I've been reading the Book of Margery Kempe for over 30 years, and it's a source and a text I keep on coming back to and seeing new things in it. It's the most remarkable artifact from medieval England. I first encountered it as an undergraduate a long time ago. At this time, which was in the early 1990s, Margery Kempe was still a very marginal, forgotten voice. Her book wasn't on the university syllabus. A friend of mine and I had to kind of lobby to spend some time studying her, because she wasn't considered up there with Chaucer, Malory, Langland and the famous medieval English poets as worthy of study. I felt, even then as an undergraduate, that this source telling the story of a 15th century bourgeois woman opened an absolutely unique window onto the medieval past, onto details of everyday life – domesticity, embarrassment, caring for one's husband, food – these really important parts of being alive, and I've stuck with it since then. I find it's an absolutely remarkable source.

Margery Kempe: a medieval voice

Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Literature

- The Book of Margery Kempe is among the earliest named English life narratives and offers a rare female voice on domestic life, spirituality and pilgrimage.

- The sole surviving manuscript vanished for centuries. It was rediscovered in the 1930s in a Derbyshire country house during a ping pong game, which sparked modern study and the recovery of women's voices from the Middle Ages.

- Kempe carefully shared her visions within church limits during fierce anti-heresy campaigns, facing real threats of being burnt yet presenting her work as divinely ordained.

- Her candid descriptions of mental distress, erotic devotion and caregiving make the book pivotal for the history of emotions and relatable today.

Why Kempe matters

British Library Gate © C. G. P. Grey via Wikimedia

Manuscript’s rediscovery

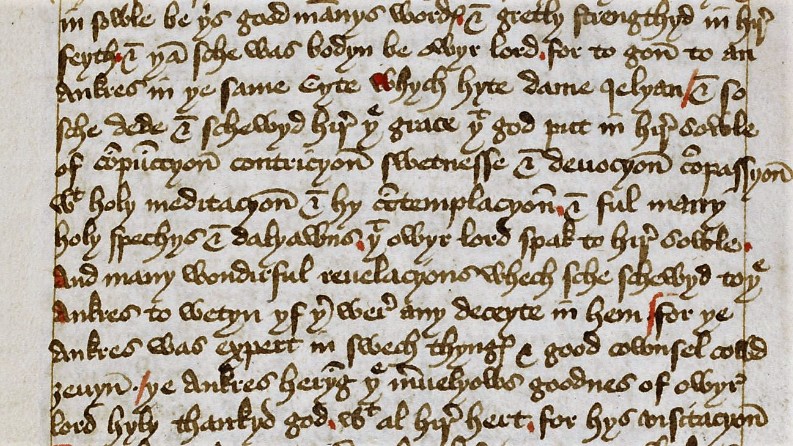

In the 1430s, when she's probably in her 60s, she has the book written down. The original manuscript of the book no longer survives, but a slightly later copy from Norwich Cathedral survives now in the British Library, and this manuscript disappeared until the 1930s. In the 1930s, it was rediscovered when a group of people were playing ping pong in a country house in Derbyshire. Someone stepped on the ball and they went looking in the cupboard for a new ball. Two medieval manuscripts fell out, and one of the people there happened to work at the Victoria and Albert Museum and took it to the museum over the next few days and consulted with his colleagues. There it was identified by an American medievalist called Hope Emily Allen as The Book of Margery Kempe, which had been missing for hundreds of years.

The Book of Margery Kempe, Chapter 18 (excerpt) © British Library via Wikimedia

It's a very dramatic and romantic story of how it was rediscovered. Her book was not well studied until the 1980s and 90s. As well as the amazing story of the book itself, there's also this important story of its retrieval, which is partly a feminist story of the retrieval of women's voices from the Middle Ages.

The first English autobiography

The Book of Margery Kempe is often described as the first English autobiography. That's a slightly complicated term because there are earlier texts like Mandeville's Travels, which are written in the first person, even if they're not historically accurate, and Margery Kempe certainly didn't write her book herself. She couldn't physically write.

Miniature from the Rupertsberg Codex of Liber Scivias © Wikimedia

She needed several scribes to write it down for her. I think it's fair to say it’s the earliest named story of someone's life, of a woman's life, from medieval England. Even if it's not the earliest, it's an absolutely remarkable source. It tells the story of Margery Kempe. She's a historically attested woman who was born in the late 14th century in the town of Lynn, now King's Lynn in eastern England, then one of the larger towns in England and a very important port with connections to Flanders, Prussia, the Baltic and the Hanseatic League, and she was quite well off in her background. Her father had been the mayor and a member of Parliament and was involved in a lot of trade between England, Gdansk, Stralsund and Lübeck, the Hanseatic towns of the Baltic coast. She wrote her book when she was an elderly woman looking back on her life. It describes a kind of mental, spiritual and physical crisis after she had her first child, her development from being a jealous, acquisitive merchant's wife into a mystic and into having spiritual conversations with Jesus, God, the Virgin Mary and the saints, and turning herself from what we might think of as a worldly person into a spiritual person. This takes the form in her book of great torment, great humiliation, lots of spiritual conversations with confessors and advisors, and also a remarkable set of pilgrimages to Rome, Jerusalem, Santiago de Compostela, through Europe and around the British Isles – which are an ordeal for her but show her in an imitation of Christ as developing her spiritual authority through being an outsider, being mocked and being scorned.

Kempe’s female agency

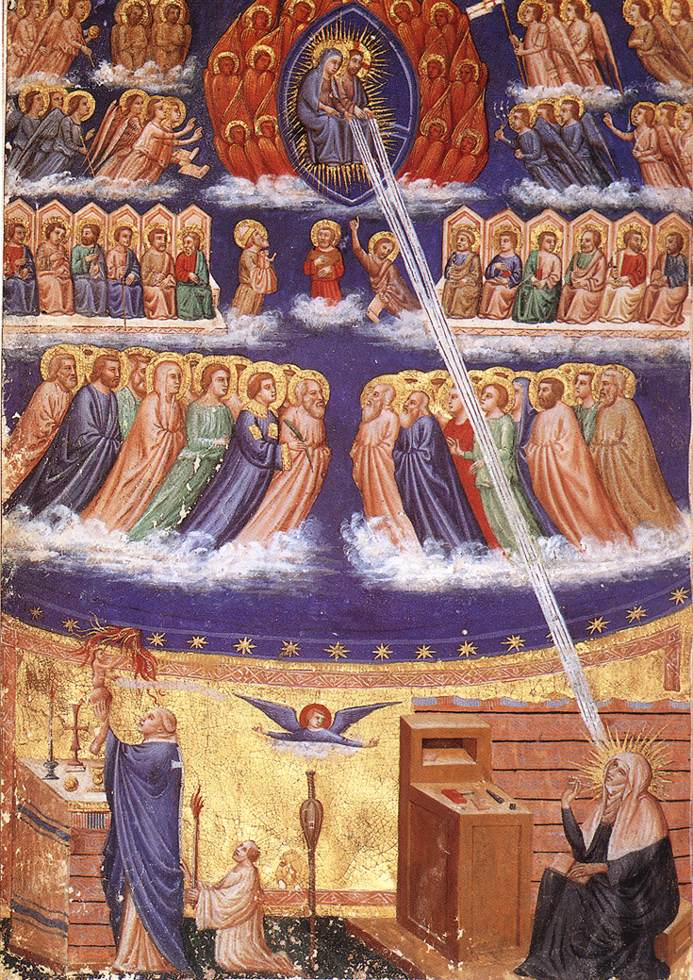

There are a lot of different aspects to Kempe's female agency that can be partially retrieved from the book. One of these things is that, at least in part, she models herself on other holy women, particularly Saint Bridget of Sweden, also to some extent people like Catherine of Siena or Francesca of Rome, various female exemplars from the 100 or 150 years previously that she had modeled herself on.

Revelations of St Bridget of Sweden © The Morgan Library & Museum via Wikimedia

This includes some of her distinctive kinds of spirituality: crying, wearing white clothing, marrying God in a ceremony of betrothal that she does in Rome – all of which you can see other female saints doing. She's putting herself in a relationship with people who had been well-known mystics or saints, women from recent times. These are mentioned in her book as some of her favorite spiritual figures. Part of what she's doing is constructing herself as a holy woman in that established model.

Avoiding accusations

As a woman, she can’t preach, following Saint Paul and the Church’s teachings on women’s roles, and she has to be very careful about not being mistaken for a heretic. At this time, the Wycliffite or Lollard heretics are kind of what are often called a proto-Protestant congregational group. They did have a much greater role for women in them, of reading and expounding on the Bible, and Kempe has to be very careful, because the punishment for Lollardy, for Wycliffism, could involve being burnt to death. It could involve a very high-stakes trial. As a woman, she has to be very careful to negotiate different kinds of limits on her authority. She is also married and from an elevated social position. She has those social bonds of expectations of behavior, which are also putting pressure on her. When she decides to write her book in the 1430s, she makes it clear that this is divinely ordained. This is something that God wants her to do. This is not something that she necessarily has chosen for herself, and she waits a long time to have it written down. What she's doing is writing about her experiences as being remarkable, as being instructive, and she wants them to be useful to her readers as the story of how one discerns one's spiritual journey, whether it's from God or whether it's from the devil, how one actually understands visionary experience.

Margery Kempe and Joan of Arc

The question of Margery Kempe and Joan of Arc’s parallel or historical relationship is really interesting, because we know that they are both active and alive at the same time. There are some very clear correspondences between their experiences about hearing mystical voices, about changing one's clothing, about the allegations of heresy. John, the Duke of Bedford, pursued both of them, and he was one of the people who ultimately led to the execution of Joan of Arc. Earlier on, he had also pursued Margery Kempe as a heretic, even though she definitely wasn't a heretic; he had pursued her in northern England, and she describes this in quite a lot of detail.

Joan of Arc interrogation © Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen via Wikimedia

They're part of the same historical moment, which more broadly is about the regulation of the divine, of spirituality, and the regulation of charismatic people – not just women but in this case two women who have a charismatic spirituality, who demand to be heard and to intervene in their society in ways which are troubling to the authorities. In Margery Kempe's case, this is to do with the atmosphere in England at this time, with the regulation of thought in the light of Wycliffism and Lollardy, which is about enforcing the uniformity of the Catholic Church. This includes things which are uncontroversial to Kempe, like the veneration of saints, the importance of pilgrimage, the existence of purgatory, the transubstantiation of the Eucharist – these are all things that Kempe clearly believes. The Wycliffites, or the Lollards, also very much believe in vernacular scripture and vernacular translation, vernacular preaching; Kempe comes quite close to those things. They have these secret, or forbidden, what are called conventicles – meetings around prayer and preaching – in which women and men take part. There's the sense that Kempe is proximal to this kind of culture of lay English preaching. The regulation of what one thinks, the regulation of thought crimes, is very rigorously enforced in both Joan of Arc's and Margery Kempe's time by the same people, by the English authorities.

Threat of heresy

In the late 1420s, from around 1425 to 1432, Kempe's book is almost silent about this period. It says almost nothing. Kempe never mentions Joan of Arc and says very little about the English wars in France and the situation there, even as she travels through Calais and elsewhere. Her book is very quiet about the late 1420s and the period around 1431. This is the time of the most intense heresy trials in Norfolk as well as what's happening in France.

The capture of Joan of Arc on 14 May 1430 © Bibliothèque nationale de France via Wikimedia

Her book discreetly draws a veil over this. It's tempting to think that she or her scribes thought it was still very dangerous territory. Kempe is threatened with being burnt at the stake many times, including publicly by strangers, often by women. This is a language which hovers over the whole book. It's important to note here that Joan of Arc's execution was unusual but not unique. The first person burnt in England at this time, under a new statute called de heretico comburendo, on the burning of a heretic, was a man called William Sawtry, who had been the parish priest at Kempe's church in Lynn and certainly would have been known to Kempe – if not closely related spiritually to Kempe. There is a possibility that she was quite closely linked to some of the people who had been burnt in England. For a modern audience, we need to remember that being burnt to death was not a kind of abstract threat. It was something that was quite real at this time.

Medieval emotional life

The Book of Margery Kempe is a really important document in terms of the history of emotions, because Kempe is so varied and free with describing different kinds of emotional states. On the one hand, she describes, in Middle English terms, what it meant to be mentally distressed — what we might now call mental illness.

She describes going out of her mind with distress during her first pregnancy in the aftermath of her giving birth to her first son. She describes in great detail this moment of distress for her, which includes her biting her own hand and leaving a scar there which she has for the rest of her life. She also describes how this is when she has her first vision of Jesus, and she says in Middle English that she was steadied in her wits by this vision. She is given a kind of consolation, which gives her emotional peace.

Comunione Santa Caterina © Museo Reale d'Arte via Wikimedia

Jesus appears, sits on the end of her bed, calms her down and then disappears again. He appears as an incredibly good looking man. She repeatedly describes in the book Jesus as this very sexually attractive and physically available presence to her. She also describes her husband in sexual terms, and she describes this mortifyingly embarrassing episode where a man at her church asks her to have sex with him. She says yes, and she goes to meet him to have sex with him, and then he says, no, I was only joking; I was only testing you. Very closely linked to her spiritual, erotic life is also this public life of embarrassment and shame and mortification that she talks about in great detail.

Uncontrollable crying

Perhaps her most important emotional expression is crying. She cries throughout the book. Her crying is social; it's performative. It makes an intervention with other people. She receives what she calls the gift of tears.

Mary Magdalene weeping, © Pethrus via Wikimedia

In Jerusalem, when she's in Calvary, she receives this gift from God, and her crying is uncontrollable. It's noisy; it's expansive. It annoys people, and it's her signature move. It's a way of claiming space, of claiming the conversation without using words, of articulating her whole body. She often talks about her heart as this kind of touchstone, this focal point of emotion. Words like joy, distress, fear and pain appear throughout The Book of Margery Kempe. We often think about the history of emotions not as something which goes unchanged through history. Emotions are themselves historically bounded, and The Book of Margery Kempe is a very useful document in understanding what emotions meant in early 15th century England.

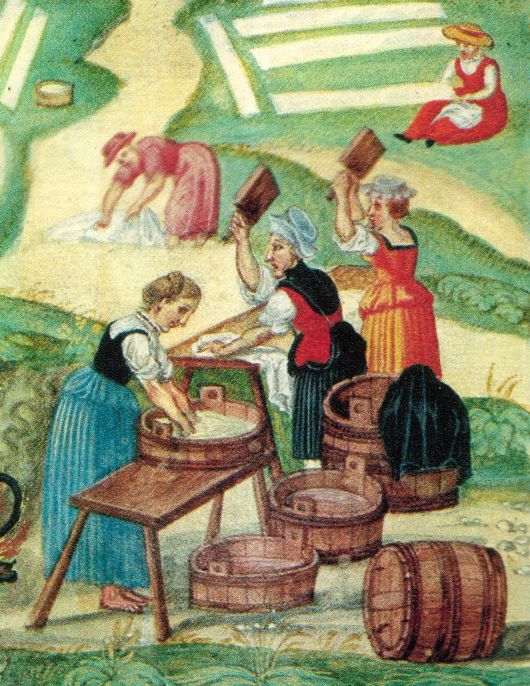

Honesty and compromise

Kempe's book is, on the one hand, her own account of herself. On the other hand, it's an amazing historical document about identifiable people, places and times that is really useful to us. It sticks with us as a very personal account of a person moving through their life. That, to me, is almost unique from medieval England, and the things that Kempe includes I still find very, very moving and striking as a historian. For instance, she describes how her husband in his old age falls down the stairs and suffers a head injury, and she has to care for him. This is unique as a medieval source in a wife talking about her husband's dementia in old age. It's incredibly frank. She talks about how expensive it was to keep on having to clean all the linens, keep him by the fire and dry things, and how unpleasant it was for her that he became incontinent, and she had to clean him up.

Das Grosse Waschfest vor der Stadt, Splendor Solis, 1531 © Wikimedia

This is actually an experience of aging, of old age and of ill health, and of care in marriage, which we don't see in other sources from the Middle Ages – and often it's very hard to talk about today. She also talks about her misgivings around this but then reminds herself that she'd had so much sexual pleasure from his body when he was a young man that she should repay this now, as part of her marital contract and debt to him in her care for him. Also having that voice of doubt, that voice of obligation, is really how we all feel when we're interacting in our relationships, in our changing, and how relationships change throughout life. I don't want to say that Margery Kempe is a guide to how we can live today. There are moments of honesty and moments of compromise in it, which I think really speak to us today. For me, seeing her frankness around embarrassment and her frankness around shame, which are really crucial parts of being a social human being, of being a social animal, and having that from the Middle Ages is unparalleled and very touching. The modern reader can, with the caveat of historical distance, also think about subjectivity through The Book of Margery Kempe in a way which is absolutely unique.

Socially determined emotions

Readers coming to Margery Kempe for the first time are often very irritated by her emotionality, her emotional expression. They say there's too much emotion. It's put on. It's embarrassing. It's over the top. We ought to remind ourselves that all emotions are historically determined, and the language we use to describe our emotions is of our own historical moment. When we use very common emotional language today, for example, we might say, “I'm dying to go shopping. I'm dying to go to that concert,” or we might use a superlative of an emotion. In historical terms, that might be unprecedented. People are actually very, very careful about the rhetoric and the language of emotions that they use in the historical moment. Kempe's emotional lexicon is very precise. She uses particular words like joy to describe a particular moment of spiritual union, not just happiness. She uses tears in strategic ways but also in expressive ways.

The Mater Dolorosa, Aelbert Bouts, mid 1490s © Fogg Museum via Wikimedia

I would remind readers of The Book of Margery Kempe, and I'd remind people thinking about their own emotions and emotions in the past that our emotions are not natural, and the ways we express them are not natural. They are socially determined; they are historically determined. The way we express emotions today might look ridiculous to people thinking about us in 100 years' time.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

Margery Kempe

Bale, A. (2022). Margery Kempe: A mixed life. Reaktion Books.

Bale, A. (2017). Richard Salthouse of Norwich and the scribe of The Book of Margery Kempe. The Chaucer Review, 52(2), 173–187.

Kempe, M. (c. 1430.) The Book of Margery Kempe. Translated and edited by Windeatt, B.A. (1985), Penguin Classics.