I started my research on science fiction in the early 20th century in China, Japan and the Soviet Union because I was interested in why their stories were so different. One of the main things that caught my attention, right from the beginning, was a greater prevalence of utopian writing. Rather than the usual kind of dark and gloomy stories about a post-apocalyptic future that seem to be common fare for science fiction today, they often talk about a glittering, post-scarcity future where people live forever and so on. I wondered how we might explain this difference of attitude towards the future. Furthermore, what is the future, anyway? They were talking about time periods that could be 25 years or 2,000 years into the future. I wondered if some of the differences that I detected between, for example, a North Asian vision of the future beginning in the Soviet Union and ending in Japan in the Far East, and many places in between, maybe had something to do with the fact that they were outside Western Europe and North America but were never colonized.

Interwar science fiction and modern culture

Handa Chair of Japanese-Chinese Relations

- North Asian writers of the early 20th century often saw disruptive technology as a potential path to utopia rather than doom, contrasting with the predominantly dystopian Western outlook.

- Their visions of future warfare centered on single, decisive technologies like death rays, engineered plagues or mechanized armies that would render conventional military strength irrelevant and directly threaten civilian populations.

- Hirabayashi Katsunosuke argued that modern culture is shaped by engineers and technology, anticipating Walter Benjamin’s ideas and insisting that new media would expand rather than exhaust human imagination.

- The pragmatic, largely non-theological response to radical technologies in the Soviet Union, China and Japan helps explain their quick adoption of innovations and willingness to reshape society around them.

Utopian not post-apocalyptic

© Aaron Moore

Links across Soviet Union, China and Japan

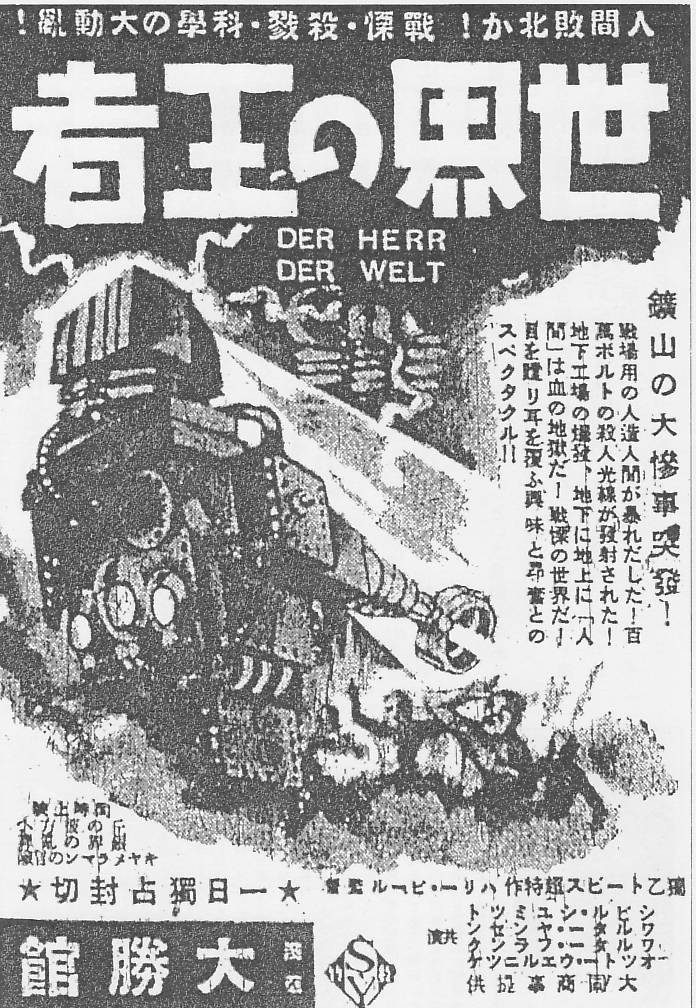

They really believed in the possibility of new forms of science and technology for completely disrupting the world order. That should not be so surprising, because many of them were the recipients of violence enacted by new forms of science and technology in the 19th century. They already knew that a discovery somewhere in Britain, New York, California or Paris could have immediate consequences for who holds power and who gets to determine how the world is ordered. If that is your baseline assumption about how the world works, it stands to reason that you would want to know what future technologies would do to the world. It is really not so fantastic to think of something like a death ray, which would destroy an entire city from a distance, dreamed up by someone like Nikola Tesla. People experimented with these weapons. They were reported in the news all the time. One element of this that often gets forgotten is that for a person in Japan, China or Russia, when they read about things happening abroad, they do not travel; they do not get on a jet aircraft and land in New York City six hours later. It is very difficult to ascertain what is fact and what is fiction.

Imagining modern warfare

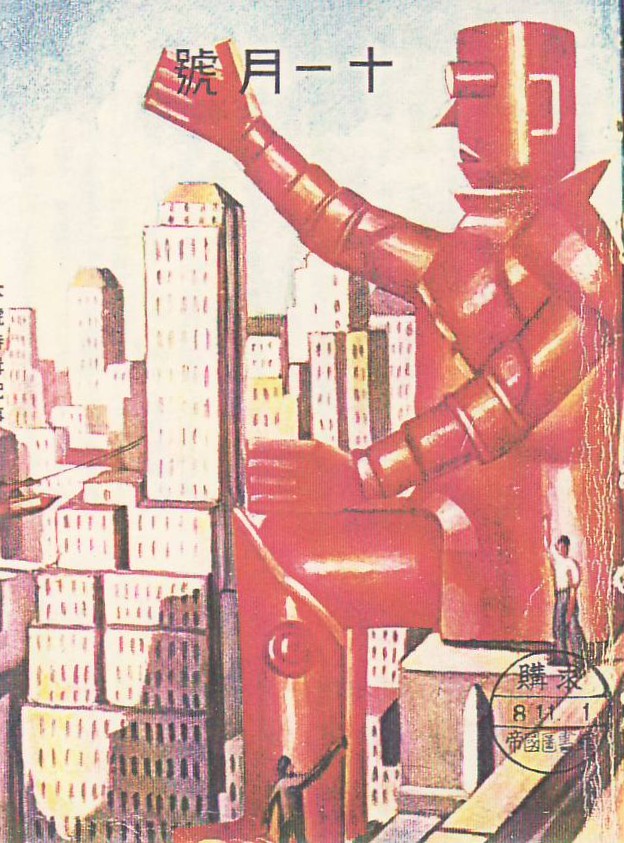

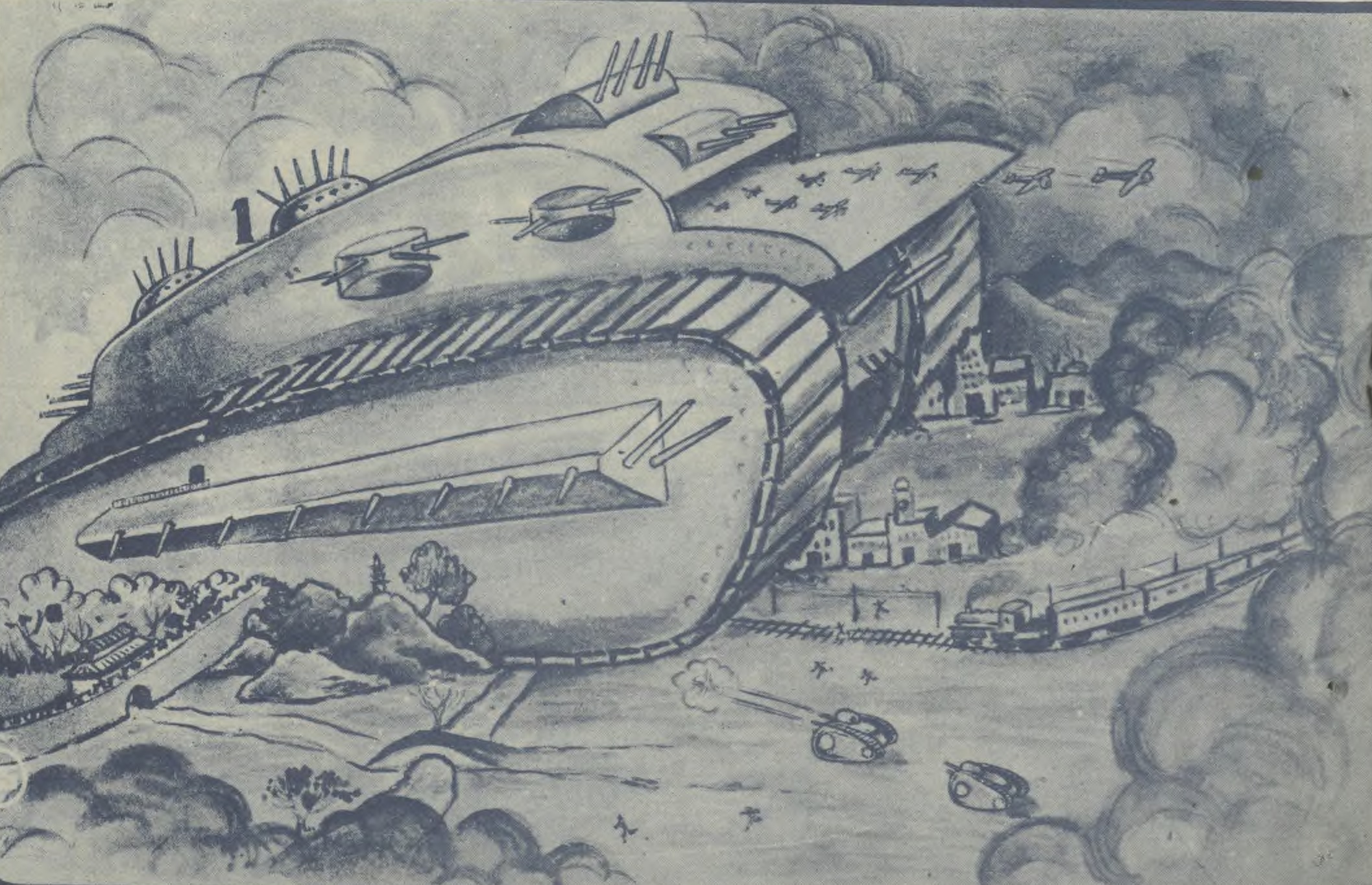

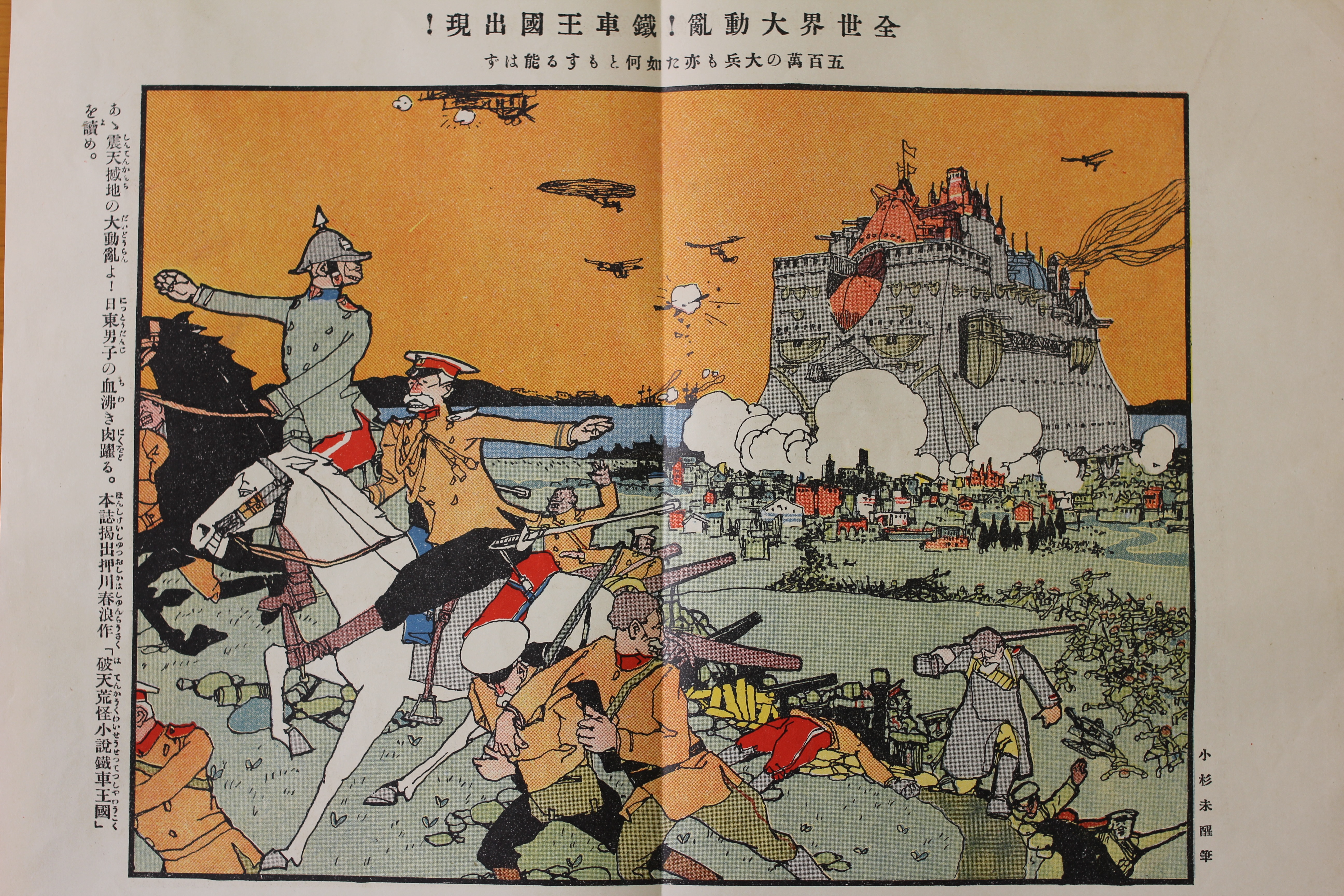

Because these things are mixed together in the same publications, it opens up a vista of envisioning a future that has greater plausibility than many science fiction films today, which audiences can just dismiss as pure fantasy. When they think about the future of modern warfare, it often involves whatever sciences are considered important at that time. If you look at the 20th century, the 1930s, for example, it may have to do with new forms of radiation that people are interested in, or atomic power. Going back into the 1920s, it may have more to do with engineering, aircraft carriers or even flying cities. Going further back into the 19th century, it might have more to do with chemistry. They might be interested in generating new forms of high explosives or even artificial people, being able to harness the powers of chemistry and biological sciences in order to produce a manufactured human that can withstand high thresholds of pain, does not need sleep, does not need food, or some other sort of fanciful depiction of the future.

Underlying fears

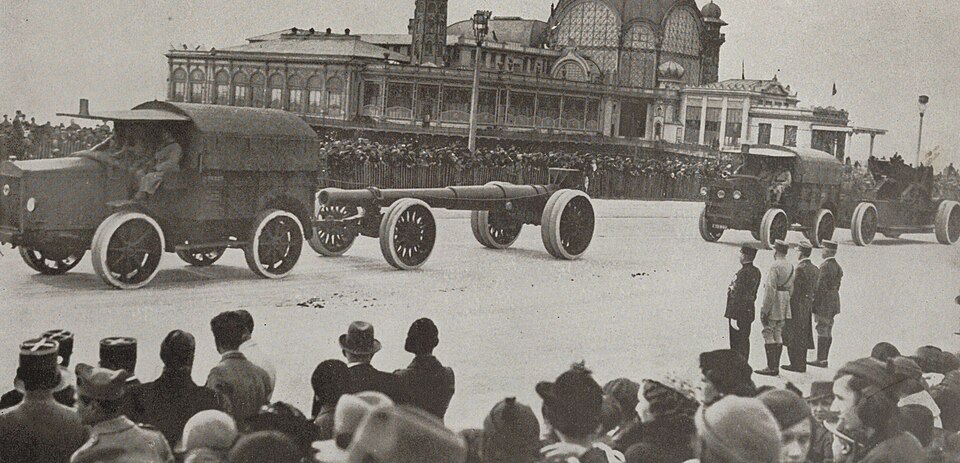

If you look at the depiction of future warfare in science magazines and science publications from the 1920s and 1930s, they pick up a few main topics. One of them is mechanization, so they really see future warfare revolving around aircraft, ships, tanks and rocketry.

© Aaron Moore

© Aaron Moore

The other thing that they are interested in is biological and chemical super-weapons — being able to deploy gases or diseases that can wipe out entire populations or armies, or simply make them sick enough that they cannot fight. Many of these visions revolve around the idea of a single disruptive technology that is going to be introduced on a large scale. Once that happens, it does not really matter how many soldiers you have or how patriotic you are; the science and technology simply wipe you out, and then you become a slave race to a foreign nation. There is a totalizing aspect to their visions of future war, in addition to the fact that they always assume that the civilians of a country will be targeted by these weapons.

Contrasting science fictions

My overall impression of the difference between Western science fiction and the science fiction that comes from North Asia is that people in Europe and North America were more inclined to look with fear and trepidation into the future; people in the Soviet Union, Japan and China, however, are slightly more inclined to look at the future as one in which science and technology unleash disruptive forces with unpredictable results that can be positive in their outcomes. I have a working theory for why this happens.

© Aaron Moore

© Aaron Moore

If you lead a good life, and you have wealth and live in a country that is powerful and wealthy, you have a lot to lose if the world order is disrupted. Consequently, you have more to fear. Whereas if you are living in a country that is oppressed, or you feel personally aggrieved about your situation, you may feel that disruptions to the world order could benefit you. You can also see this within each national context: people who feel like the world order should be changed are more inclined toward more utopian storytelling, and people who feel that their position is threatened by change express more anxiety about the potential disruptive effects of science and technology. There is an implication behind what I am saying that I think we should all be thinking about. If the science fiction that we have today is predominantly dystopian — as in, it is dark, involves zombies, computer viruses, out-of-control AI or killer robots — maybe we are living the best lives we possibly can right now. Maybe this is the closest we will get to paradise in the human experience up until this point. If that is the case, that in and of itself is slightly concerning.

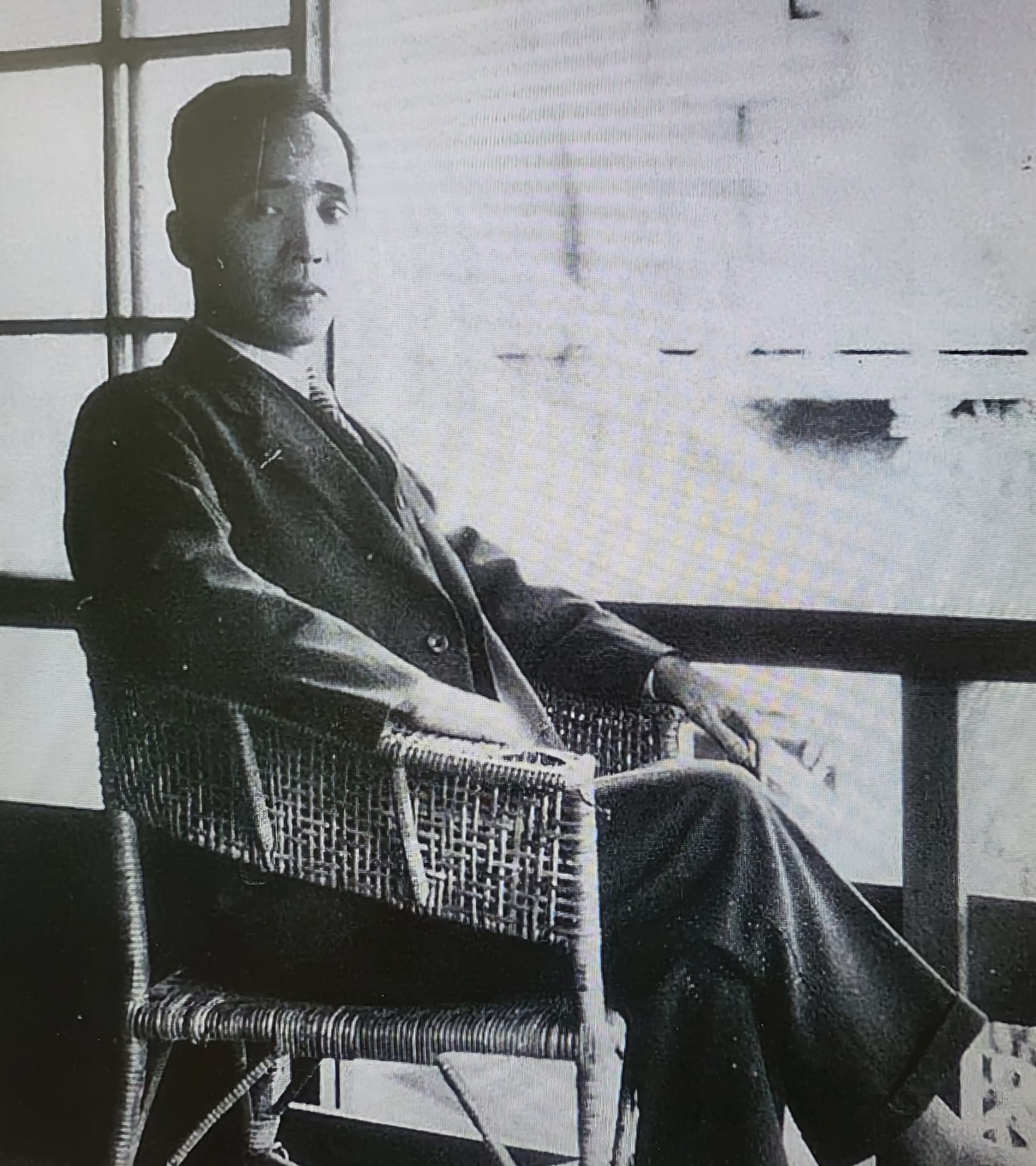

Rediscovering Hirabayashi

Hirabayashi Hatsunosuke was one of the most important intellectuals in interwar Japan, and it is a shame that he is not more widely known today.

© Aaron Moore

© Aaron Moore

He believed in what could be perceived and touched and studied by empirical science, but he also came of age in the interwar era, in which Japanese Marxists were attempting, as Marxists were everywhere, to explain culture as a product of class consciousness. Romantic literature came about because of a bourgeois revolution, as the old landed gentry and the feudal classes had their literature and arts, and so the proletariat and the working people would produce their culture as soon as they had their consciousness. Hirabayashi made a very interesting intervention into all of this and said, take the case of cinema. Which class owns cinema as a cultural product? In fact, none of them do. In his age in particular, in the 1920s, the Soviet Union was doing remarkable work with cinema, as were the Americans — and how much more different could you get than the capitalist United States and the socialist transformations going on in Russia? Yet, they were both innovating this art form. Hirabayashi says that 'culture in the modern era is a product of the engineer's hand' in his famous essay on technological revolution in the arts, which anticipates many of the same things that are heard in Europe a bit later, coming particularly from Walter Benjamin. If science and technology can produce new forms of culture that are not about class consciousness and are not coming down from the heavens in some sort of spiritual or transcendent way, then what does that mean for cultural transformation? What actually is culture, in that case? I think Hirabayashi was very confident in many ways that science and technology would open up, often unintentionally, new forms of social formation that we had not anticipated before.

For example, in his essays on women, he said, why do you see women everywhere in society today? Japan traditionally did not necessarily have women working in cafés or working on trains. He said basically capitalism hits a point in its development where it needs additional labor, and the only place it can find it is by pulling women out of the countryside and putting them to work. It is not the suffragettes; it is not the parliament; it is not liberation movements; it is the desire for capitalism to find new forms of exploitable labor. We do not have to narrate this necessarily as a dire consequence. In fact, what you end up having are women who now have disposable income and are fully fledged members of modern society. There is a great example of how technologies like the railway, the telephone exchange and the cinema can bring women into society in an entirely new way and start to restructure gender relations. Hirabayashi had a very almost utopian vision of where the world was going.

Technology and imagination

I will just read a brief excerpt from a remarkable essay that he wrote called Literature 50 Years in the Future. He writes:

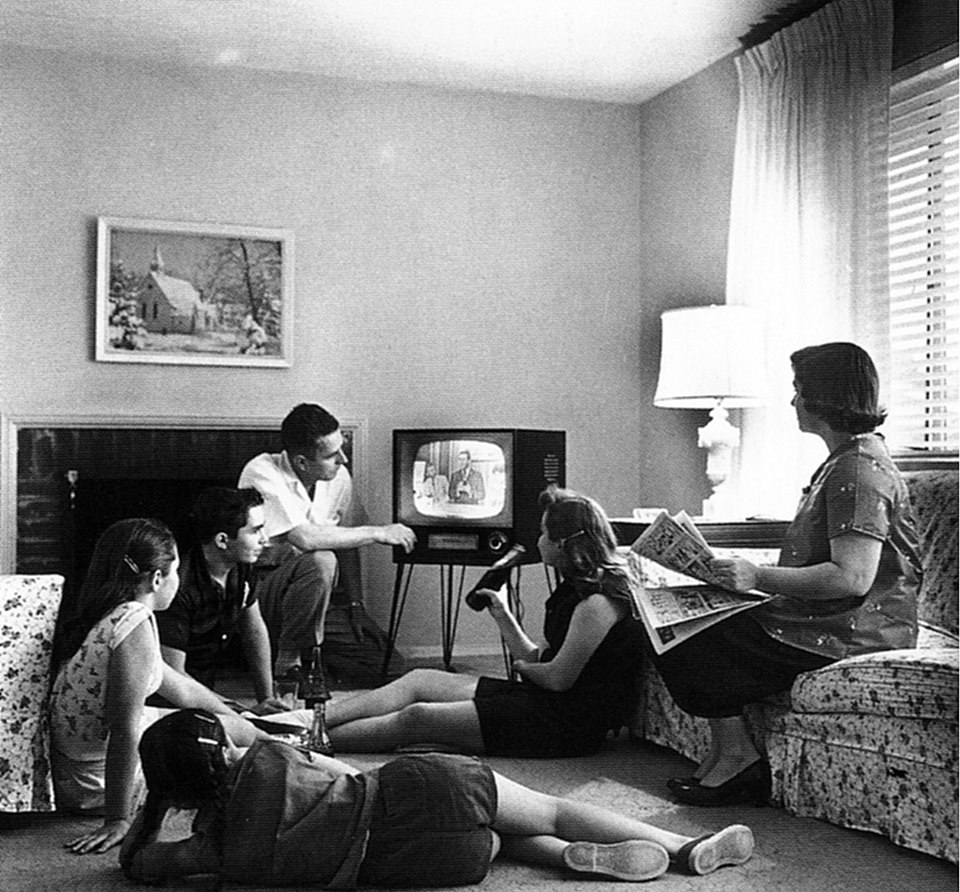

© Evert F. Baumgardner

© Evert F. Baumgardner

"There may be some people who think that the consequence of making sound and color sensible and the electronic transmission of images," and here, of course, these mean television, which was not a technology in the 1920s yet, "will render every place on Earth immediately visible and audible and therefore will anesthetize our power of imagination. But that fear is as unfounded as barbarians looking on civilized people of today and thinking the same thing. Perhaps we are gradually conquering the world of fantasy by making it a reality. But I do not worry about us exhausting the source of human imagination as we continue to expand our world."

Let me put it this way. If you brought Hirabayashi into the 21st century and said to him, do you not think artificial intelligence is going to destroy arts and humanities? He would say, no. It will irrevocably transform it, as I see it, transforming history and literature and art, but it can never actually exhaust the human imagination. It will simply restructure our intellectual lives, our society and our culture in a way that will be unrecognizable 20, 30, 50 or 150 years into the future.

Hirabayashi and Walter Benjamin

The fact that Hirabayashi and Walter Benjamin could develop almost exactly the same ideas without ever having conversed with each other suggests that this is not a development of genius in Europe that gets transmitted all over the world but rather a fault with the way that we construct necessary readings in course syllabi, for example. It shows that Japanese people, Chinese people and Russian people, as well as people in France, Germany, Britain and elsewhere, were confronting similar problems with modernity. One of the major problems that we have with the history of something like science fiction is that it gets separated not only between East and West but between science and fiction. Japanese people at the time did not really suffer so much from this problem, because scientists and engineers, military leader and political figures and writers and artists often conversed with each other in a fairly salon-like way.

© L’Éclaireur du dimanche illustré, N° 499

© L’Éclaireur du dimanche illustré, N° 499

In the same way, Hirabayashi is not Japan's Walter Benjamin any more than Walter Benjamin is Germany's, Europe's or America's Hirabayashi, even though technically Hirabayashi published before him. It is simply a matter of two intellectuals facing the same problem, and if they are perceptive enough and they are brilliant enough, as these two men were, then it should not surprise us that they arrive at the same solution. When we want to approach these larger problems of technology, media and modernity, before we make strong normative arguments — modernity is this, or science and technology's impact on society is that — we should be sure that these phenomena occur broadly across the globe in every context where they are relevant, rather than taking one country as a normative case study.

Impact on tech adoption

One of the questions you might want to ask about the emergence of science fiction in the 1920s in the Soviet Union, China and Japan is: does it give us any kind of presentiment for the powerful transformations that lead the Soviet Union to be a global power; or China to be a global power; and Japan to be, if not a superpower, certainly a very influential nation?

© Aaron Moore

What I can say is that the reaction that these countries had to new forms of knowledge in the 19th and 20th centuries may give us an indication of why their leaders and what I call their visionary class — the people who come together to project a vision of the future and then try to take action in the present to actualize that future — took the direction that they did. One of the principal factors here is that when disruptive science and technology came to these countries, you did not see a massive reactionary force against them. It was very alarming and very disturbing, but, for example, if we take the case of the vision of artificial people — that one day humans would be manufactured in a factory or some other kind of facility — and the implications of such a technology, people in China, Japan and the Soviet Union largely did not bother themselves with theological or philosophical quandaries about this. Certainly, there are concerns about what it would do to the labor force, what it might do to gender relations, how it might transform modern war, but very rarely in the texts of that period do you see someone saying, this will be an offense to God, or, do these people have a soul? That sort of preoccupation seemed to be more aligned with reactions in other parts of the world, including within Western Europe and the United States. Maybe this gives us a clue as to why technologies were quickly adopted within these countries: they took a fairly practical and materialist worldview to the introduction of foreign knowledge.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

science fiction in North Asia

Moore, A. W., & Jacobowitz, S. (Eds.). (2025). The Hirabayashi Hatsunosuke Reader: Mass Culture and Intermediality in Imperial Japan . Bloomsbury Academic.

Moore, A. W. (2025). Seeing the future: Four stages of Japanese science fiction’s literary development, 1870–1937. Il Giappone.

Moore, A. W., & Jacobowitz, S. (Eds.). (2025). Literature fifty years in the future. In S. Jacobowitz & A. W. Moore (Eds.), The Hirabayashi Hatsunosuke Reader: Mass Culture and Intermediality in Imperial Japan. Bloomsbury Academic.

Moore, A. W., & Chen, T. M. (2012). The Asian machine. Cultural Critique, 80, 1–10.

Benjamin, W. (1969). The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. In H. Arendt (Ed.), Illuminations (pp. 217–251). Schocken Books.