In the 14th century we can also find a striking sense of longing for a time gone by. We do not find the word nostalgia, nor any single word that quite captures the idea, but we do find related phrases such as “the good old days” or “the former age,” and a series of vivid quotations about how much better things used to be. One of my favorites is from a French writer who said, “In my day, when I was young, the kingdom was as rich and as full as an egg.”

Nostalgia in the 14th century

Associate Professor of Medieval History

- The word “nostalgia” was coined in 1688, yet 14th-century writers already voiced a powerful longing for “the good old days,” showing the emotion predates its label.

- Cataclysms such as the Little Ice Age, famine, Black Death, urban growth and rampant inflation made life feel unstable, fueling widespread yearning for a steadier past.

- Nostalgia could reinforce hierarchy, but it also energized uprisings like England’s 1381 Peasants’ Revolt, where rebels invoked a lost age of fairness.

- Sociologist Hartmut Rosa’s idea of “social acceleration” fits the era: when change accelerates, societies repeatedly turn to nostalgic visions, revealing nostalgia’s universal yet historically specific character.

Origins of nostalgia

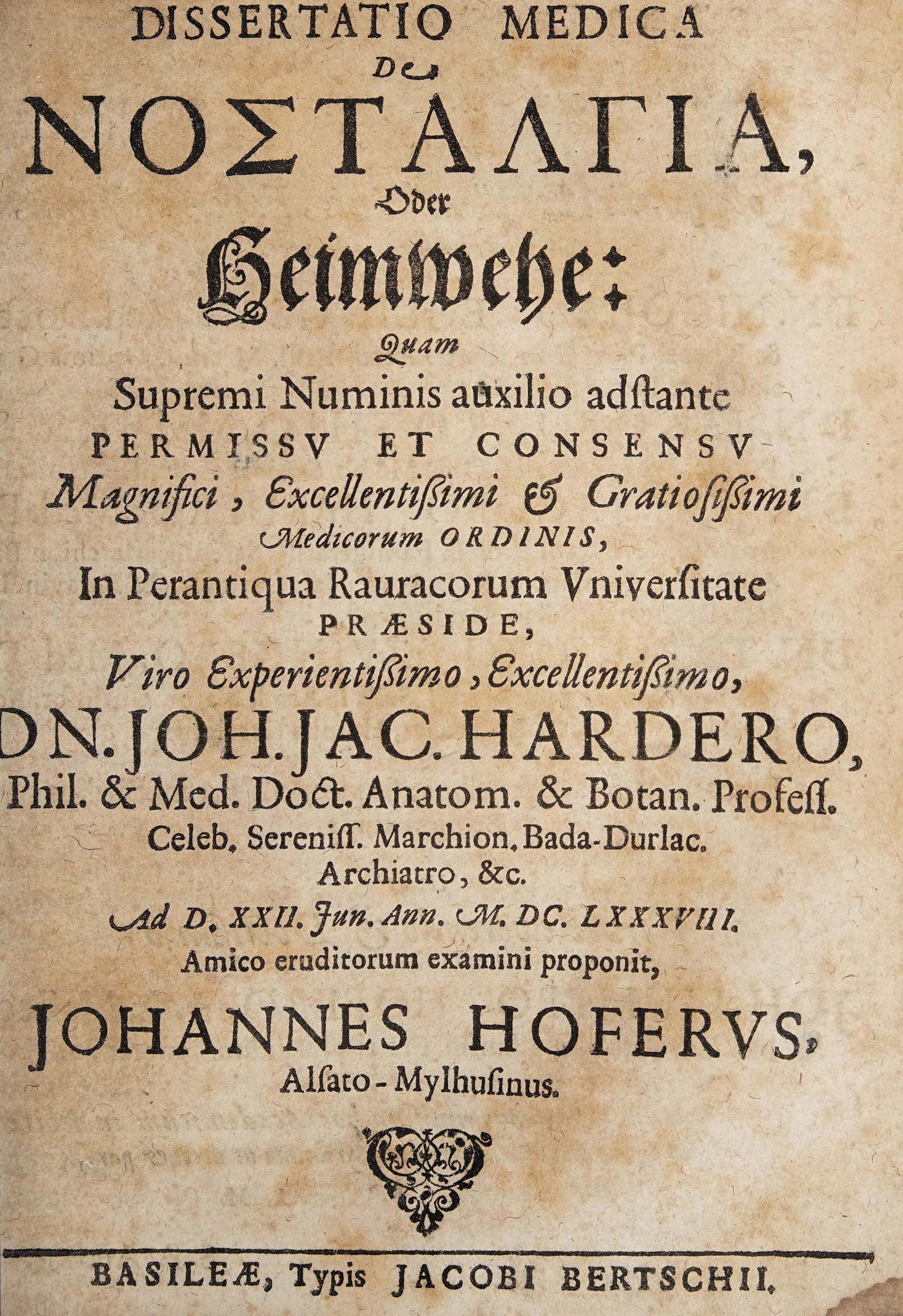

Nostalgia is a word that was only invented in 1688. It was coined by a Swiss physician named Johannes Hofer, who was trying to diagnose an illness that seemed to be afflicting Swiss mercenaries in particular. These mercenaries were getting increasingly homesick and apparently experiencing physiological symptoms of homesickness, because they were so miserable. They were fainting, and one of them even died. Apparently, it would be brought on when they heard the sound of cowbells, which reminded them of home. Hofer decided to create a new term to describe this phenomenon. He took the German term Heimweh and found a Greek equivalent, nostos, and algos, meaning “home” and “sorrow” or “longing”, and put them together to give it a professional-sounding medical ring. It was in the late 17th century that the term was invented, and he was using it to talk about a very specific set of circumstances.

Dissertatio medica de nostalgia, oder Heimwehe © Johann Hoffer, Wellcome

Dissertatio medica de nostalgia, oder Heimwehe © Johann Hoffer, Wellcome

Vaguely nostalgic

In the 14th century, strikingly, people were not terribly precise about what they were nostalgic for. Very often, people seemed to be referring to the days from a couple of generations previously, the days of their grandfathers. If they were very elderly, they might have been referring to the days when they were young.

Historiated initial M depicting the parable of the Good Shepherd © Charles Fournel, Freelibrary.org

Historiated initial M depicting the parable of the Good Shepherd © Charles Fournel, Freelibrary.org

What is really interesting in the 14th century is that alongside this wave of longing for a couple of generations prior – 50 years or so – there was also a longing for an unspecified golden age, a kind of ur period: a former time when things were less corrupt; people were less greedy; people dressed properly; children behaved properly; wars were not being fought all the time; prices were reasonable; politicians behaved properly – a series of tropes which probably sound quite familiar to us. I think the early 14th century is a particularly interesting period because this is the moment of the first stirrings of humanism as well, when people are more emphatically referring to a classical golden age and picking up on writers like Horace, Virgil and Ovid and the sorts of nostalgias that they were expressing. We get this very personal nostalgia for the days of my grandfather overlaid onto this rather intellectualized classical nostalgia.

There is a wonderful set of pastoral poetry, which was discovered in a lost manuscript at the University of Pennsylvania. It contains a series of poems in which the speakers are elderly shepherds talking about how much better things were in their youth. In one of these poems, one of the old shepherds says, “Quant je fu jouvenceaux [...] Je suis de vous li plus aisnez / Mais on ne vi tel desraison”, so, when I was a young man – and then he pauses – I am the oldest of you all, and I never saw such terrible things as now. They go on to describe the ways in which the wolves are eating the sheep now, and everything has been lost. Of course, they are making a series of political points about political turmoil and what has been lost in terms of stability in France.

Calamity evokes nostalgia

In many ways, it is not surprising that we would see a wave of nostalgia in the 14th century. It is a century of a whole series of cataclysmic events. More than this, it is also a century in which the pace of change seemed to accelerate beyond recognition. I think it was that sense of change happening so fast that one just could not keep up with it, that everything felt unstable. It felt like life was existing on shifting sands. I think it was that feature of the 14th century that really stimulated this kind of nostalgia. We are talking about climate change, in fact. The beginning of the 14th century saw the start of what many historians call the Little Ice Age. The 13th century had been famously warm, and then the temperature dropped by one or two degrees. This can be shown in dendrochronology, ice-core samples and so on. There was then a horrific famine in the 1310s, and in 1348, the bubonic plague strikes.

Saint Roch attending the plague-victims in a lazaretto. © Jacopo Robusti, il Tintoretto, Wellcome Collection

Saint Roch attending the plague-victims in a lazaretto. © Jacopo Robusti, il Tintoretto, Wellcome Collection

We have the Black Death wiping out as much as 50% of the population. That alone — cataclysmic climate change, pandemic and harvest failure — might have been enough to make people quite nostalgic for what had come before. Alongside that, however, we see a series of interlinked changes as well. We see very rapidly shifting socio-economic structures. The differential mortality rates resulting from bubonic plague and harvest failures, in particular, mean that the poor disproportionately suffer, which in turn means those who survive can demand slightly better conditions. This leads to a certain amount of flux in the social hierarchy and certainly a perception of more social mobility.

Political and economic upheaval

It was also a period of huge political change. Political forms changed very dramatically, with rapid dynastic turnover in many areas — regime change in Italy, for example. It was also a period of continued urbanization. That was not a new feature in the 14th century, but it continued to intensify, and certainly contemporaries really felt this sense that towns were growing beyond all recognition. It was a period of huge economic change and massive inflation, provoked in part by debasement of the coinage, and these things snowballed so that prices looked wild to people struggling to survive in that period.

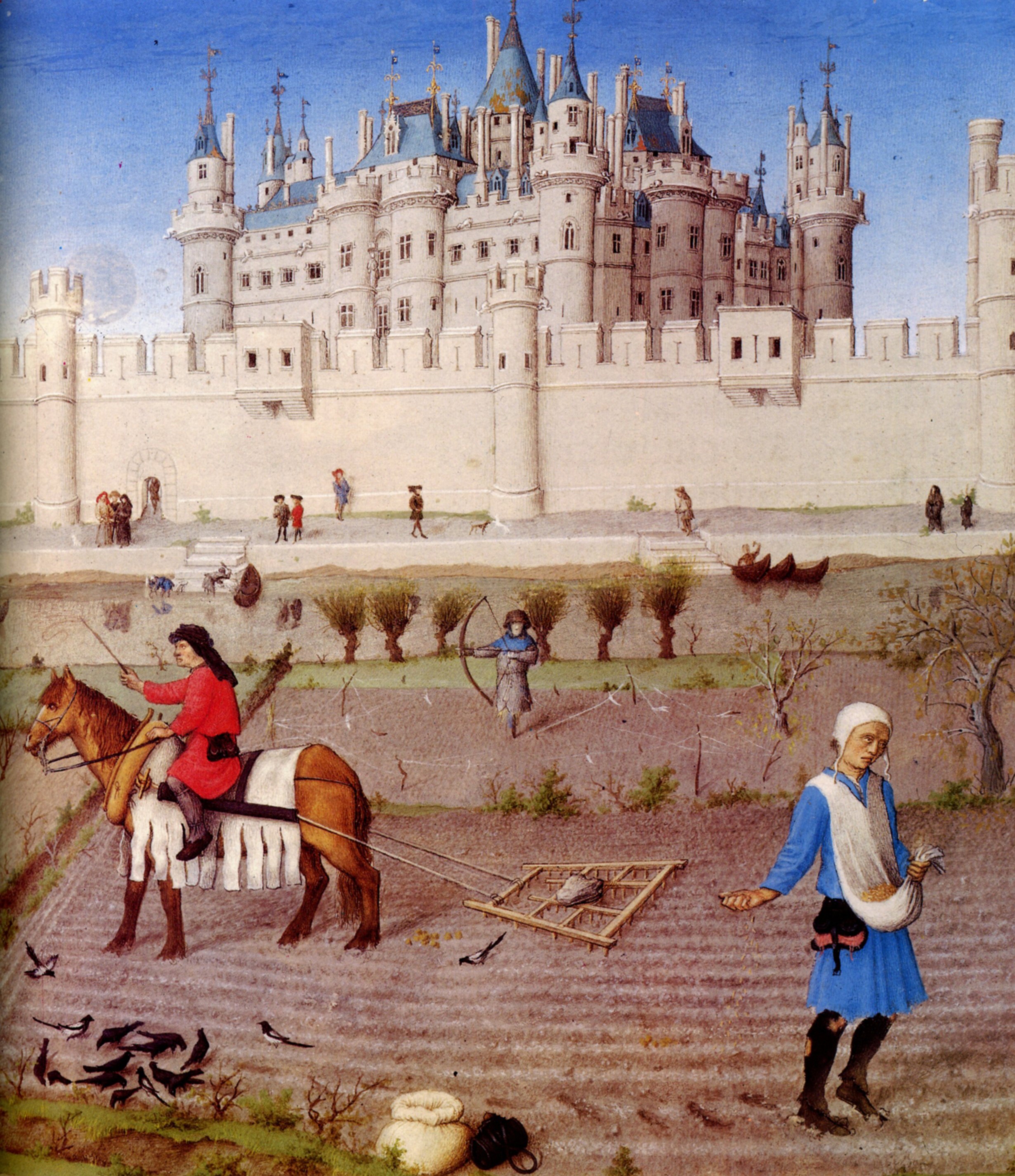

Très riches heures du Duc de Berry © Limbourg brothers / Barthélemy d'Eyck - R.M.N. via Wikimedia

Très riches heures du Duc de Berry © Limbourg brothers / Barthélemy d'Eyck - R.M.N. via Wikimedia

Then, alongside all these huge structural changes, we also find a growth of public discourse generally, a growth of the public sphere. We see a context in which the public is drawn much more explicitly into political discourse, and people across the social spectrum are able to express themselves more loudly than ever, through political petitioning, through poetry and complaint literature, through sermons. There was a sense in which marketplaces in this period became very public arenas for people to speak out. If people were getting nostalgic because change was happening so fast, they were also able to express that nostalgia more loudly than ever.

Nostalgia and rebellion

One of the things that I find particularly interesting about nostalgia is that on the face of it, it is a very reactionary phenomenon. It is about looking to the past and saying things used to be better, and we wish things were not changing so fast. We can see in the world at the moment the ways in which nostalgia can have a very right-wing, reactionary dimension to it. That is certainly true in this period, too. Many react to what seems like huge social mobility with absolute horror, and with a kind of longing for the good old days when people dressed according to their station. They become completely obsessed with clothing, what people wore. We have preachers talking about the good old days when a peasant was dressed in his sackcloth; knights would dress appropriately; the people in between would wear clothing that was appropriate to them, and now it is completely out of control, and so on.

John Gower was a late 14th century English writer. He was also extremely exercised about the subject of clothing, which he saw as epitomizing everything that had been lost in modern society. He wrote, “Now the knave is clothed as was formerly the knight,” then there is an interesting gender dimension when he goes on to write, “and the servant girl as her mistresses.” Interestingly, in an Italian context, these kinds of comments were much more overtly concerned with sexuality: in the past, people dressed much more modestly, whereas in the modern period, as in the late 14th century, people were obsessed with displaying far too much of their sexuality. Nostalgia also has a really radical edge to it; it can be extremely subversive. In this period, we also find nostalgia being used and mobilized by those who were protesting at the ways in which their expectations and their longings for slightly better conditions were being stifled.

The Death of Wat Tyler © Jean Froissart's Chronicles, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The Death of Wat Tyler © Jean Froissart's Chronicles, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The Peasants Revolt in 1381 in England is a fabulous example of nostalgia being mobilized for very radical ends by those involved in the revolt, who look back to a golden age in which people were treated fairly, respected for what they were doing and in which people were given their just deserts for their work. That kind of nostalgia was just as loud and just as powerful in that period.

Nostalgia was a thread running through much of the poetry of Geoffrey Chaucer. For example, he wrote a poem called The Former Age, which draws on classical tropes of a golden age but picks up on contemporary concerns and overlays a 14th-century nostalgia onto that. He wrote of "a blisful lyf, a paisible and a sweete, ledden the peples in the former age. They helde hem payed of fruites that they ete, which the fields gave them by usage."

Chivalric nostalgia

I have been interested in a social nostalgia for a lost social order. I am also interested in chivalric nostalgia, this sense that, in the past, knights were true knights. There is a very interesting gendered dimension to this as well. Petrarch says that "modern knights snort like buffoons," apparently, whereas in the past they behaved like what he calls real men.

The 14th-century preacher Bromyard fulminated against contemporary mores. In one of his tirades, he said, “Who has been heard to praise or could praise any of these modern knights for their strenuous battling with the enemy or their defence of the country or church, as Charlemagne, Roland, Oliver and other knights of antiquity are commended and praised? But rather for this they have a helmet of gold worth £40 and other external insignia of the same style and even greater price.”

King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table © Évrard d'Espinques, Bibliothèque nationale de France

King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table © Évrard d'Espinques, Bibliothèque nationale de France

There is also a sense in which that kind of chivalric nostalgia can be used politically. In England, we find a huge number of references to King Arthur and the Round Table in the 14th century. It is a longing for a period when knights were fully absorbed in the true values of chivalry in a way that has apparently been lost.

The Italian chronicler Villani was highly nostalgic in the 14th century for the 13th and 12th century, which he felt represented a time of great noble values. He wrote, "They were loyal and faithful, they did greater and more virtuous deeds than are performed in our own time.”

Perceiving rapid change

The German sociologist Hartmut Rosa became very interested in the idea of nostalgia and referred to what he called the social acceleration of time, which is a wonderful phrase exploring a sense that we do not experience time all in the same way or in the same way from day to day.

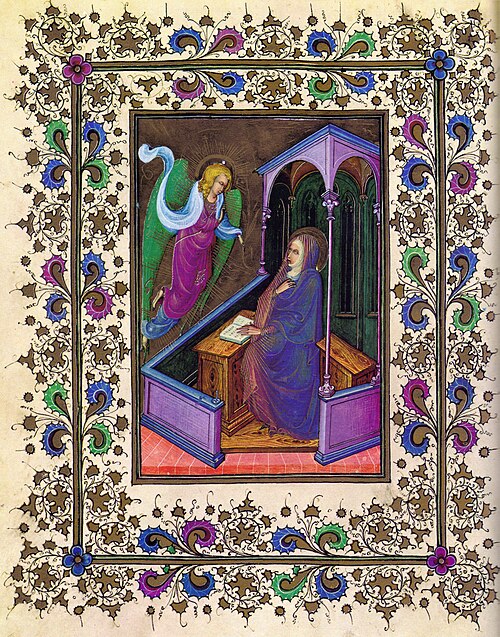

The Visconti hours © Giovannino dei Grassi and/or Belbello da Pavia, National Library, Florence

Sometimes the pace of time seems to pick up; sometimes it slows down. For Hartmut Rosa, part of the experience of modernity, as brought about by industrialization in particular, was what he calls this social acceleration of time — that societies began to experience time faster because change was happening so fast. Things were changing beyond recognition very, very quickly. He says that it was this which stimulated a longing for a stabler, gentler past. I think we can find something very similar in the 14th century. This does not have to be a feature of a post-industrialized Europe. Actually, the changes in the 14th century were happening so rapidly, partly just in the sense of the terrifying levels of mortality. This sense of rapid pace of change was really what stimulated this longing for a gentler, stabler, more predictable past. That in itself has big implications for how we think about medieval versus modern. If we can find this sense of a social acceleration of time in the Middle Ages, as well as in post-18th century Europe, that starts to break down the ways in which we distinguish modernity from other periods of history. It suggests that perhaps we should approach the experiences of medieval people with a little more nuance and subtlety.

Universality of nostalgia

I think nostalgia is really fascinating as an emotion because it is both an individual experience and in that probably pretty universal; some of us have more of a tendency to get nostalgic than others, but I am sure we have all experienced nostalgia of one sort or another.

Faiths Victorie in Romes © The Trustees of the British Museum

Faiths Victorie in Romes © The Trustees of the British Museum

It is also a collective emotion, and it is a collective mode of response to feeling that change is going faster than one can keep up with. In that sense, it is very dependent or very contingent and manifests differently in different periods. I am not myself engaged in a huge comparative study of nostalgia, but I do think that if one thought about this across an even bigger sweep of time, one would find waves of nostalgia at particular moments. Those waves do seem to correspond to moments at which the pace of change picks up very noticeably.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

medieval nostalgia and social change

Skoda, H. (2023). Nostalgia and (Pre-)Modernity. History and Theory, 62(2), 251–271.

Skoda, H. (2024). Pastoral nostalgia in the long fourteenth century. In H. Lyon & A. M. Walsham (Eds.), Nostalgia in the early modern world: Memory, temporality, and emotion (pp. 27–48). Cambridge University Press.

Lyon, H. & Walsham, A.M. (Eds). (2024). Nostalgia in the early modern world: Memory, temporality, and emotion. . Cambridge University Press.

Rosa, H. (2015). Social acceleration, a new theory of modernity. Columbia University Press.

Skoda, H. (2022). Disciplined dissent and nostalgia in late medieval England. In F. Titone (Ed.), Disciplined dissent in Western Europe, 1200–1600: Political action between submission and defiance (pp. 195–221). Brepols.

Skoda, H. (2023). Medievalisms and medieval times: Confronting chronopolitics with medieval textures of time. History and Theory, 62 (4), 142–156.