It is a really interesting part of the ancient world in particular, because it was a crossroads of cultures and civilizations. It is located at the point where overland routes coming down north through Anatolia, but also through the Caucasus, will meet the overland routes coming up through Mesopotamia and from the Near East. That is where they also join with the sea routes, which connect the Mediterranean as well. Throughout history, Cilicia has been very much a melting pot. In the medieval period, we know that this was the location of Arab groups, Armenian groups, as well as Greek groups — Byzantine Greeks as well.

Cultural identities in Ancient Greece

Professor of Greek Archeology

- The case of Cilicia really helps us to understand that identities can change, and they can change quite rapidly in response to specific historical contexts.

- Cilicia sat at a strategic crossroads linking Anatolia, the Near East and Mediterranean sea routes, which made it a long-standing melting pot of peoples and traditions.

- Archaeology shows mixed assemblages and blended crafts, with Aegean Greek, Anatolian, Phoenician and Persian elements coexisting and intertwining.

- As Persian rule intensified, some cities adopted Greek language, coinage, art and civic practices as a self-driven stance against imperial power.

Cilicia at a crossroads

Cilicia lies in the south of the Anatolian peninsula. If you go immediately north from Cyprus, the first bit of land that you hit in Anatolia is Cilicia.

Cilicia and the surrounding regions in the Iron Age

Cilicia and the surrounding regions in the Iron Age

Cilicia is the point of the Anatolian peninsula where you drop down from the highlands of the Anatolian plateau into the lowlands that border the Mediterranean Sea.

A cultural melting pot

Uniquely within the ancient Greek world, Cilicia really is a melting pot of different peoples. It is perhaps the edges of a settled Greek area, but it is also very much on the fringes of the Near Eastern world, too. We know that we have large communities of Phoenician speakers who live here; we know that we have communities of people who are speaking the indigenous Anatolian language of Luwian; we know that this area gets incorporated relatively early into the Neo-Assyrian, the Neo-Babylonian and then the Achaemenid Persian empires. So, we really have this layering of different types of ethnic and linguistic groups coexisting together throughout antiquity. For me, this is part of why Cilicia is so exciting.

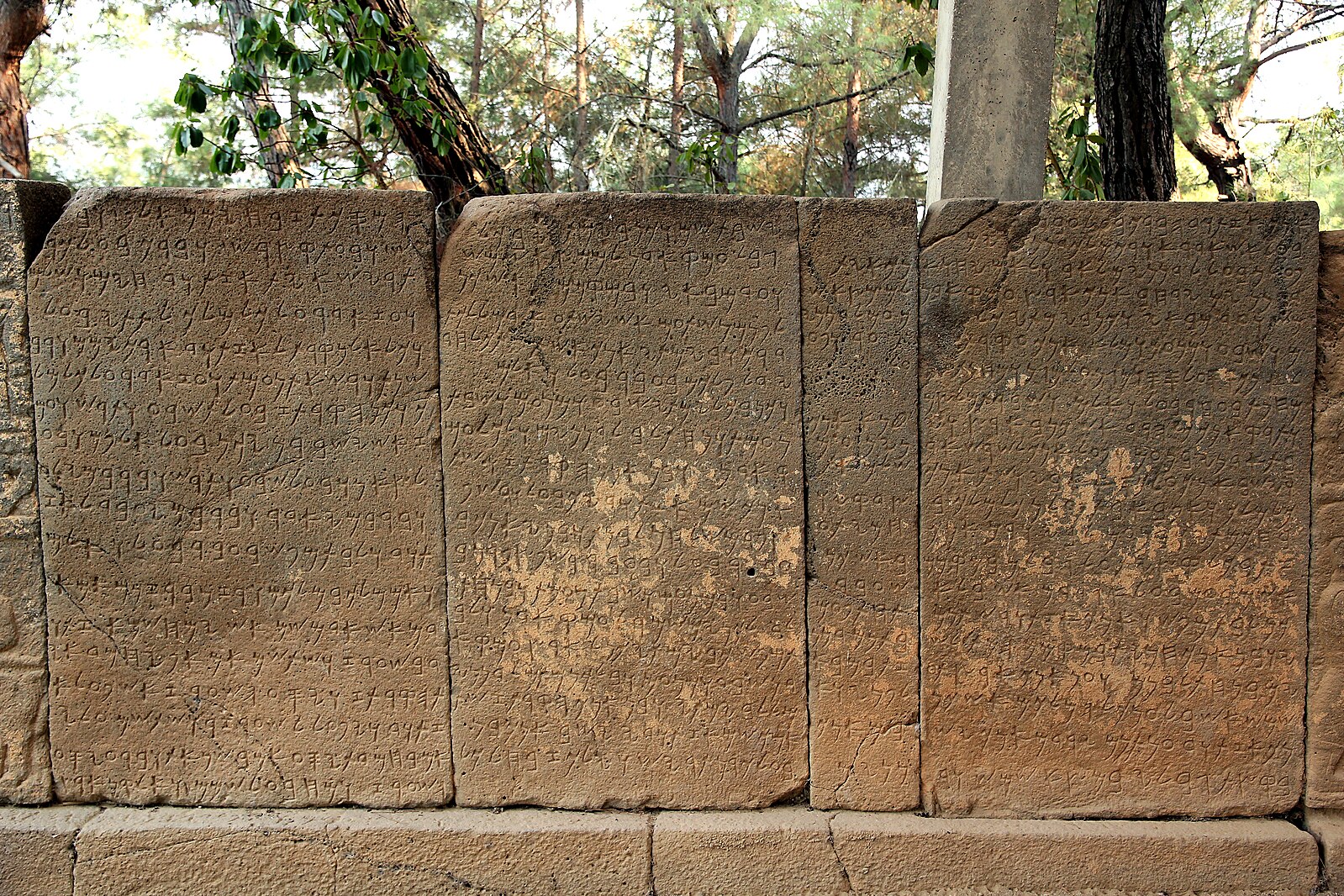

The Karatepe bilingual inscription (8th century BC) © Klaus-Peter Simon via Wikimedia

The Karatepe bilingual inscription (8th century BC) © Klaus-Peter Simon via Wikimedia

Cilicia is really a region where we can see a fantastic patchwork of different cultural traditions: Greek traditions, certainly, but also Anatolian vernacular traditions, Persian traditions, Near Eastern traditions, Cypriot traditions and Phoenician traditions.

In terms of trying to understand Greekness in antiquity, Cilicia really helps us to push at the boundaries of what was considered Greek, what was considered not Greek, how Greekness could coexist alongside and be interconnected with other types of identities and other kinds of cultural traits.

Parallel traditions

Excavations at Kilise Tepe, Cilicia, © Bob Miller

Excavations at Kilise Tepe, Cilicia, © Bob Miller

Archaeological research in Cilicia is particularly exciting because of this cultural diversity. When you are excavating, you can find artifacts which are typically Aegean Greek in style and manufacture, but these will be coexisting in the same assemblages as artifacts which have been imported from the Persian Empire or artifacts having come from an indigenous Anatolian tradition.

One of the things we can see in Cilicia, for example, is parallel traditions growing up alongside and developing alongside each other.

The local ceramic traditions draw very heavily from Aegean Greek styles and techniques, but they also draw from a long tradition of Anatolian ceramics as well. We can see different elements in the manufacture of these local ceramics intertwining and being used alongside each other in Cilicia.

Greek and Persian influences on politics

In Cilicia, in the Iron Age, moving into the Archaic period, between about the 9th and the 6th centuries BCE, we find a long period of local interactions and complex connections, where different groups appear to be living very much alongside each other. We have excellent evidence for multilingualism. We have the same communities using Phoenician language and script but also using an Anatolian language and script called Luwian. In these communities we have evidence for Greek speakers engaging as well.

Archers frieze from Darius' palace at Susa © Louvre Museum

Archers frieze from Darius' palace at Susa © Louvre Museum

For a period of several centuries, there seemed to be several different local kings who were operating within the region. They are intermarrying with each other; they are fighting with each other. They are drawing from various different cultural traditions from around the Near East and the Mediterranean. Into this comes the Persian Empire in the 6th century.

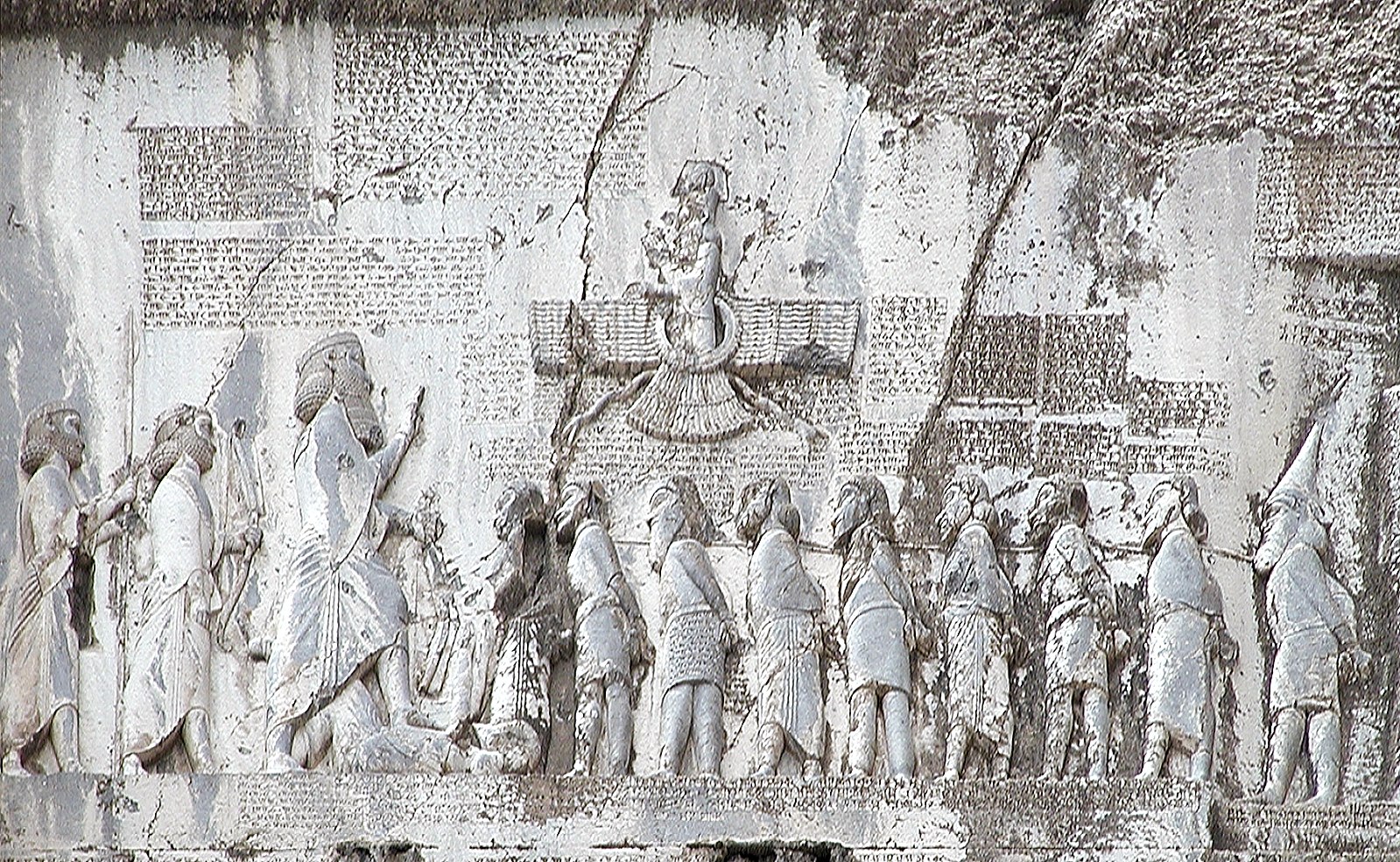

Persian imperialism

The Persians conquer Cilicia in the middle of the 6th century. The impact of Persian imperialism is initially fairly light. Things carry on more or less the same as they have done for generations before, and we continue to find a patchwork of different groups operating within the region. Over the course of time, however, Persian imperialism begins to weigh more and more heavily on the people of Cilicia, and we start to see a polarization in terms of the cultural orientation of different communities.

Darius I of Persia, rock relief, Behistun © Hara1603 via Wikimedia

Darius I of Persia, rock relief, Behistun © Hara1603 via Wikimedia

There are some communities which align themselves more and more closely with the Persian occupiers, and there are some communities which seem to try and be the polar opposite of the Persians.

Self Hellenization

At this time, some of these Cilician communities start to adopt more and more Greek cultural features. They start to mint coins on a Greek weight standard, featuring Greek iconography and using Greek legends and script on them.

Stater of the Satrap Mazaios with a lion, Cilicia, 340 BC. © cgb.fr via Wikimedia

Stater of the Satrap Mazaios with a lion, Cilicia, 340 BC. © cgb.fr via Wikimedia

They start to import more pottery and ceramics from the Greek Aegean, and they start to emulate more Greek styles when it comes to aesthetic preferences and the monumental arts and sculpture.

We also start to find increasing evidence for the use of the Greek language, in particular when it comes to civic life and public life. Taken all together, what we seem to have is evidence in the second half of the 5th century for a process of self Hellenization by some of the cities of Cilicia. Now, this is very internally driven. It is something that local communities are seeking themselves, and it is really driven by this local play of power, trying to articulate a cultural identity that is distinct from that of the Persian imperial authorities. However, while this is very internally driven, it is also partly a response to what is going on in the wider Mediterranean world at the time.

Greekness as a political stance

At the start of the 5th century, we have had a series of open conflicts between a coalition of Greek city states in the Aegean and the Persian Empire. This has led to ongoing tensions and campaigns around the eastern Mediterranean by that Greek coalition, which has fought naval battles off the coast of Cyprus and Egypt.

Persian Warrior (Left) and Greek Warrior (Right) in a Duel © National Museums Scotland

Persian Warrior (Left) and Greek Warrior (Right) in a Duel © National Museums Scotland

Around this time, there is a developing rhetoric of Greekness as an opposition to Persianness, Greeks being the freedom fighters or the resistance against Persian imperialism, especially against its spread in western Anatolia and into continental Europe. For the Cilician cities, Greekness then has a powerful political force. Greekness may not have been something that they necessarily felt. They did not necessarily feel a deep-seated sense of Greek identity and roots, but Greekness is almost a political stance. It is something that they can embrace as a way of expressing their opposition to Persian imperialism.

Identity as a political tool

What we seem to see in Cilicia is a spiraling of harsher and harsher Persian rule, with more and more expressions of Greek identity. One seems to counteract the other. We have the first explicit engagements with Greek civic identity in the middle of the 5th century, on the part of the Cilician cities.

Almost in response to that, the Persian Empire rethinks the way it administers the Cilician region, and it replaces the local system of governance with a top down Persian governor. Then we have an increasing engagement with Greek cultural identity, Greek religion, Greek language, Greek customs on the part of the Cilician cities, and then on top of that, the Persians impose a much more military regime. They create a number of garrisoned fortresses around Cilicia through which they can control the local population in a much more direct and oppressive way. Then again, in response, that is when we see a real flowering of Greekness in terms of Greek styles of culture, Greek aesthetic styles and Greek art.

Chronologically, we can really trace heightened engagement with Greek culture on the part of the Cilician cities with increasing Persian oppression from the imperial authorities, and the two seem to be in direct counterpoint to each other.

Resistance and revolt

We know that this resulted in a series of different revolts and rebellions. Some of these were armed; some were more political in nature. These included support for the rebellion of a Persian pretender to the throne, Cyrus the Younger, in the early 4th century. It also resulted in support for the breakaway activities of the Cypriot king Evagoras the First.

Alexander and Bucephalus - Battle of Issus mosaic © National Archaeological Museum, Naples

Alexander and Bucephalus - Battle of Issus mosaic © National Archaeological Museum, Naples

The end of all of this process comes about with the conquest of Alexander of Macedon at the end of the 4th century, when Alexander conquers the Persian Empire and transforms it into a kind of Perso-Greek Macedonian empire. All of these debates become reimagined in this Hellenistic Greek world.

From that point onwards, after the conquests of Alexander of Macedon, the Greekness of the Cilician cities ceases to have any real political meaning. The Cilician cities just become part of this wider Hellenistic world, one which is a fundamentally hybridized world which incorporates Greek and Near Eastern elements. For the Cilician cities, of course, this is nothing new.

Culture always political

What I think the case of ancient Cilicia can tell us is that cultural identities are always political. We feel certain elements of cultural identity more or less strongly in relation to the political environment that we are in. Whether it is consciously or unconsciously, that varies, but culture is always political.

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

If there is one misconception this should help us address, it is the misconception that identity is always necessarily primordial and underlying, and that it has always been there. The case of Cilicia really helps us to understand that identities can change, and they can change quite rapidly in response to specific historical contexts.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

cultural identities in ancient Greece

Mac Sweeney, N. (2021). Race and Ethnicity. In D. McCoskey (Ed.), A Cultural History of Race. Volume I: Antiquity (pp. 103-118). Bloomsbury.

Mac Sweeney, N. (2011). Separating fact from fiction in the Ionian migration. Hesperia, 86(3), 379–421.

Mac Sweeney, N. (2021). Regional identities in the Greek world: Myth and koinon in Ionia. Historia, 70(3), 268–314.