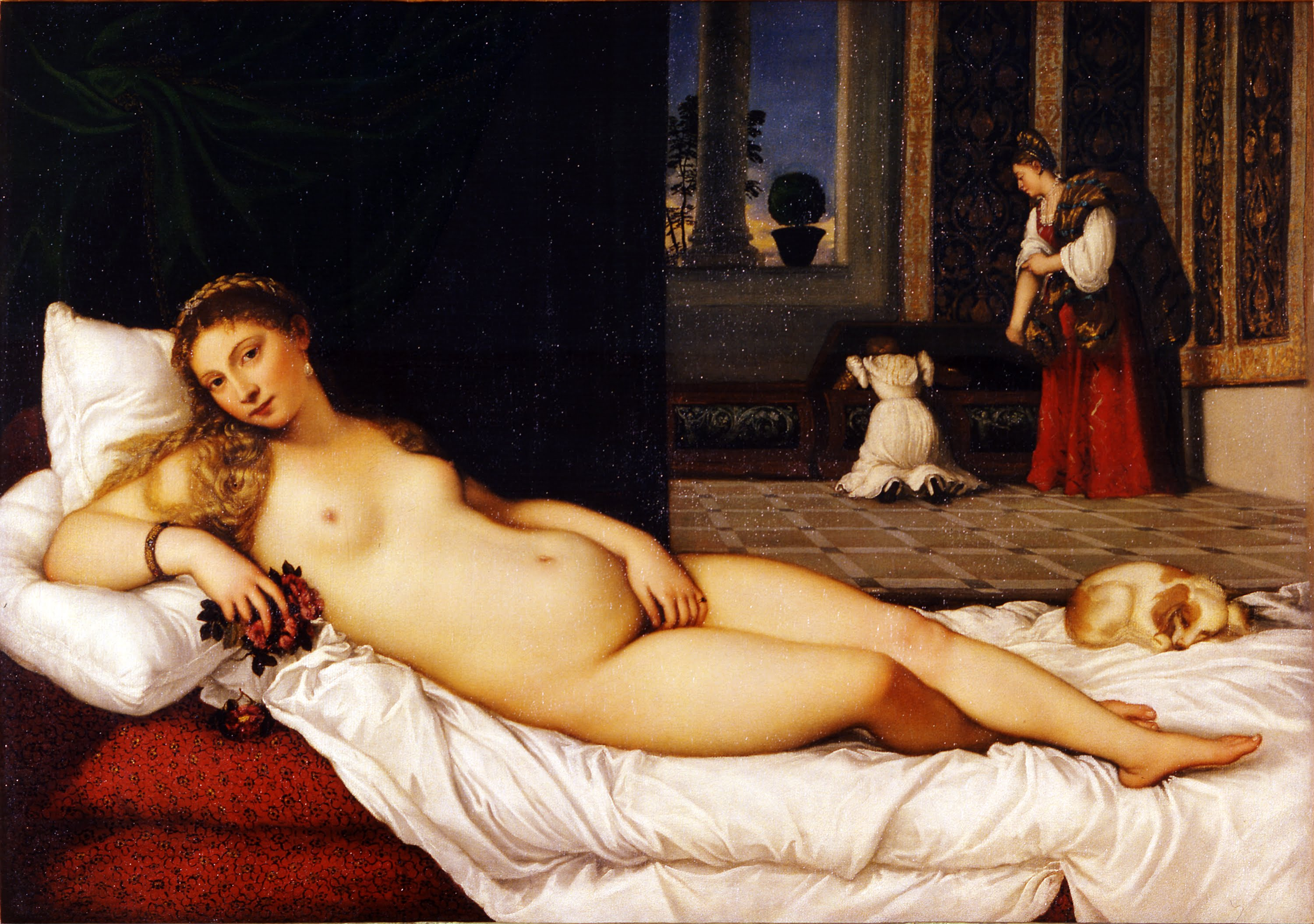

Titian's Venus of Urbino is a case in point. It is probably one of the most famous paintings of a female nude from the Renaissance period, and it displays quite clearly all the desired aspects of a beautiful Renaissance woman. We have a naked woman reclining on her couch with her plump body and these qualities of softness and a passivity that is desired among women in this period. Also, if you look closely at her face and hair, she has long, dark blonde, honey blonde wavy hair. She has arched dark eyebrows.

How the Renaissance shaped beauty

Cultural and Art Historian

- Renaissance beauty ideals, especially for women, were strict and emphasized features like pale skin, soft bodies and delicate facial features, as seen in artwork like Titian’s Venus of Urbino.

- Cosmetic manuals made beauty ideals accessible to ordinary women, offering recipes to help them mimic the looks portrayed in idealized art and literature.

- Men also participated in beauty culture, though more discreetly, with attention to fitness, grooming and youthfulness, despite being criticized for femininity.

- The association of whiteness with beauty excluded many, particularly people of color and working-class women, and black figures were often used in art to visually enhance the whiteness of elite women.

Renaissance beauty ideals

In the Renaissance, particularly for women, but also to a lesser extent for men, there are very precise and unforgiving beauty ideals — and these are promulgated in many different areas.

Venus of Urbino © Titian, Uffizi Gallery via Wikimedia

Venus of Urbino © Titian, Uffizi Gallery via Wikimedia

She has dark eyes. She has rosebud lips; she has the clearest, most beautiful pinky white skin, all of which were qualities that were desired for women in this period — qualities that cosmetics handbooks and beauty recipes told women how to achieve.

It might seem that that is very distant from women's lives, but, in fact, it's part of a much broader culture of fascination with women's appearance and beauty that becomes really noticeable from the early years of the 16th century.

Cosmetics manuals and everyday beauty

Titian's Venus of Urbino and other images like it were very common in this period. You see a lot of images of Venus. Titian is particularly influential in creating a genre of female nudes.

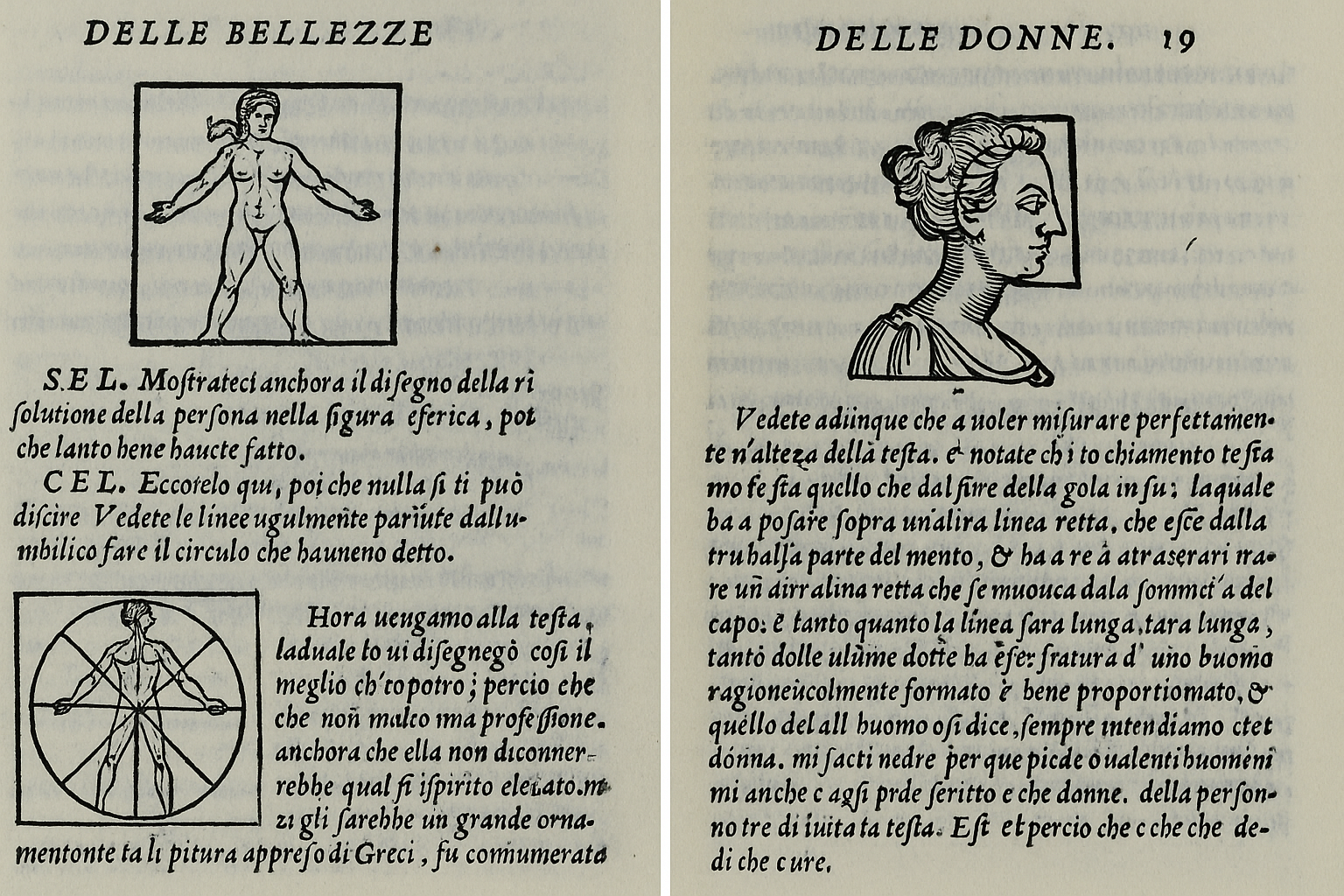

Just a few years — about a decade — before Titian's painting, you see the first cosmetics recipe books appearing. These are not aimed at wealthy women. These are short pamphlets that would have been readily available for a few pennies from a market square in Florence or Venice, and they explicitly tell women how to become Venus-like. They are advertised by being called (one of the first ones is called) Venusta, or Venus-like, and it has an opening rhyme that tells women to come in. It says, this book will be like having a beautiful friend by your side, advising you how to get lovely blonde locks, how to get white skin, how to get rosebud lips, how to get arched eyebrows and so on.

Dialogo delle bellezze delle donne © Firenzuola, Agnolo, Getty Research Institute via Archive.org

Dialogo delle bellezze delle donne © Firenzuola, Agnolo, Getty Research Institute via Archive.org

You have these paintings which seem unrealistic or seem too ideal to mean very much to just a regular person. Then these cosmetic books provide this link between this highfalutin visual culture and actually what a lot of women were doing in their lives and how women felt that they should look.

As you go through the 16th century, these cosmetic manuals proliferate both in manuscript form and in printed form and become much more complex until in 1562; you get the first edition of a book called "The Ornaments of Ladies" by Giovanni Marinello, and this makes the connection explicit. He says the ideal beauty, the beauty that women should aim for, is the beauty shown by the poets and painters. He gives quotes from people like Petrarch, the Italian 14th-century poet, and the 16th-century poet Ariosto, where they describe in minute detail the beauty of their fictional characters. He says this is what you should be aiming for. You can see, even in the 16th century, that women are asked to mimic ideals that are not attainable; they are always being asked to look like fictional characters or like these reclining goddesses on painted canvases.

Male grooming and ideals in the Renaissance

It is very important to understand that beauty cultures affect men as well as women. Even though women are more vulnerable in terms of their appearance, in terms of making a good marriage, for example, men are also very aware of what they look like in this period. There are many recipes and suggestions for men to do things like hide baldness or prevent baldness, for example, to keep looking youthful. There is also an emphasis on the shape of men's bodies. Men are enjoined to do particular exercises to build their bodies; they are expected to keep slender even as they age.

The first printed book of dieting is from the 1480s and is aimed at men who are aging, largely due to a real fashion in this period for very tight hose, for leg coverings, which are very tight.

We also know that some men packed their hose with cotton wool in order to give their legs a better shape. It is important to understand that although in this period men who cared about their appearance were castigated for being effeminate — for somehow that is not a manly thing to do — men also partake in this culture of appearance but do things in a much more hidden way than women. There is pressure on having a beautiful beard, for example, a beautiful way of standing, and this is a constant right through the 16th century that also affects men.

Portrait of a Bearded Man in Black © Giovanni Battista Moroni, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum via Wikimedia

Portrait of a Bearded Man in Black © Giovanni Battista Moroni, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum via Wikimedia

New cultural emphasis on women’s appearance

In the 16th century, there are several factors that bring a new concentration on female beauty. First of all, there is a shift in visual culture, in things like the ability to portray women accurately. This is part of a much wider change in Renaissance culture that you see in Renaissance art. People start depicting the body and the face in accurate ways, and so portraiture, for example, becomes more important.

There is also a new emphasis on finding out the nature of women. There is a whole movement that is often called by its French name, the Querelle des Femmes, which is about women's worth and the nature of women. This debate goes right through the 15th and 16th centuries. It becomes particularly intense in Italy in the 16th century, and beauty – female beauty being superior to men's – becomes a part of that discourse. The whole discussion of beauty becomes tied in with this Renaissance version of feminism.

Mary Queen of Scots © Blairs Museum via Wikimedia

Mary Queen of Scots © Blairs Museum via Wikimedia

The other thing that happens is that you get these very notable aristocratic women who are either widowed or who are acting as regents and are actually quite powerful. I am talking about people like Isabella d’Este or Elizabeth I, or Mary, Queen of Scots — these women who are in positions of power and who do very much care about their appearance. You get a new understanding of the importance of women's appearance and their relationship to a wider set of understandings of beauty culture.

Sprezzatura: the ideal of effortless beauty

Baldassare di Castiglione, in this very important book "The Courtier", which was read all over Europe at this time, coins this idea of sprezzatura as being a very important quality for a courtier — a female and male courtier — to have. Sprezzatura is the idea of effortless grace, effortless accomplishment. This comes through too in ideas of beauty.

Although you might have a book like "The Ornaments of Ladies" that has 4,000 or so recipes in it, the idea is that you should not look like you have made any effort to look beautiful, but you should use these recipes to enhance your natural beauty. The idea that in the Renaissance makeup consisted of these heavy white masks is just simply not the case.

Miniature Self Portrait © Sofonisba Anguissola, Museum of Fine Arts Boston via Wikimedia Commons

Miniature Self Portrait © Sofonisba Anguissola, Museum of Fine Arts Boston via Wikimedia Commons

Natural beauty was a very important part of Renaissance beauty culture, even if that natural look took quite a long time to achieve. This brings it in line with the notion of sprezzatura — that it could take you ages to look nonchalant when you are perhaps fighting with a rapier or doing a dance. It could take a long time, but that effort should not be clear. It is the same with beauty. You should not look like you made any effort to be beautiful. You should just appear like you were beautiful from when you got up in the morning.

Beauty ideals and exclusion

Beauty ideals in Renaissance culture, as arguably today, were really difficult to attain. This difficulty is a leitmotif of beauty cultures. One of the things that was really prized, for example, was pale skin — pale, soft, clear, gleaming skin.

Portrait of Beatrix Pacheco © Jean Clouet, Städel Museum via Wikimedia

Portrait of Beatrix Pacheco © Jean Clouet, Städel Museum via Wikimedia

These qualities that were emphasized as being truly beautiful really excluded a large portion of the population. This includes the new servant class that may have had dark skin, and people who were forced to come into Europe with colonization and new trade with sub-Saharan Africa. There was a real fashion for sub-Saharan African slaves in Italy in the early 16th century — at the same time as certain beauty cultures come about. These people are automatically excluded because of the emphasis on white skin. It is not because these people did not exist; it is quite a deliberate exclusion.

In terms of gender, you also had to look right somehow. You had to be the right kind of woman in order to meet these ideals: this rather passive idea, with soft skin, a fleshy body — not a muscled body, for example. Beauty ideals in this period did tend to be quite strict and quite exclusionary.

Using Blackness to frame white beauty

There is a painting by Titian of a woman called Laura Dianti with a black servant or perhaps a slave. It is really difficult because we do not exactly know the identity of the other person. It is a double portrait, and the interesting thing about this portrait — it is very beautiful — is that it shows Laura in a blue dress with a yellow veil and the child next to her in a multicolored shirt. The contrast between them is really highlighted by Titian. The contrast of Laura's very white skin, her white face and her white hand, is particularly shown against the dark skin of the child's face.

Portrait of Laura de' Dianti with a black page © Titian, Heinz Kisters Collection via Wikimedia

Portrait of Laura de' Dianti with a black page © Titian, Heinz Kisters Collection via Wikimedia

This work brought in a raft of imitations over the next hundred years, where black servants and slaves are shown with white women to highlight their beauty. The reason why we think that was the case in this portrait is because of a documented case where Isabella d’Este asks her agent in Venice to find her a little black slave girl — as black as he can possibly find — so that she can start a collection. It is a very disturbing way of thinking about people, but it was a way of thinking that became increasingly common.

It is linked to the advent of slavery — plantation slavery — which was just at its beginnings, particularly in islands like Madeira where sugar was grown. This was a system started by Genoese merchants, so there is this direct Italian connection, and more and more slaves were being brought into Italy from sub-Saharan Africa via Portuguese markets. This interest in white skin — although present through the Middle Ages as well — takes a different turn in the 16th century, when you start to get much larger black populations in European cities for the first time.

Understanding beauty culture in context

Beauty culture is complex. It is related to broad social forces and to the availability of things like ingredients. It is related to geographical change, economic change.

© Pexels

© Pexels

Today, as in the Renaissance, what happens in the privacy of people's bathrooms or dressing rooms or bedrooms, and how they feel about themselves in relation to the world, is a product of many different factors. These are not personal decisions. As much as we like to think of them as just personal and intimate decisions, they interact very closely with much larger questions and a much larger world.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about the Renaissance’s impact on beauty today

Burke, J. (2024).How to be a Renaissance woman: The untold history of beauty & female creativity.. Wellcome Collection.

Burke, J. (2018).The Italian Renaissance nude. . Yale University Press.

Burke, J. (2004).Changing patrons: Social identity and the visual arts in Renaissance Florence.. Penn State University Press.

Burke, J. (2012).Rethinking the High Renaissance: The culture of the visual arts in early 16th-century Rome.. Routledge.