why do marks on paper mean something or stand for something in the world?

He thinks we become puzzled because we’re actually distorting the phenomena that we’re trying to describe. When you realise that the sounds I’m making are immediately meaningful to you, you realise you’re not puzzled. You don’t have this problem of saying, but how do I get from sound to significance? Similarly, he gives up the idea that underneath language there is a logical form or structure, or an essence of language, which we have to seek out and explain in philosophically rigorous terms.

Seeing the surface for what it is

According to Wittgenstein, what lies before us is fully in view. There’s nothing hidden. We should resist the temptation to dig below the surface, but we must see the surface for what it is. Instead of describing the surface of language as mere noises or marks, we have to see that it’s the use of expressions that human beings, minded individuals, make to make themselves intelligible to each other.

Wittgenstein gives up the idea of language as a formal system. He says there’s nothing wrong with ordinary language; it doesn’t need to be reformed and systematised. There is no essence to language. There’s just a set of uses and practices and language games, as he says, that we play with.

Photo by abdelsalam.

Therefore, to give a description of language and to capture it as it really is, instead of to tidy it up in the way philosophers thought it should be formalised, we have to see language as more like a city, with different periods of building, different suburbs, different streets and different parts. When we see that it’s organic and organised in a slightly meandering way, we’ll come to understand what it’s really like, and we won’t strain after a philosophically impossible, rigorous view of what it should be like. His job is to try to stop philosophers looking for something that they can’t have.

Discover more about

Wittgenstein, logic and language

Lepore, E., & Smith, B. C. (Eds.). (2008). The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Language. Oxford University Press.

Smith, B. C. (2010). Meaning, Context, and How Language can Surprise Us. In B. Soria & E. Romero (Eds.), Explicit Communication: Robyn Carston’s Pragmatics (pp. 92–108). Palgrave Macmillan.

Smith, B. C. (1992). Understanding Language. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 92(1), 109–142.