Greenhouse gas emissions are sitting at the bottom of the atmosphere, essentially creating a layer or a trap that does not let all the warming that happens on the earth to diffuse outside of the planet. This means that all these emissions are essentially creating what people call the greenhouse gas effect, which magnifies, for example, the potency of hurricanes, magnifies the speed of a drought and magnifies how heavy rains can be, causing a flood. All of these issues, not to mention the rise of temperatures, are obviously big risks for human life.

Climate change regulation

Professor of Political Science and International Relations

- Mitigation and adaptation are complementary pillars of climate action, and both must advance at the same time to manage existing impacts while cutting future emissions.

- Carbon taxes and cap and trade dominate mitigation debates; both can curb emissions effectively yet provoke political resistance — the former over taxation and the latter over rising allowance costs.

- A “just transition” requires climate policies to confront social inequities so that women, racial minorities and other vulnerable groups gain real opportunities in the emerging green economy.

Need for climate change policies

We need climate change policies because we need governments to tackle the issue of greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to the change of the climate as we know it.

© Bas Meelker

© Bas Meelker

Only through regulation, only through monitoring and maintaining a stable climate, can we deal with the issues climate change is causing, which are extreme weather events and magnified natural disasters.

Designing climate strategy

Broadly speaking, when we think about climate policies, we either think of what we call climate mitigation policies, which are essentially policies that try to reduce carbon emissions or to do what we usually call decarbonization, or otherwise we think about adaptation policies, which are essentially a way to talk about the management of the consequences of the crisis that climate change magnifies.

© Pexels

© Pexels

There is a lot of debate on climate change policies. In fact, there is probably more debate about how climate policy should be designed than on whether climate change is happening or not. Countries disagree among themselves and within themselves on how best to design them.

A combined approach

Mitigation policies and adaptation policies, from a technical standpoint, come together. They should not be thought of as two opposite goals of climate action. The IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, for many years — in fact, decades — has suggested that the two need to be applied simultaneously. On the one hand, we do need to reduce emissions, and we need to think about how the new economy of the future will look (one that will generate fewer emissions), while also adapting to the fact that, at this point, we have accumulated a lot of emissions that are changing and have, in fact, changed the climate.

© Pexels

© Pexels

We need to adapt. That said — and this is where politics comes in — a lot of the political debate around climate policy often juxtaposes mitigation policies and adaptation policies, almost as if they are two oppositional goals of climate policy, and many different ideological factions have actually sided with either mitigation policy or adaptation policy.

Taking climate policy seriously

We need to be thinking about mitigation and adaptation policies together. There is a lot of debate about the fact that we may be too late doing mitigation. We may need to move only to adapt, and vice versa. There is a technocratic mindset that thinks that it is all about mitigation and that adaptation is just too difficult to deal with, and I believe that we need to be true to both dimensions, both aspects of climate change. I hear far too often in political debates that this is either-or. It is a zero-sum type of logic. Taking climate policy seriously means bringing both together to the forefront and doing them both simultaneously everywhere.

Mitigation policy

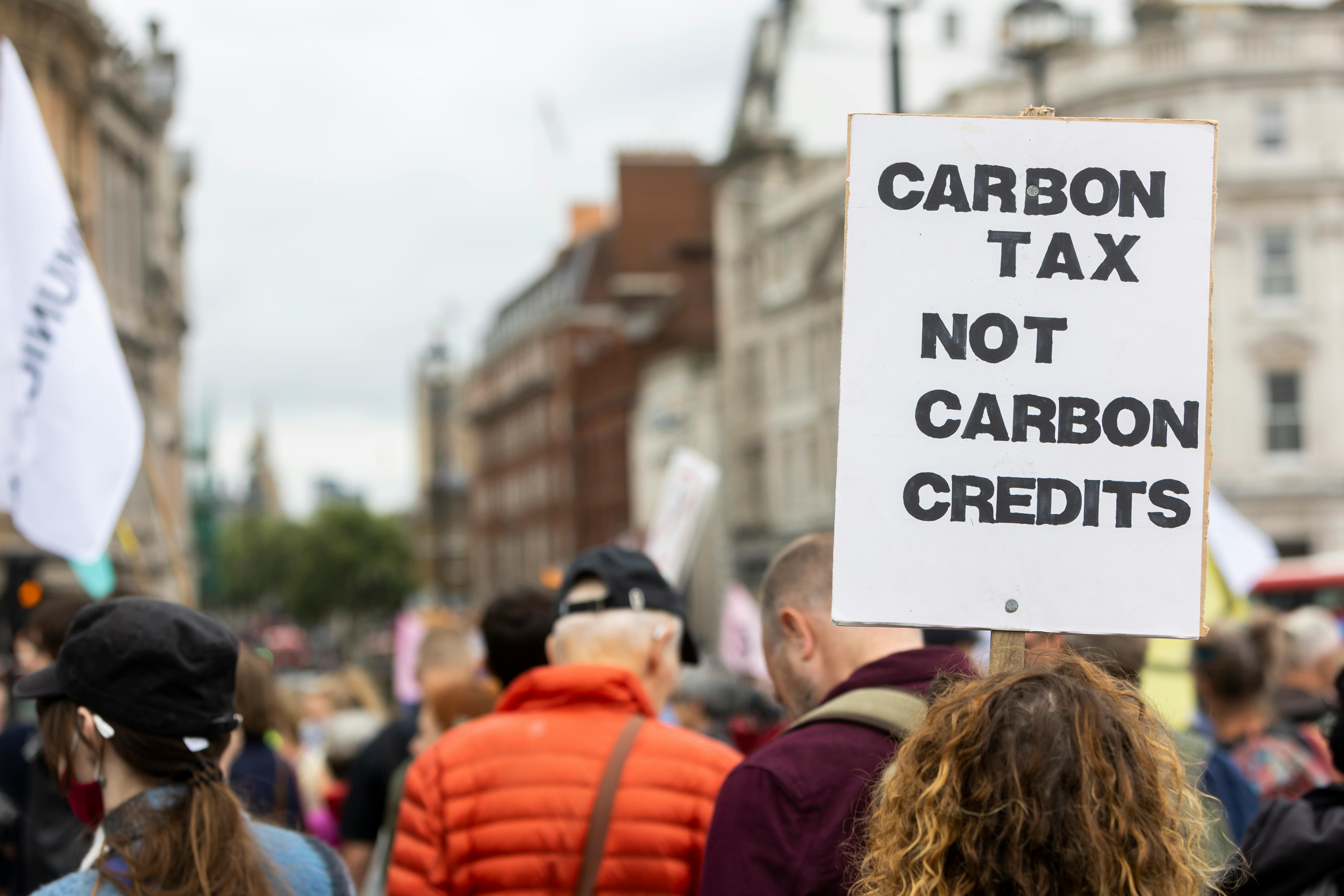

Mitigation policy has been, in some ways, the fulcrum or center of climate policy debates for the past 20 years. These policies can materialize in many ways, but usually they manifest as carbon taxes or as cap and trade. Carbon taxes are, as the phrase indicates, essentially fiscal levies, taxation policy, that put a limit on how many tons of carbon can be emitted. Governments usually attach a fee to a ton of carbon that can be produced.

Cap and trade is a different type of policy. It is a policy that is more flexible; the cost is slightly more diffused. The idea is that there is a limit (cap) to how much carbon there can be in a system, and then the actors that engage in that system — and again, usually we think about cap and trade just like a trade system, a market — can trade licenses or allowances for emitting carbon. This incentivizes the greener actors, the greener firms, for example, to receive more money from the dirtier firms that then need to provide them with allowances in order to continue polluting. These are two very different types of mitigation policies, both of which have been tested in many countries. They have various levels of effectiveness and different political implications.

Carbon taxes or cap and trade?

© Pexels

© Pexels

Carbon taxes have been described, especially by environmental economists, as the most effective type of carbon policy. To some extent they are, because they are the most obvious type of climate policy. It is usually a pretty straightforward, one-figure type of policy; it is not very difficult to design, although it can be difficult to monitor. Generally speaking, especially in states that have enough fiscal capacity, they can be very effective. The problem is that not a lot of people like taxation and that the politics of taxation, specifically carbon taxation, can be incredibly hard to digest.

Cap and trade, on the other hand, because it is more flexible, does not generate the same type of toxic politics that carbon taxes tend to generate. Cap and trade and carbon markets are much more about training the actors that get regulated (such as polluting firms) to think about the externalities that their production causes, like emissions. The problem with cap and trade, though, is that often it is only meant to start with a low bar, with cheap allowances and low levels of carbon to regulate; eventually, across time, they can go up. This going up is usually what firms do not like. Even if it is a more flexible mechanism, cap and trade can also be politically toxic and can be captured by interests that do not like it.

Green subsidies and green industrial policy

The mitigation policies that rotate around carbon taxes and cap and trade are very much market-oriented regulations, while green industrial policy and green subsidies are very much the state taking resources that have been collectively contributed and injecting them into building the green industry of the future.

Recent examples of this type of green industrial policy approach to climate policy are the Green Deal in the European Union or the Inflation Reduction Act that existed until recently in the United States under the Biden administration. These have been massive efforts by democratic governments to inject money for the purpose of building the future climate champions among businesses in Europe and in the United States.

The point of green subsidies and green industrial policy is to beef up the competitors of fossil fuels, which would be clean energy companies, clean tech and renewable energy assets.

Adaptation policies

Adaptation policies have historically been the Cinderella of climate policy, partly because, for a long time, adaptation seemed to be an issue only for the most vulnerable countries, and partly because adaptation politics are actually harder than mitigation politics. Adaptation policies are essentially the policies that try to manage the fact that the climate crisis is here to stay and that we need to deal with an increased frequency of natural disasters, extreme weather events and increasing temperatures.

© Pexels

© Pexels

Adaptation policy at the local level would be, for example, infrastructure investment. In the United Kingdom, a lot of adaptation policy has to do with flood prevention or prevention of further sea-level rise and coastal erosion. Adaptation policy is very expensive. It does not mean that it is not effective — in fact, you would rather live in a world in which there are adaptation investments and strong adaptation policy rather than not — but it is, relatively speaking, much more expensive than mitigation policy. Adaptation politics can be equally, if not more, toxic than mitigation politics, because we are essentially all losers of climate change. Exposing the fact that we have not invested enough in adaptation means that we are all at risk of suffering from climate change.

Adaptation policies can be preventive, so they can try to build infrastructure, for example, in prevention of the amount of sea-level rise that we expect in 10, 20, and 30 years from now; they can also be reactive. The building of housing in the follow-up to a major flood is a reaction to the fact that probably a lot of homes were lost in previous floods. There has not been enough investment at the global or local level on adaptation to make adaptation policy only preventive at this point. There is a lot of reactive adaptation policy happening, some of which will end up being about managing the potential refugees of climate disasters or the potential dislocated households that will suffer from climate events. Adaptation politics is essentially the residual effect of mitigation policy to the extent that it is dealing with all the consequences that climate change will throw at the earth and global society as we know it — consequences that do not entail just decarbonization.

A just climate transition

Essentially, thinking about a just energy transition or a just climate transition forces us to think about the social community-level dynamics that need to be taken seriously if we want democratic, bottom-up public buy-in. The key word in "just transition" is obviously "just". In other words, there is a lot of emphasis on the fact that there needs to be explicit justice embedded in the way in which we design mitigation or adaptation policies. It is essentially a bag for thinking about the social, human dimension that, otherwise, has been dismissed for many years of climate policy that was way too technocratic, way too top-down and way more legalistically than sociologically thought.

© Pexels

© Pexels

We do not live in an equal society, and dismissing the fact that the most vulnerable would suffer from an energy transition means taking away various sections of society from being active participants in the energy transition. We know that fossil-fuel sectors tend to be more populated by men historically. This is, in a way, a product of legacies and historical path dependency. In a world in which we want to have more renewables and more clean technology, in which jobs are more embedded in the clean sectors, we need to make sure that we let not just men but also women participate, if we want to solve otherwise very deep structural inequalities in society. The same goes for racial communities that have historically been more embedded in some fossil-fuel sectors.

Challenges for future climate policies

In some of my research in the United States and India, it is quite clear that there is ethnic and racial diversity in the communities that are more exposed to climate-change effects themselves. For example, the most exposed coastal communities in the south of the United States tend to still be black communities and black rural villages. Many of the forefront workers in coal in India are migrant daily workers who do not necessarily have the same identity as some of the richer communities for which they work. We need to address the fact that the new future economy that is embedded more in clean assets and that takes climate change seriously does not do it just by essentially substituting the work in fossil-fuel sectors and injecting it into, for example, renewable sectors. We do need to bring with us all those minorities that the fossil-fuel economy has actually excluded or has made vulnerable. That is what, ideally, a just transition will look like: bringing those minorities and groups at risk with us and embedding them in the future economy.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

climate policy and climate change regulation

Genovese, F. (2020). Weak states at global climate negotiations. Cambridge University Press

Gaikwad, N., Genovese, F., & Tingley, D. (2022). Creating climate coalitions: Mass preferences for compensating vulnerability in the world's two largest democracies. American Political Science Review, 116(4), 1165–1183.

Genovese, F. (2019). Sectors, pollution, and trade: How industrial interests shape domestic positions on global climate agreements.International Studies Quarterly, 63(4), 819–836.

Genovese, F., & Bayer, P. (2020). Beliefs about climate action consequences under weak global institutions: Sectors, home bias, and international embeddedness. Global Environmental Politics, 20(4), 28–50.