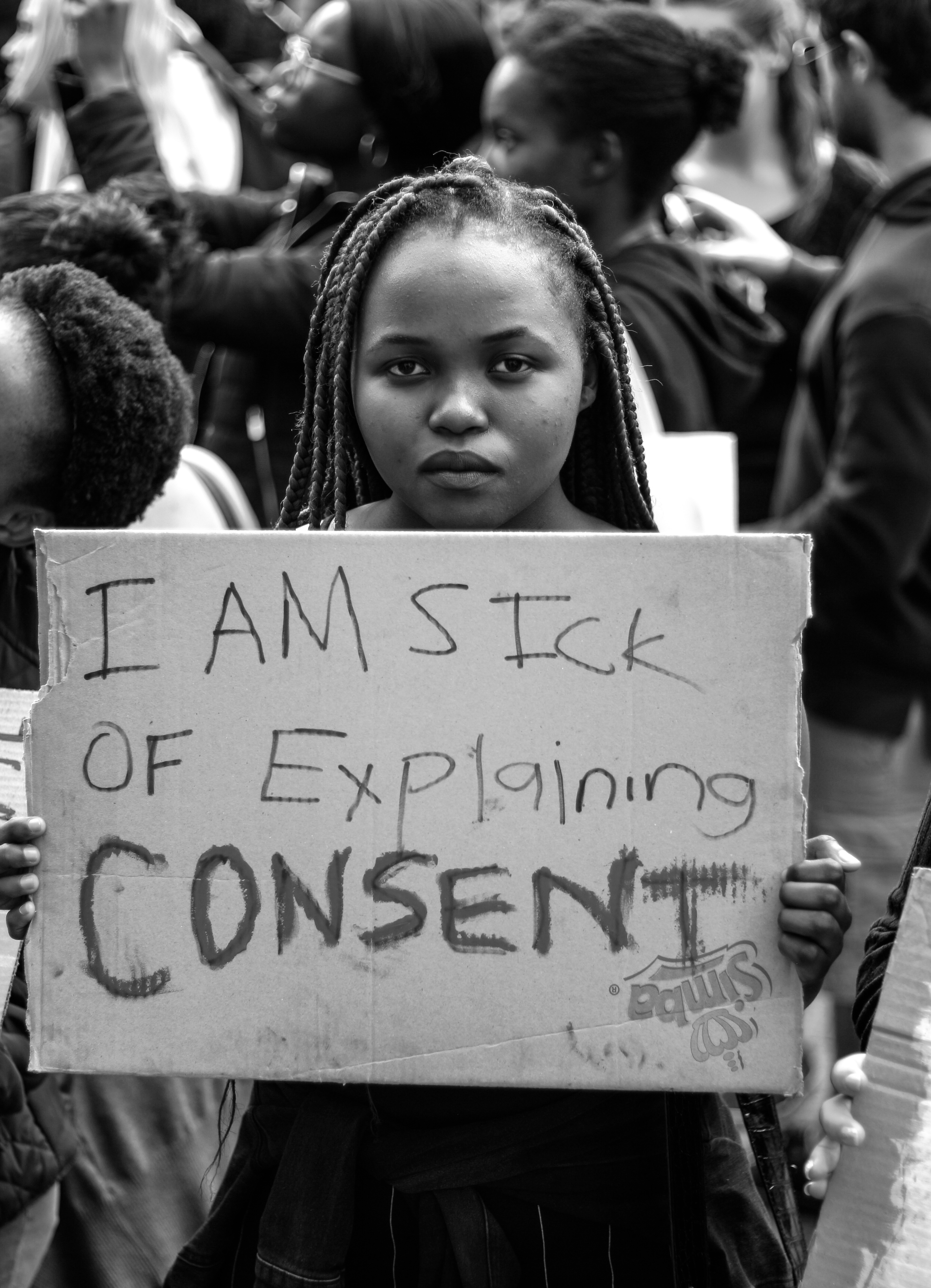

The fourth wave, which is currently underway, began in the 2010s when a lot of people were saying, “Feminism is over. It’s accomplished. What else is there to do?”, which, of course, was not at all correct. There has been an explosion, from that year onwards, of youth movements and protest movements across the world. A very important part of this is not only young women joining in those movements but also developing their own forms of organisation. There was a new vitality brought into feminism by a generation of young women activists who were taking to the streets in huge numbers around issues of violence against women, reproductive rights, and having enormous success in organising these protests and in pushing forward a platform of demands – in many cases, radical demands that extend the feminist purview to include LGBT struggles, Black struggles and a whole range of other struggles, including, very importantly, environmental issues. It’s striking to see, for example, Greta Thunberg, a young Swedish feminist who at 16 years old became symbolic of a new kind of young woman taking a very active role in international politics.

Feminist activism across the generations

Professor of Sociology

- Feminism has generally been seen to have pursued three prongs of struggle: social justice, rights and political representation.

- First wave feminism: In the early 20th century, there was the very first attempt to create international feminist organisations.

- Second wave: The 1970s saw a new wave of feminism which was far more radical: feminists began to question the whole cultural set-up in their societies and to demand cultural change, as well as structural change.

- Third wave: This is known as a period of institutionalisation, where there was more activity to bring about legal change and to advance a programme of women’s rights in the fullest form.

- Fourth wave: There was a new vitality brought into feminism in the 2010s by a generation of young women activists.

First wave feminism

The first thing to say is that feminism emerged in the period of the Enlightenment as a movement – a radical movement – for equality, rights and justice. In the 18th century, there were significant debates about rights: the American Revolution, the French Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man, for example, as well as debates about the emancipation of slaves and the emancipation of women.

The 18th century was the beginning of the discussion about women’s place in society. Women were beginning to demand their own rights and, indeed, when the Declaration of the Rights of Man was issued during the French Revolution political activist Olympe de Gouges produced the Declaration of the Rights of Woman – for her pains, alas, because she was a monarchist, she ended up on the guillotine. Nevertheless, the issue of women’s rights was taken up and continued to be a major concern throughout the 19th century, when the very first feminist movements were beginning to put together sets of demands for women to be recognised as full human beings with full rights. The period of the 19th century was, therefore, the inception of feminism and the birth of those first women’s movements making demands for suffrage, for the right to have an education and the right to enter the professions.

The 20th century saw the continuation of that first movement known as the first wave of feminism. There was the very first attempt to create international feminist organisations pushing for rights, equality, citizenship and justice, ideas that travelled to most parts of the world: women in Japan calling themselves The Blue Stockings, demanding the right to education, and Latin American women demanding suffrage. In the more radical sectors of feminism, like the anarchist movement, women were demanding sexual justice; that is, not to be treated as victims of the double standard, not to be controlled by men, not to have their sexuality undermined and denigrated. The gains of that first wave were slow at first but gradually spread through society and through to other parts of the world.

Second wave feminism

There were some gains of the first wave feminism, but the 1970s saw a new wave which was far more radical in some ways; not that earlier feminism didn’t have any radical currents – it had the socialists, anarchists and libertarians living in communes and so forth – however, in the 1970s, feminists began to question the whole cultural set-up in their societies and to demand cultural change, as well as structural change. They added to rights for equality, for example, changes in education, as well as in the law, that would bring tougher sentencing to those who were perpetrators of violence against women. These were themes that were able to be developed over the following 40 years and are very important in women’s movements today.

Photo by Bohemian Photography

Third wave feminism

After the second wave, many feminist women entered into organisations, governments and the justice system. This was known as a period of institutionalisation, where there was more activity to bring about legal change and to advance a fuller programme of women’s rights. The culmination of this were the four conferences that the UN held in order to push forward on human rights programmes. The women’s movement was very active in them, and what we see coming out of this activism – not just in the West, but across the world – was a series of meetings in which women tried to develop and push forward a programme of women’s rights. This began with the most radical of body of law, which was the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which was ratified in 1979 and came into force in 1980. The law committed states to report on progress, and it was signed by almost every state in the world, providing a platform for women in various countries to advance, to lobby for more progress and, of course, for implementation, which was extremely important. Laws have to be implemented and resources are needed in order for them to have effect.

The third wave, therefore, saw significant advances in legal rights. The Beijing conference that brought the UN talks to an end mobilised over thirty thousand women from different parts of the world to debate on Platform for Action, which meant encoding the CEDAW legislation into a policy platform that was to guide the work that would go in the policy for years to come.

It’s worth mentioning that many feminists felt that the entry into institutions had sapped some of the vitality and grassroots creativity out of the movement. As a result of some of those feelings and perhaps divisions within women’s movements, there was a period of latency; although, at the same time, in the 1990s, we saw the emergence of very new actors – indigenous and popular women in Latin America, Black women and women in different sectors – who started to become clearly visible in demands for justice.

The fourth wave

Photo by MF Orlean

The three pillars of feminism

Feminism has generally been seen to have pursued three prongs of struggle. In the first place, a demand in the form of symbolic justice to stop the harm of non-recognition that denigrates women, the forms of misogyny and social norms that continually work against women. One only has to think of campaigns that went on 20 years ago against certain kinds of advertising or the topless young women of page 3 in certain UK newspapers.

A second prong has been to try to bring social rights more firmly into alignment with women’s needs. I would particularly stress the whole question of care: if women are going to be going into work, which increasingly women have to do and want to do, somebody has to look after the children and elderly, because that work tends to fall in the division of labour to women in most societies, if not all.

Photo by SCOOTERCASTER

Thirdly, there is the question of political representation. Demanding equality for political representation for half of the population would seem to be, in democratic societies, a completely appropriate demand. However, if we look at the statistics across the world, only one in four parliamentarians are women. Furthermore, no country has successfully sustained an equal representation of women for very long. If it is attained, it very often doesn’t continue in that direction.

Where are we today?

One can’t deny that there has been progress, even in societies where laws remain based on patriarchal assumptions in which women are still to a large degree second-class citizens, but we have seen a fair amount of improvement, including in some of the countries of the Middle East, where women’s rights were much slower to develop. So, although we do have a very mixed record of progress on women’s rights, the general picture has been one of slow development towards greater equality.

Discover more about

feminist activism

Molyneux, M., Dey, A., Gatto, M.A.C., et al. (2021). New Feminist Activism: Waves and Generations. UN Committee for the Status of Women Meeting, New York, United States.

Cornwall, A., & Molyneux, M. (Eds.). (2008). The Politics of Rights: Dilemmas for Feminist Praxis. Routledge.

Molyneux, M., & Lazar, S. (2003). Doing the Rights Thing, Rights-based development and Latin American NGOs. ITDG Publishing.

Molyneux, M., & Razavi, S. (Eds.). (2002). Oxford Studies in Democratization: Gender Justice, Development, and Rights. Oxford University Press.

Molyneux, M. (2001). Women’s Movements in International Perspective, Latin America and Beyond. Palgrave Macmillan.

Molyneux, M. (2001). Analysing Women’s Movements. Development and Change, 29(2).