At the same time, what you can see if you study emotional behavior and ideas about emotion across time is that they have changed – and sometimes quite dramatically. By that I mean that the gestures, the values, the ideas and the explanations that we have about emotions change; the languages of emotions change.

A brief history of emotions

Historian of Emotions

- Emotions are not fixed; how we express and understand them changes across time and cultures.

- Some emotions, like boredom or nostalgia, were named and defined in specific historical moments.

- Societies have unspoken rules about which emotions are acceptable and when.

- Some of the emotions that are going to become more spoken about are emotions to do with our response to the climate crisis.

Defining emotion

Among philosophers, neuroscientists, psychologists and historians like me, no one really agrees with what an emotion is. There is not a simple definition of an emotion. I find it very useful to make a distinction between thinking about feeling and emotion. I might say feeling is a more inchoate set of sensations that are happening in the body – pre-linguistic, very fleeting, all happening together. When something becomes an emotion in my mind is the moment when we have given it a name or tried to identify it in some way.

© Pexels

© Pexels

Emotions have a history

It is sometimes counterintuitive to think that emotions might have a history, because surely everyone across the world and everyone across time has always felt fear, anger, sorrow and joy in the same way. I think that is true. In fact, I think it is very important that we do recognize that what we have in common, what humanity has in common, are these shared emotions.

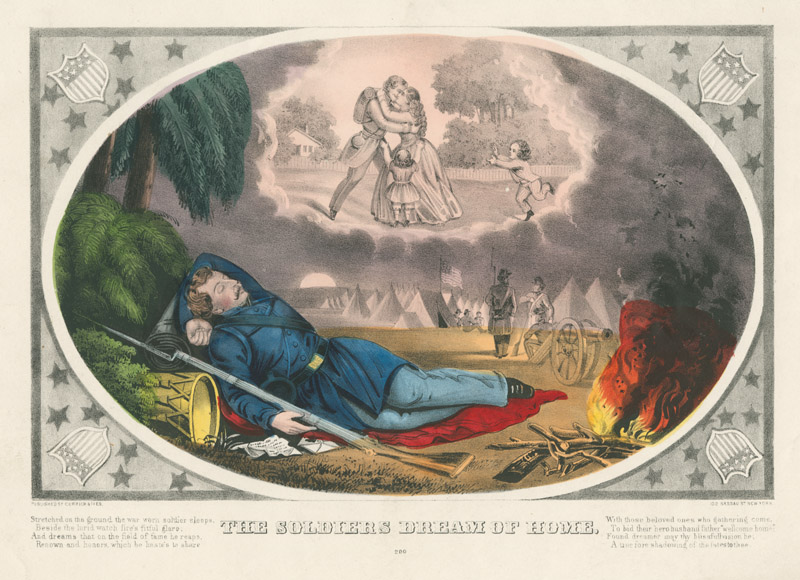

Nostalgia

In the 17th century, doctors diagnosed a new kind of emotional sickness, which they called nostalgia. This was a very lethal form of homesickness. It produced all kinds of effects, from listlessness and lethargy to the eruption of strange boils and the inability to eat. Eventually, in really serious cases, people would fall into a terrible stupor, and then they would die. Nostalgia was a fatal form of homesickness.

© Library Company of Philadelphia via Wikimedia.

© Library Company of Philadelphia via Wikimedia.

In the 19th century, homesickness began to be downgraded as an emotion. It seemed to be rather childish that people could not be away from home for such a long time, and as people began to travel more, as the tourist industry began to boom, as trains began to expand, so the idea of being attached to one particular place began to seem a rather problematic emotion.

That is a curious example of how the values around an emotion might have changed, and so nowadays, you would be unlikely to go to the doctor and be diagnosed with homesickness. Although you might well feel homesickness, it might be an emotion that might be hard to talk about openly or to feel has the status of some other emotions, such as depression or anxiety.

The invention of boredom

As historians of emotion, one of the things we look at is language: how much it changes around emotions, when a particular word comes into circulation and what that can tell us about the particular preoccupations and concerns of a society at any given moment.

Boredom is one of those emotions that, for the Victorians, turns out to have been very significant. The word boredom first appears in, we think, 1853, in Dickens' novel "Bleak House". Of course, people had felt bored before then; people had been irked, or world weary, exhausted by life, fed up and so on. However, the idea that Dickens produced is a noun to describe this particular state, boredom, and he says this is the chronic malady of modern life and a particular issue for Victorians.

© Reading by Georges Croegaert, Musée Carnavalet via Wikimedia

© Reading by Georges Croegaert, Musée Carnavalet via Wikimedia

Now, why was boredom such an issue for Victorians? One of the reasons might have been that with the change in working patterns, by the 19th century, we had the creation of a new moment in the day. This was leisure time. This had not really existed in quite the same way before. Leisure time was the time that you would spend after work and before going to sleep.

Victorians really felt that that leisure time ought to be used very productively for self-improvement and for learning. Victorian society was full of opportunities to go to lectures, museums, the theater, circuses and so on. If you were bored in this kind of environment, if you could find nothing that interested you to do, then this began to seem like an all-purpose sign of inadequacy of some kind.

Boredom also became a topic of very fierce social discussion. It was debated in parliament. Doctors wrote articles about the risks of boredom. Boredom was associated with life in the slums. It was associated with alcoholism. It was associated with the women's movement in terms of imagining a life where middle class and upper class women were more engaged rather than bored. Boredom became a very important emotion.

© Pexels

© Pexels

I think that still lives with us today in our own anxieties about whether boredom is something to be avoided at all cost, whether it is a moral failure or whether, as we are seeing recently, perhaps we ought to learn to embrace our boredom a little bit, in an age where we are so easily absorbed by our smartphones, rolling news and so on.

Emotionologies

Historians of emotions talk about emotionologies. That is the system of rules that govern what emotions can be shown, which ones must be hidden and which ones are appropriate in any given setting. One of the things that we study is the ways in which these emotionologies change across time or change in different communities, even at the same time. When we look at Renaissance textbooks and self-help books, for instance, we can also see that sadness was sometimes an emotion that was actively encouraged.

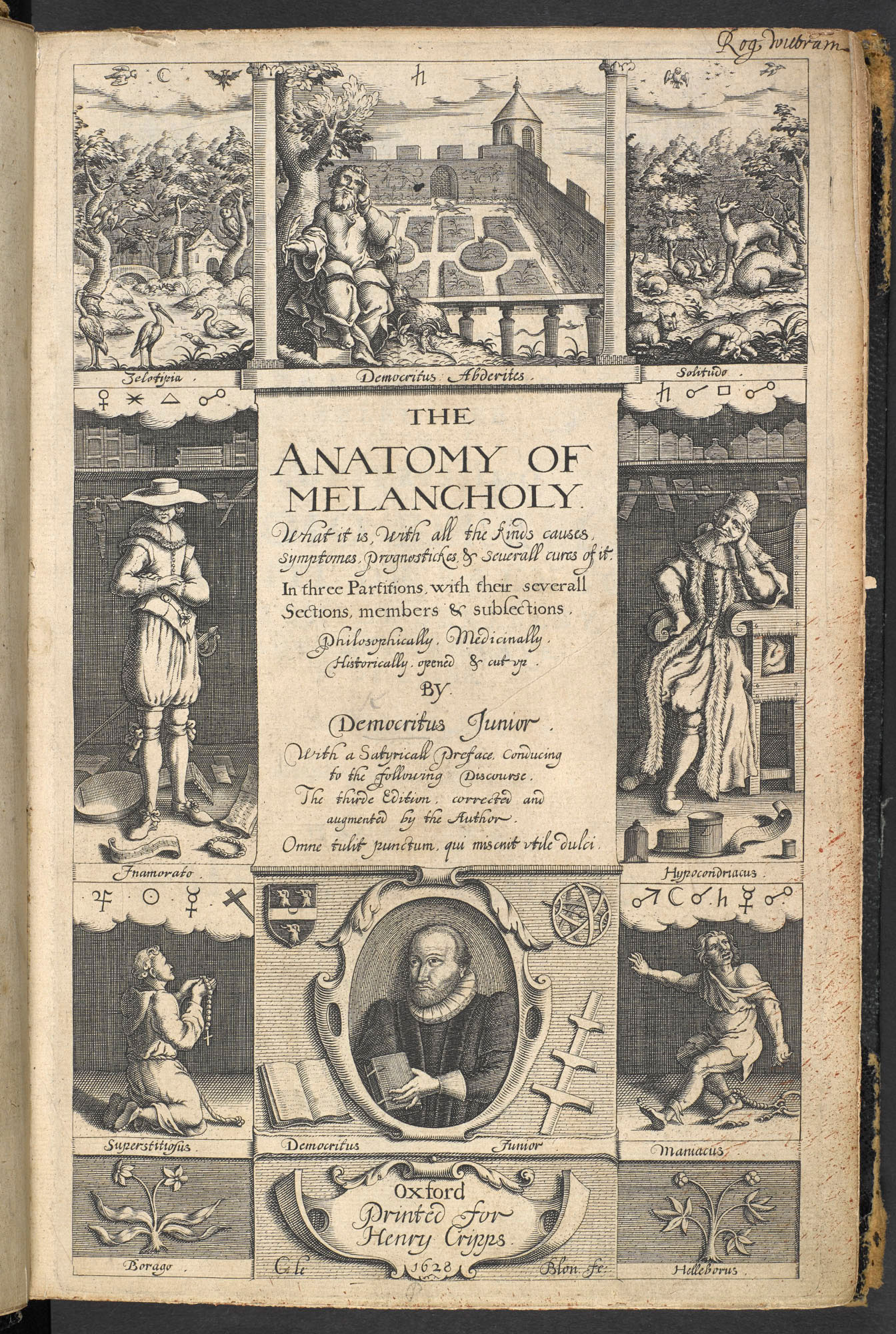

Robert Burton in "The Anatomy of Melancholy" began with an epigraph that says, “When you are sad, be hopeful. But when you are happy, beware.” There is this slight suspicion towards happiness – an idea possibly that what goes up must come down.

© Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy, British Library via Wikimedia.

I think that happiness was associated with being rather unreliable, fleet-footed. At the time, the humoral medicine suggested that the melancholy humor, which was a dark, thick liquid, seemed to weigh the body down, brought it closer to Earth and made people more humble and more God-fearing. Whereas happy people seemed to be flighty, irresponsible and all over the place.

That is quite intriguing, because now, of course, we really value happiness. Happiness is the emotion we should all be seeking, and certainly parents should be happy; bosses should be happy; and people in charge should be happy. We are also rather anxious about sorrow and seek to avoid it, or get over it quickly or medicate in some way. I think that situation might have been somewhat unfamiliar to people a few hundred years ago.

Glimmer of a smile

In 1787, the painter Madame Lebrun, a close personal friend of Marie Antoinette, exhibited a self-portrait that caused a huge uproar. In that self-portrait, you can see the tiniest glimmer of her teeth. This portrait caused a lot of anger and outrage. For centuries, aristocrats had been depicted with their mouths enigmatically clamped shut.

© Self-portrait by Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, The Kimbell Art Museum via Wikimedia

© Self-portrait by Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, The Kimbell Art Museum via Wikimedia

When Madame Le Brun represented herself with a slight smile on her face where you could see her teeth, it was a real break with tradition. It was really reflecting a larger shift that was happening among philosophers at that time, with the enlightenment towards a new emotional regime that encouraged people to be more optimistic, that encouraged an egalitarian, relaxed approach to the world.

Misfortune of others

In our very divided world, we hear a lot about anger and hatred and how this is fueling the political environment we live in now. An emotion I have been particularly intrigued by is schadenfreude. This is a German word from schaden, damage, and freude, meaning joy. This is the pleasure that we might take in the misfortunes of others.

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

One of the reasons why schadenfreude is so important in our contemporary political climate is that it plays an essential role in forming groups, in bonding in-groups and out-groups.

We might feel schadenfreude for all kinds of reasons, because we are envious or because we want to have an ersatz feeling of superiority. We might feel it because of tall poppy syndrome; we do not like people who might think that they are better than us and go off doing more ambitious things, and we might enjoy seeing them cut down to size.

Those are some of the reasons why we might feel schadenfreude; however, the most interesting reasons are to do with justice and with this sense of group identity. Just the idea that we enjoy seeing someone brought to justice is very deep within human culture and human nature.

Culturally unique emotions

When we come across a culture which has diagnosed a particular emotion and bothered to name it, and perhaps in naming it has spoken about it, thought about it, perhaps told stories about it and so on, then we can understand that that emotion holds particular significance for those people at that particular time. When we look across the world, what we can see is a whole range of emotional languages that do not easily translate and that remind us about the extraordinary emotional diversity across the world – but also give us very intriguing insights into particular cultures.

There is an Indonesian word malu, which describes a very flustered, constricted, embarrassed feeling that you might get when you meet someone you really admire. This could be a celebrity, but it could also be someone that you hold in some kind of esteem. It could be a boss or even an elder in your community.

© Shutterstock

I think this is a very recognizable feeling. I certainly recognize that feeling of getting tongue-tied and flustered, saying stupid things and then feeling embarrassed afterwards, "Why did I say that to that person?" I think we have all been there. What I find really fascinating about the fact that Indonesians give a word to this particular feeling is that it seems to matter more in their culture that this feeling exists, that it is worth paying attention to and perhaps is of some value and significance.

In fact, some people argue that the reason why malu has been named in Indonesian culture is that it is very important to have these moments of embarrassment and constriction around their superiors, because it helps to reinforce a sense of hierarchy and a sense of honor between different generations and different hierarchies. I am conscious that we do not really have an equivalent word for that in English. We might say “star struck,” but that is not quite right if you are talking about your boss, for example. We might say “embarrassed” or “flustered,” but those are rather broad words, perhaps because we do not like to imagine that we experience this kind of emotion. Perhaps we want to avert our gaze from it.

Future of emotions

It is true that historians look back because they are interested in the past, but really history is a discipline that is very concerned with the idea of the future. What history teaches us is the ways in which things change and the causes for those changes. It allows us to imagine a future which is different from the world that we are living in now. It allows us to imagine the reasons why our world might change.

I think that some of the emotions that are going to become more spoken about are emotions to do with our response to the climate crisis. We are starting to see some of these words already appearing.

The Swedish word flygskam, which means the shame of flying, is a really intriguing slice or insight into the sense of embarrassment and awkwardness around our behavior in the middle of a climate crisis.

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

The word solastalgia, which was coined by an Australian philosopher, Glenn Albrecht, describes a sense of homesickness for a landscape or place that has been lost due to environmental change. How do we articulate the particular kinds of sorrow, loss and homesickness that a changing world will create? I think those emotions will become very interesting for us in the coming decades.

Hope is not the same as blind optimism. Hope is an emotion we have when we are not entirely certain what the future will bring – but in that space, it gives us the opportunity to act.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

History of emotions

Watt Smith, T. (2016). The book of human emotions: An encyclopedia of feeling from anger to wanderlust. Wellcome Collection.

Watt Smith, T. (2019). Schadenfreude: Why We Feel Better When Bad Things Happen to Other People. Wellcome Collection Profile Books.

Watt Smith, T. (2025). Bad friend: How Women Revolutionized Modern Friendship. Faber.

Watt Smith, T. (2014). On Flinching: Theatricality and Scientific Looking from Darwin to Shell Shock. Oxford University Press.

Watt Smith, T. (2013). Cardboard, conjuring and 'a very curious experiment'. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 38(4), 306–320.