The dominant explanation for why we have seen 80 years of “nuclear peace” is deterrence: the notion that states are deterred from using their nuclear weapons by the expectation that other states could then use nuclear weapons against them. Deterrence is the dominant explanation for why we haven't seen the use of a nuclear weapon in armed conflict since 1945. There is also an alternative explanation or a factor that some scholars argue we should also take into account, which is the idea of a nuclear taboo: the notion that there is a strong moral prohibition on using nuclear weapons, specifically, a prohibition not of using them in particular ways, but simply a prohibition on resorting to nuclear weapons.

Nuclear deterrence and taboo?

Professor of Global Security

- Deterrence is the dominant explanation for why we haven't seen the use of a nuclear weapon in armed conflict since 1945. An additional factor that some scholars argue we should take into account is the idea of a nuclear taboo.

- Surveys show different publics prefer conventional force but will support nuclear use if it promises better outcomes. That is not the structure of public opinion that we would expect if there was a nuclear taboo.

- Countervalue targeting – the use of nuclear weapons against civilian populations – is illegal under international law, and even counterforce plans face serious necessity and proportionality issues; by today’s standards Hiroshima and Nagasaki would be unlawful.

- Deterrence alone is not enough to minimize the risk of nuclear escalation. A multi-pronged approach of public education, stronger safeguards and measured deterrence is required, since the biggest risk for nuclear use is either escalation from an ongoing armed conflict or a mistake.

The “nuclear peace”

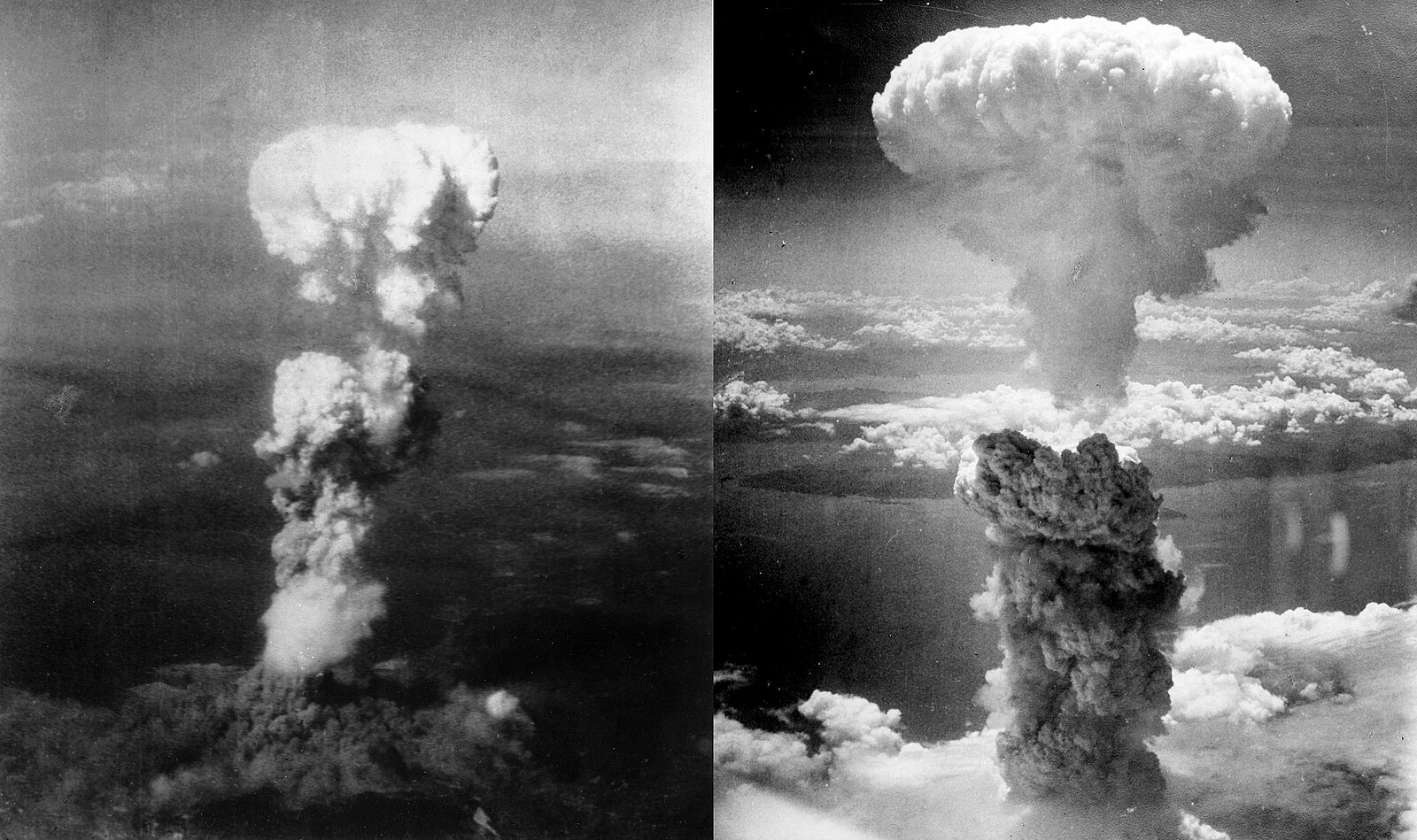

Nuclear weapons were created about 80 years ago, and they were used almost immediately after their creation, in August 1945: twice against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the United States in the closing days of World War II. Eighty years later, we want to explain why that is still the only time that nuclear weapons have been used in armed conflict. We now have nine states in the international system that possess nuclear weapons that they could use in armed conflict, and they haven't.

The Memorial Cenotaph at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park © Balon Greyjoy via Wikimedia

A categorical prohibition?

A taboo is a particular kind of moral prohibition, one that we can best think of as categorical. It is a prohibition that is not sensitive to the expected consequences of doing or not doing something. Many prohibitions, for instance on using violence, can be overridden if we expect particularly good consequences, so if using violence is the lesser evil. A taboo or a categorical prohibition cannot be overridden. Certain types of acts are in a category so evil that we never contemplate undertaking them, even if they would have good consequences, or even if not undertaking them has really bad consequences. A categorical prohibition is a prohibition where a lesser evil justification is not available. There are very few taboos that are widely shared. The two examples people often give of taboos are incest and cannibalism. These are acts that we tend not to contemplate even if we thought we would get away with them – even if not engaging in these acts might have bad consequences. One explanation for the non-use of nuclear weapons is that there is a taboo against using them.

Atomic bombing of Japan © George R. Caron & Charles Levy via Wikimedia

The political scientist who has most prominently argued this is a professor called Nina Tannenwald, who wrote a book in 2007 called The Nuclear Taboo. She looks particularly at the United States, which, as the first state to have nuclear weapons and the state with one of the biggest arsenals of nuclear weapons, at various junctures in its history might have used nuclear weapons. Tannenwald argues that we can't fully explain the United States consistently opting against nuclear weapons use without this idea of a taboo.

Public opinion on nuclear use

In principle, a nuclear taboo could be something that only elite political decision makers subscribe to. They believe that it is categorically wrong to use nuclear weapons, but the societies around them don't necessarily believe that. That would be quite surprising, because taboos are such strong prohibitions that for a person to buy into them without the society around them believing something to be wrong is unlikely. Often taboos involve emotional disgust. It would be surprising if only the American politicians who make decisions about nuclear use had that reaction to nuclear use.

One way in which we could test the theory of a nuclear taboo is therefore to look at public opinion. My co-authors started this work by asking, is there a nuclear taboo in the US public? Does the US public believe that it is categorically wrong to use nuclear weapons in all circumstances, regardless of the consequences, and may the heavens fall?

© TimMilesWright via Wikimedia

My colleagues Scott Sagan and Ben Valentino, who started this research program, did not find this to be the case. I paired up with them to look at this more systematically and across different countries, and wherever we looked, we did not really find this taboo. If publics believed in a nuclear taboo, we could not tempt them with good consequences. We found that most people in most countries we looked at don't like nuclear weapons. They prefer to use conventional weapons. If you give them a hypothetical scenario in which they face a very significant threat, and they have two options, large majorities will say, let's use the conventional weapon. However, if you then tempt them with better consequences, with nuclear weapons being more effective, majorities, particularly in the United States, France and Israel, are rather ready to endorse the use of nuclear weapons by their leaders. That is not the structure of public opinion that we would expect if there was a nuclear taboo.

Nuclear weapons in compliance with law?

International law outlaws some weapons with specific treaties. There is a treaty that prohibits the use of nuclear weapons, which was adopted in 2017. Unfortunately, none of the states that possess nuclear weapons have ratified the treaty. So they are not bound by it.

UN working group on nuclear disarmament © ICAN-Australia via Wikimedia

Since we do not have a prohibition specifically of nuclear weapons, the question is whether you can use nuclear weapons in compliance with the principles that must be obeyed in all attacks: the principles of distinction, necessity and proportionality. That is contested. There are those who argue that it is possible to come up with a scenario of a nuclear attack that complies with these principles, whereas others argue that in most scenarios in which states would likely use a nuclear weapon the attack would violate the principles of distinction, necessity and proportionality.

Nuclear target plans

We do not know very much about how states plan to use nuclear weapons. Nuclear plans are, by and large, classified. We know most about nuclear plans in the United States because of a consistent effort to research that, for reasons of declassification, and because the United States communicates much more about its nuclear posture than most other nuclear armed states.

Exercise Desert Rock I © Federal Government of the United States via Wikimedia

During the Cold War, the United States consistently practiced two types of nuclear targeting that are sometimes called “countervalue” and “counterforce” targeting. Countervalue targeting is mostly understood as the use of nuclear weapons against cities, against civilian populations. It was considered to have a high deterrence value: If the Soviet Union or China expected their major cities to be subject to a nuclear attack, that would be effective in deterring them from using nuclear weapons in the first place. Countervalue targeting is categorically incompatible with international law, because it basically means directing a nuclear weapon against a civilian population, which the principle of distinction outlaws. What we find – this can be tracked with material that is available open-source – is that the United States gradually moved away from countervalue targeting in its operational planning as it also gradually moved towards embracing the applicability of international humanitarian law to nuclear targeting. These are parallel processes, and they culminate in a presidential-level declaration by President Obama in 2013, in which the United States declared all operational plans for nuclear weapons to be fully compliant with the laws of armed conflict. Similarly, the United States also now has a “counterforce-only” posture. It no longer directly targets enemy cities with nuclear weapons.

International Humanitarian Law and nuclear use

For some people, that ends the discussion: since the United States no longer engages in countervalue targeting, nuclear plans are unproblematically compliant with international humanitarian law. However, that is not the case, because there are also the principles of necessity and proportionality to consider. The principle of necessity, for instance, implies that when it is possible to destroy a particular target in ways that create less civilian harm, then this is obligatory. Whenever a particular nuclear target could in principle be neutralized with a conventional weapon, on the assumption that conventional weapons cause less civilian harm, particularly through radiation and fallout, then a conventional weapon would have to be used.

Ballistic missile warheads © BalkansCat via Shutterstock

The question that looms particularly large concerns proportionality: given what we know about the civilian harm that nuclear weapons cause – hundreds of thousands of casualties would be expected from most kinds of standard nuclear attack scenarios – how can that ever be proportionate? What is the military advantage that could render such reasonably expected civilian harm proportionate? Even in counterforce targeting, very significant questions remain unanswered about whether and how nuclear use can be permissible under international humanitarian law.

Legality of the atomic bombings today

If we held the attacks of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to the legal standards that prevail today, they would not be compliant with international law. Interestingly, when President Truman justified the first attack publicly, he spoke of a military base as the target, but it is quite clear that the weapon was aimed at the center of Hiroshima. These attacks would violate the principle of distinction as we see it today. Principles of necessity and proportionality are harder to judge, but basically, these attacks would not be compliant with international law as we understand it today.

Legality of threatening nuclear use

A threat to resort to a war that would be illegal if carried out is an illegal threat in international law. It is slightly less clear whether a threat to use a nuclear weapon in a war that could be legal overall, for instance because it is a war of self-defense, is illegal if the nuclear attack would violate international humanitarian law. Whether an articulation of a nuclear plan for the purpose of deterrence is illegal as a threat, if that attack plan if carried out would violate international humanitarian law, is, to some extent, contestable.

Reducing nuclear risk: beyond deterrence

I think the most important question for us is: what is the best package of means that we should rely on to prevent nuclear war? What raises the nuclear threshold the most? What I learned from my research into the nuclear taboo is that we can't take comfort from the notion that the public in democratic states would be constraints on a hawkish leader that is tempted to use nuclear weapons. We know that, particularly in democracies, but even in autocracies, public opinion or perceived public opinion can influence how political leaders make important decisions about the use of force. If we thought that there was a strong nuclear taboo, we might take comfort in the assumption that the threshold for political leaders to resort to nuclear weapons is high, because they do not want to incur the wrath of a population that has internalized a nuclear taboo. The findings of our research suggest that there is a dislike of nuclear weapons but not a categorical prohibition. We cannot rely on the public alone then. Neither do I think we should only rely on deterrence. Deterrence is really important, but it also has costly consequences. To shore up deterrence, nuclear states are consistently tempted to invest in more nuclear weapons and to adopt ever more aggressive and forward-leaning postures, which raises the risk of an accident or unwanted escalation. Both deterrence and moral arguments about nuclear weapons are important, but neither is alone sufficient to prevent nuclear use. We need a large concerted effort to delegitimize nuclear weapons, to educate the public about the consequences of nuclear weapons and to renew efforts to institutionalize non-use of nuclear weapons.

© United Nations

Unfortunately, in the current geopolitical climate, there seems to be limited appetite for that. By and large, European states have reacted to nuclear saber-rattling by Russia with the correct realization that they need to invest in defense and that they need to shore up deterrence, but I think that can't be the only leg we stand on in the effort to prevent nuclear use.

Limits of relying on public opinion

I have studied attitudes towards the use of force across different countries, in Western countries but also in conflict-affected countries like in Ukraine, Iraq and Afghanistan. The one lesson I take away from that is that it is a mistake to think of public opinion as some kind of repository for moral truth or guidance. Often, people embrace views that are quite problematic; many people are not particularly well informed. They can't be, because not everybody can spend all their time thinking about the politics or morality of war. At the same time, it is equally a mistake to ignore public opinion or to not try to figure out what people think, because the morally best and politically and strategically effective answer to most policy problems must take into account what the people who are affected by those answers think. It may not be a satisfying answer, but the answer to the question of what we learned from studying public opinion on war is that we must study it. Understanding what people think about complex moral and strategic problems like war also gives us some indication of what it takes to cue people to have pro-humanist and pro-peace attitudes.

Is unilateral abolition the ideal?

If we fully appreciate the immense destructive power of nuclear weapons use, including the risk of nuclear winter, but also simply the effects of nuclear exposure on the human body, then to me, there can be no doubt that the morally ideal solution to the problem of nuclear weapons is abolition.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial © Wirestock Creators via Shutterstock

At the same time, advocating abolition is not particularly helpful, because there is no pathway to all countries abolishing their nuclear weapons. Unilateral abolition, if just one or two nuclear-armed countries disarm, is potentially more dangerous than the current situation. In the world we live in, we must engage in what a philosopher might call non-ideal theory, asking what is the best possible outcome to work toward from the position that we find ourselves in? That is: we have nuclear weapons in the world. There are several states that have them, nine states altogether, with different regimes, different cultural backgrounds – states that are involved in conflicts and geopolitical tensions. These states are not likely to all give up their nuclear weapons.

Preventing nuclear use

What is the least bad outcome we can work towards right now? I think we need a multi-pronged strategy. One prong is to educate the public about the consequences of nuclear use.

Hiroshima November 1945 © LTJG Charles E. Ahl Jr via Wikimedia

Even though we do not find that public opinion in many countries follows the logic of a nuclear taboo, publics are sensitive to arguments about the consequences of nuclear use. A public education campaign focusing on all nuclear-weapon states is one important prong to reduce nuclear risk. Institutionalization of safeguards against unwanted nuclear escalation or mistakes in communication would be another prong. Then, yes, a third prong is deterrence. Since we know that nuclear weapons are in the hands of personalist dictators like President Putin, we must also take a hard-headed geopolitical look to prevent a situation from arising in which President Putin’s incentives suggest using the Russian nuclear arsenal. We need hard-headed geostrategic and geopolitical solutions. We must harness the power of moral arguments and of law. All of these things must come together to prevent nuclear use in the 21st century.

Public misconception about nuclear use

A misconception is that the public underestimates the likelihood of a mistake or unwanted escalation. We tend to think that the biggest risk is that a personalist autocrat sitting on a pile of nuclear weapons decides one day to use them and launches a bolt out of the blue. In fact, the biggest risk is either nuclear escalation from an ongoing conventional armed conflict or a mistake, an accident. The propensity for something like that to happen in the long run is quite high, and I don't think we are sufficiently alive to that unfortunate reality.

Editor’s note: This article has been transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author and edited for clarity. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

nuclear weapon deterrence

Dill, J., Sagan, S. D., & Valentino, B. A. (2022). Kettles of hawks: Public opinion on the nuclear taboo and noncombatant immunity in the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Israel.. Security Studies, 31(1), 1–31.

Dill, J. (2015). Legitimate targets? Social construction, international law and US bombing. Cambridge University Press.

Dill, J. (2023). Threats to state survival as emergencies in international law. . International Theory, 15(2), 155–183.

Dill, J., Sagan, S. D., & Valentino, B. A. (2023). Inconstant care: Public attitudes towards force protection and civilian casualties in the United States, United Kingdom, and Israel. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 67(4), 587–616.

Tannenwald, N. (2007). The nuclear taboo: The United States and the non-use of nuclear weapons since 1945. Cambridge University Press.