Women nowadays face quite a problematic contradiction or tension. On the one hand, when you have a baby, you are told you absolutely must breastfeed, breast is best, and there is this huge pressure to breastfeed. On the other hand, we live in a society that is even now pretty prudish and squeamish about seeing people breastfeeding in public. I was interested in whether this tension might be there in the Middle Ages as well and what it felt like for women breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding in the Middle Ages

Associate Professor of Medieval History

- Medieval sources show that motherhood extended beyond biology; wet nurses formed deep emotional bonds with children, and miraculous lactation stories reinforced nursing as a defining act of mothering.

- Medicine and theology agreed that “breast is best,” yet treatises still advised elites on choosing wet nurses, believing a nurse’s moral and physical traits passed through her milk.

- Breastfeeding was a community affair; miracle tales depict relatives, neighbors and clergy rallying around mother-child pairs, countering modern notions of an isolated dyad.

- Figures like Joan of Arc reveal that medieval womanhood was not confined to maternity – contemporaries struggled to fit such non-maternal women into conventional gender categories.

Curiosity about medieval breastfeeding

I became interested in breastfeeding in the Middle Ages partly because I was finding accounts of enslaved women being used as wet nurses, and I wanted to find out more about what was going on there, and partly simply because I had my own two small children when I started this research. I was really curious about the ways in which my experiences may or may not have resonated with those in the past.

Maria Lactans from the Book of Hours of Simon de Varie © KB National Library of the Netherlands via Wikimedia

Medieval motherhood

On the face of it, in the Middle Ages, motherhood is seen in straightforwardly biological terms. Once one starts to dig a little deeper, it very quickly becomes a lot more interesting than that. For example, many parents employ wet nurses to feed their children, and there is a lot of evidence that extremely affective emotional relationships developed between wet nurses and the children. We have a number of wills where people leave money to their wet nurses. The story of Saint Kellum is rather lovely. He is part of the Saints story. He is assassinated, and as he is dying, he says to his wet nurse, "Oh, my sweet mother!" and she responds, sobbing, "Oh, my dearest son." There is quite a strong sense that motherhood involves something slightly more than being the person who gave birth to somebody.

There are also gorgeous stories of breastfeeding itself producing a sense of motherhood. There is a wonderful miracle story from the collection of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino about an elderly couple who were Franciscan tertiaries. They find an abandoned baby, discover it is emaciated and covered in sores, and they are desperate to look after this tiny, tiny baby.

St Nicholas of Tolentino © Franciabigio, Ashmolean Museum Oxford via Wikimedia

St Nicholas of Tolentino © Franciabigio, Ashmolean Museum Oxford via Wikimedia

They pray to Saint Nicholas of Tolentino to help them, and this very old woman suddenly finds that she is beginning to lactate, and she is able to feed this baby. She and her husband, an old man, become the parents of this child. They are not biological parents; they become parents by virtue of the saint's actions and by virtue of her being endowed with this miraculous milk.

The Virgin Mary as a model

Motherhood in this period is also modeled on the motherhood of the Virgin Mary in many ways. The Virgin Mary represents a very particular kind of mother – in many ways a rather problematic one. She is so perfect, so pain-free in the ways in which she gives birth to Christ and so altogether wonderful that she can be demoralizing rather than empowering for contemporary women. However, the Virgin takes on an increasingly feisty personality in later medieval representations.

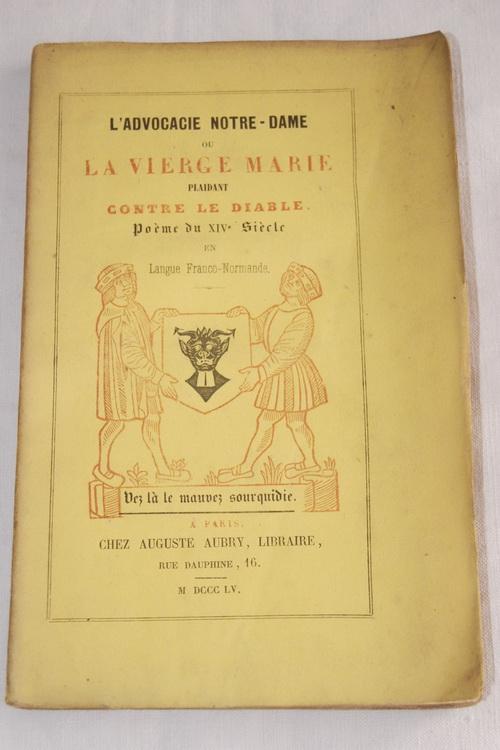

L'Advocacie Notre Dame © Bibliothèque nationale de France via Wikimedia

There are some wonderful accounts of Mary transposed into a fictionalized court of heaven, defending humankind against the devil, who has come to claim his due. In one of these stories, called L'Advocacie Nostre Dame (“The Advocacy of Our Lady”), she is standing there in the court of heaven, and she argues the case for humanity in front of God, the judge, and she is not winning. In the end, in a fit of impatience, she rips open her dress and bares her breasts at God, who is sitting enthroned in this court, and says, “You are my son, and I am your mother, and these are the breasts which I fed you with, so you will do as I say.” At which point God says, “Yes, mother,” and she gets her own way. We have these extraordinary stories of a Mary who is anything but submissive and obedient and who mobilizes the fact that she breastfed God in order to get him to do what she wants. She is a very interesting model for women in this period.

Intensity of maternal ties

Madonna lactans © Lippo Memmi, Gemäldegalerie via Wikimedia

If we look at Lippo Memmi’s image of the Virgin Mary breastfeeding the baby Jesus, we can see her looking down at him with a very gentle, loving look on her face. We can see Jesus gazing outwards toward the viewer, reminding them that he is a baby, but he is also the Godhead. One comes away, nevertheless, with a very strong sense of the emotion and affection involved in breastfeeding, and that certainly seems to have carried over into "real-life" experiences of breastfeeding.

I have been looking at miracle collections as a really wonderful set of sources and insights into what it felt like for real mothers breastfeeding their babies. Again and again in these collections, we get a sense of the sheer love and emotion involved in these relationships. I think quite often people are tempted to assume that in the past people perhaps did not have quite as intense ties with their children. Sometimes, people are even tempted to assume that, because infant mortality was so high, people did not allow themselves to experience close ties with their children. Of course, that is a rather horrible way of thinking about things, but it is also very clearly untrue. We repeatedly find stories of mothers absolutely devoted to their children, that devotion being manifested in these episodes of breastfeeding.

Medical views on breastfeeding

Fundamentally, in this period they believed, as many do now, that breast is best. There was a very strong sense among medical practitioners, among theologians, that the best thing for a child was to be breastfed by its mother. We find a huge number of preachers, theologians and physicians telling mothers that they should breastfeed their own children, emphatically, that they should not use wet nurses.

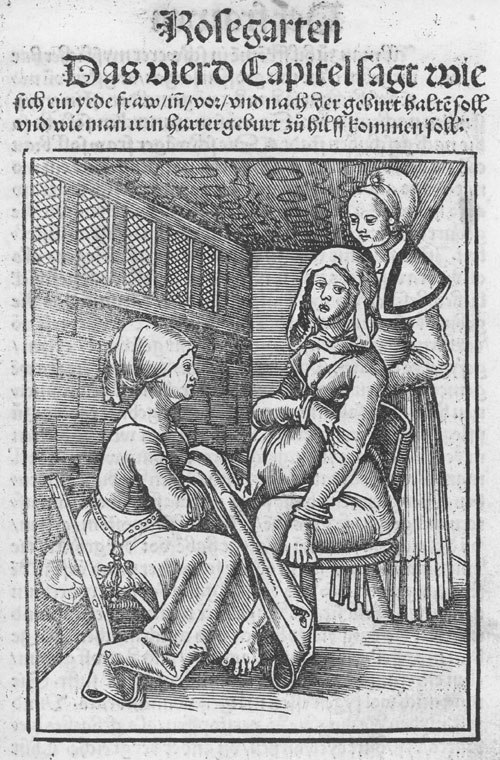

A woman giving birth on a birth chair. © Eucharius Rößlin via Wikimedia

It is very striking that in many of these treatises, women are emphatically enjoined to breast-feed their own children and told that using a wet nurse is a terrible thing to do; you should feed your own child. Not to do so is an expression of vanity, that women are just doing it because they want to continue to look amazing. Yet, these treatises then go on to say that if you must use a wet nurse, this is how you should select somebody. Aldebrandin of Sienna is an interesting author of a treatise precisely about this sort of thing. They give advice about choosing wet nurses because of a belief that certain characteristics of the mother, or of the person who is feeding the child, might pass on to the child through the breast milk. For that reason, they are very emphatic, not just that you need to pick a wet nurse who seems strong and whose own children seem strong (because that indicates that the milk is very nourishing and so on), but you also want to pick a wet nurse of good character, who looks the way you want them to look and who holds the kinds of values you want them to hold.

Other things that were taught were actually surprisingly resonant with current medical thinking nowadays. For example, the World Health Organization now tells women that they should breast-feed up to the age of two. We generally get told up to the age of one, but the official guidance is up to the age of two, and that is exactly what they were doing in the Middle Ages, too.

Social status and nursing

To some extent, breast-feeding practices in this period were shaped by social status. Obviously, those of more elite status with more economic means were able to employ wet nurses to feed their children. I think we really should not see this just as a phenomenon for those at the top end of the social scale. The very basic point is the maternal mortality was so high in this period, so many mothers died in childbirth, that wet nurses, or at least other women who were prepared to share their milk, were needed right across the social spectrum. It is just as likely, in many ways, that a peasant infant might be fed by somebody who was not his own mother. We have many, many examples of milk sharing in particular – other women involved in feeding an infant but who are not being paid for it – happening right across the social spectrum.

Sources for lived experience

In thinking about medieval breast-feeding, I really wanted to get a sense of what it felt like for the women involved. Wonderfully, there are sources which enable us to do this, to hear the voices and think about the experiences of women, again, across the social spectrum. One of the most productive kinds of sources to work with in this respect are miracle collections. These are collections of miracles apparently enacted by saints in the Middle Ages. This becomes an incredibly popular phenomenon from the 12th century; I think Rachel Koopmans has spoken of a "miracle-collecting mania".

Canterbury Cathedral © Wikimedia

Canterbury Cathedral © Wikimedia

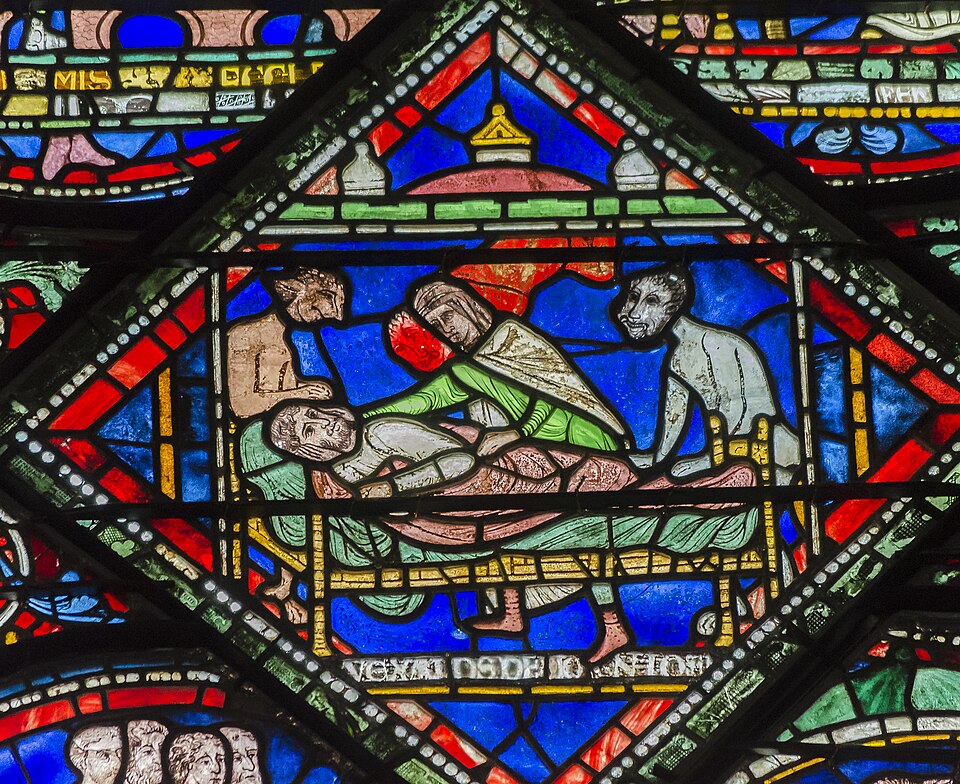

We have many of these collections, and they tell of people from peasants to noblewomen who seek out saints, or the remains of saints, in order to work miracles. In many cases, nothing to do with children – to cure illnesses or to bring about some betterment in people’s circumstances – but there are many, many miracles which do involve children and many which do involve infants.

Infant mortality is obviously so high in this period that many people desperately pray to saints for anything they might do to help them in their hour of need, and sometimes this then resulted in a wonderful story which would be noted down. From the later 13th and into the 14th centuries, the process of becoming a saint became more institutionalized, and at that stage people would conduct full-on investigations into the miracles which had been accomplished by a particular saint. These kinds of investigations give us detailed accounts of the women who would come to these shrines seeking a cure for their children.

Parental distress in miracle tales

One of my favorite stories – and I like this one because I come from North Wales – is about a little boy named Roger, who was about two, who was the son of the cook in Conway Castle in North Wales. His mother and father had both put their children to bed, and then they had gone off to a funeral service. Anyway, this little toddler manages to climb out of his cradle, goes to try to find his father in the castle and falls into the moat in the middle of the night. When his parents realize this, they are absolutely distraught. The story gives us a sense of just how distressed and distraught they are. They send prayers and offerings to the shrine of Thomas Canteloupe, who was Bishop of Hereford, who had died and who was believed to have these kinds of miraculous powers. The little child is brought back to life, apparently, and he is then picked up by his mother, put inside her cloak to warm him next to her skin and then suckled by her. The breast-feeding in that story is the moment of reunification of mother and child.

The Miracle of the Newborn Child © Titian, Scuola del Santo

The Miracle of the Newborn Child © Titian, Scuola del Santo

What is really interesting about this story is that the father is present; there is a stranger present who spotted the body in the moat; all the townspeople are present in concentric circles. There is a whole community involved in bringing this child back from the cusp of death.

Community in child-rearing

I think the most important aspect that I have discovered in thinking about breast-feeding in the later Middle Ages is the role of the whole community in these episodes. Nowadays, we are really encouraged to think about breast-feeding as a kind of mother-child dyad. It is this very intimate moment between mother and child. Even if one thinks about the promotional material produced to encourage people to breast-feed, or even the material produced by companies producing formula milk, it always tends to be a parent figure, usually a mother, and the child. In the Middle Ages, that really does not seem to be the case. Again and again in these stories, there is a sense of the involvement of the wider community.

Naissance de Philippe Auguste © Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève via Wikimedia

That is partly because miracle stories are about a wider community, but it is also because people were thinking about these things in a wider sense – that there is a huge group of people involved in bringing up a child. There is one very interesting miracle story where a mother sounds probably as though she is suffering from postpartum depression, though I am a little skeptical about our ability to post-diagnose these accounts. Anyway, she is very miserable; she is unable to feed her child; and she is really desperate. In the story, we are told about how the priest’s wife – interesting phenomenon in itself – comes, places the child on her breast, shows her how to do it and the child starts suckling. Around this trio of the mother, the priest’s wife and the baby, we have the father, various siblings, an aunt, a grandmother and then a wider community, too. So there is a sense that many, many more people are involved in these kinds of episodes. It is a relationship which is wider and more expansive.

Joan of Arc beyond maternity

Joan of Arc is a really fascinating figure in this period, partly simply because of what she achieved. I think we should never lose sight of the sheer extraordinariness of the fact that a woman, who was still a teenager of a peasant background, was able effectively to insert herself right at the center of court life, to lead an army, to lead a military campaign which enjoyed such outstanding success.

Jeanne d'Arc © Archives nationales

Jeanne d'Arc © Archives nationales

Joan was such an interesting figure equally because she does not fit into any of the straightforward categories that we might have for thinking about men or women in this period. Joan was, of course, never a mother herself. She played a great deal on the fact that she was a virgin. She could describe herself as the Pucelle, as the maid, and she presented herself as a military commander; she very emphatically chose to dress a particular way.

Joan and labels

Joan is also so interesting because so many people were busy writing about her as well and saying things about her. One of the most interesting texts on Joan is a poem by Christine de Pisan, who is a fascinating, rather inspiring late 14th- or early 15th-century writer, specifically about women. Christine was fascinated by the fact that a woman could have achieved everything that Joan achieved; however, she reframes Joan as a mother of France, as a nurturing figure who has brought France back from the brink. Joan sees herself as many things but not really as a nurturer in that sense. So, there is a sense of shoehorning her into something that Christine wants her to be.

Of course, those who are opposed to Joan equally shoehorn her into all kinds of other categories that she does not really fit into. That sense that we have a whole series of texts desperate to categorize and to make her into something, but that actually, as historians, we can get the most purchase by listening to Joan herself and listening to the ways in which she refuses all these labels, is really rather inspiring.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

breastfeeding in the Middle Ages

Skoda, H. (2024). Women and popular beliefs. in Women in Christianity in the Medieval Age. Taylor and Francis.

Skoda, H. (2024, January 18). An act of love: Breastfeeding in the medieval period. BBC History Magazine.

Skoda, H. (2012). La Vierge et la Vieille: L’expertise féminine au XIVᵉ siècle. In Société des historiens médiévistes de l’Enseignement supérieur public (Ed.), Experts et expertises au Moyen Âge: Consilium quaeritur a perito (pp. 299–311). Éditions de la Sorbonne.

Koopmans, R. (2010). Wonderful to Relate, Miracle Stories and Miracle Collecting in High Medieval England.. University of Pennsylvania Press.