Broadly speaking, these are three very different kinds of State. What runs through all of them was the duality of the State under colonial power – a duality, sadly, which continues to this day.

The fragility of Middle Eastern States

Professor Emeritus of Politics of Middle East and North Africa

- When many Middle Eastern States became independent, they had a dual State in operation: the official institutions of the State and, behind the scenes, a powerful shadow State of networks.

- The model of the republic promises to make power accountable to the people. In countries like Tunisia, where the re-establishment of a republic is a stronger possibility, there’s a struggle to ensure it doesn’t become a vehicle for the privileged.

- Many disputes about borders, identities and class privileges within Middle Eastern States exist because those who occupy positions of privilege have not yet convinced the public that they have a right to be there.

Three very different kinds of Middle Eastern States

States have very varied histories across the Middle East. One needs to think about what kind of effect that’s had on their contemporary politics. You have the States that were effectively long historical entities, such as Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco and Iran. You also have the States that were created out of the Ottoman Empire by the European powers at the end of the First World War, where lines were drawn on the map by the Europeans to decide where the boundary of Syria and Iraq, for instance, should lie. But you also have the other category of States, which are the groups of Arabian Peninsula sheikdoms, tribal sheikdoms, that only became States because of European colonial protection, guidance, definition and recognition.

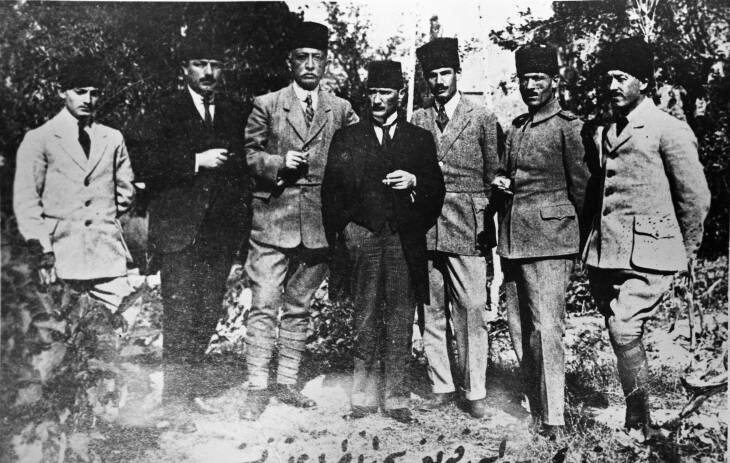

The Turkish National Movement encompasses the political and military activities of the Turkish revolutionaries that resulted in the creation and shaping of the modern Republic of Turkey, as a consequence of the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Emergence of the dual State

The European States were very keen on developing a powerful administrative apparatus. They gave great definition to territorial boundaries, administrative apparatuses from the centre, and so on. In many senses, they were trying to institute what a modern administrative State should be. But they were also undertaking another project to make it work in their favour, which was to develop what one might think of as the colonial model of the State. That is to say, operating behind the scenes – through local elites, local powerful traditional leaders, so-called traditions often built up by the Europeans themselves – to create a different web of power behind the official institutions.

When many of these States came to independence, they had a dual State in operation. There was an official State with the ministries, the public bodies of the State itself, the institutions of the State. But behind it, there was often an increasingly powerful kind of State, which is the shadow State – networks of association, corruption, patrimonialism, sometimes kinship and sometimes ideological fellowship. The shadow State was a way in which power was mediated and never went through the public institutions of the State, and was certainly not accountable to the citizens of that State.

Cultivating the shadow State

By the shadow State, one means the sometimes-unacknowledged links that mediate and effectively ensure power runs along certain lines. No State is immune to that, neither in Western Europe nor anywhere else. We have our unspoken and informal forms of association. What’s more distinctive in many countries in the Middle East is that these were deliberately cultivated.

For instance, in Iraq, one might argue that all the institutions of the State were enacted. The Parliament, the military and the ministries were centred in Baghdad, and civil servants were trained in them. But those who held power were often the unacknowledged members of the elite, who were there because either they were wealthy in the old regime, or because in the new regimes they were military officers or allied to the clans of those who had seized power. So particularly in Iraq, but elsewhere as well, one saw shadow States emerging: people who were dependent upon, in the Iraqi case, Saddam Hussein and the clans around him for their preferment and their power.

Equally, you saw that in Syria, with the Assad clan dominating all aspects of power, the economy and the security apparatus. It becomes a self-reinforcing aspect of the fact that you only promote people you trust. Often those are people who come from your same background: your rural background, your kinship background, possibly even your sectarian background. That becomes a skeleton, a framework for the shadow State to operate: a State of associations, of forms of nepotism, but also forms of violence to ensure that others are kept out.

The republic as an alternative model

One of the advantages of the republic, and one of the reasons why the idea of the republic has been so powerful throughout history, is that it seems to hold the promise of making power accountable to the people. It is a citizens’ State, a State that belongs to the citizens. But the reality in many of the republics that emerged in the Middle East and North Africa was rather different. Instead of being responsible to the citizens, the citizens had to answer to those in charge of the republic itself.

With the uprisings of 2010–11, many in the region thought this was a possibility of re-establishing what true republicanism was. It was a chance to seize back the idea of the republic – which had been used as a justification for authoritarian regimes – and to deliver it to the hands of the people. In fact, many people called the huge demonstrations from January to February 2011 in Tahrir Square, in Cairo, “the Republic of Tahrir” because people were acting out what it meant to be citizens of a republic. They were taking care of each other, acting equally with no one oppressing anyone else. Hierarchies evaporate. Of course, it was a moment in time, a moment in history.

Egyptian revolution – Crowds carrying Egyptian flags in Tahrir Square. Photo by Tarek Ezzat.

In Tunisia, where the possibility of re-establishing the republic is more salient, serious thought has been given to the question, how do you ensure that the republic doesn’t just become the vehicle for the already powerful in society? That’s one of the struggles that the Tunisians are facing at the moment. There is a battle for the soul of the republic, which is not, as was originally thought, between a secular and an Islamic idea of a republic, but rather between a republic of the privileged and powerful, and a republic of the people.

Divisions in Iraq since 2003

After 2003, there was a concentrated effort by external powers and exiled Iraqis to reconstruct the Iraqi State as they thought it should have been. The result they came up with was the communalisation of the State: the allocation to different groups, generally designated by their sectarian identity but also by their ethnic identity, of different positions within the State itself, as well as down through the administration of the State. It was a system of special privileges given to those who belong to particular communities.

Many Iraqis were appalled because they saw in this a destruction and a rupturing of any sense of Iraqi national identity. They were also wary of the kinds of people who had come to the fore as a result of this communal division of the spoils in Iraq itself. Nevertheless, that system is built into the Constitution. It’s built into the structures of the State. And it’s exactly against this that people have been demonstrating, very vociferously, since 2015, asking that it should disappear.

The model, in some senses, was that of what the Americans thought Lebanon was, without perhaps realising that Lebanon underwent horrendous civil wars on the basis of this so-called communal division of the spoils. So there’s a sense in which the model was misplaced. It’s had some appalling effects because of the civil war that raged through Iraq in 2006, 2007 and 2008, and also because it created a regime of massive corruption, in which corruption is clarified or justified by the reference to your communal identity.

Violence and State authority

Some have argued that sovereignty itself is defined by the right to take life and the right to give life. Any sovereign State is a State that can inflict death or call upon people to die, just as it can give life as well. That’s one of the reasons why in political history, not just in the Middle East but also elsewhere, people have become wary of those they give that right to. Who exercises that right to life and right to death in the name of the State, and by what right do they do that?

Since the State can do these terrible things, people in the Middle East, just as elsewhere, are asking: what say do I have in not simply whether the State should do something, but how it should do it, and who’s exercising it in the State’s name?

One could argue that the uprisings of 2010–11, just as previous ones, have been to question the right of those in power to exercise power in that way. Is it arbitrary? Is it done through due process of law? Is it accountable to the people? Unfortunately, the answer is no in most cases, leading people to become enraged and to exemplify their desire to hold their State accountable.

Spraying Khaled Said's stencil on the Ministry of Interior Gates. 6 June 2011. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

It’s not a total coincidence that when a young man called Khaled Said was brutally killed in public by the police in Alexandria at the end of 2010, he became a symbol for all Egyptians about the violence of the State. “We are all Khaled Said” became the great cry. The notion that the State could take his life away and not be held accountable for it was part of it.

The fragility of the State

One interesting aspect in the Middle East is the way in which the State does or doesn’t coincide with what you might call the political field, or the place where people think real politics happens. The whole dispute about borders, identities and class privileges within Middle Eastern States has to some extent been due to the fact that those who occupy positions of privilege have not yet convinced those who inhabit those States that they have a right to be there.

The constant challenge presented to those who rule those States is that the political field, or what really counts in politics – whether it be Islamic values, class values, regional values or human rights – has not been fully addressed by the State itself. It’s the poverty of the State seen through one dimension only – as a repressive apparatus – that really speaks of its fragility, since in many senses it fails to root itself in many of those who come up against it in some quite disturbing and violent ways.

Discover more about

the history and politics of Middle Eastern States

Owen, R. (2004). State, Power and Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Tripp, C. (2007). A History of Iraq (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Kamrava, M. (2013). The Modern Middle East: a political history since the First World War. University of California Press.