The way we greet and the way we part are essentially the same. We shake hands, we kiss, we hug, we wave. At least we used to do these things; we have elbow bumps now. But the same gestures and, often, the same words – “ciao”, “shalom” – are used at greeting and at parting. Even “adieu” is used as a greeting in France. So there must be an inherent relationship between the things that we are dealing with when greeting and when parting.

These are mini rituals that frame an encounter. It is all too easy to move beyond them, to start thinking about the meat of the encounter, and to forget that this has been framed by a greeting and by a parting. A lot goes on at these moments. They condense a huge amount into tiny gestures and the choice of words that are used.

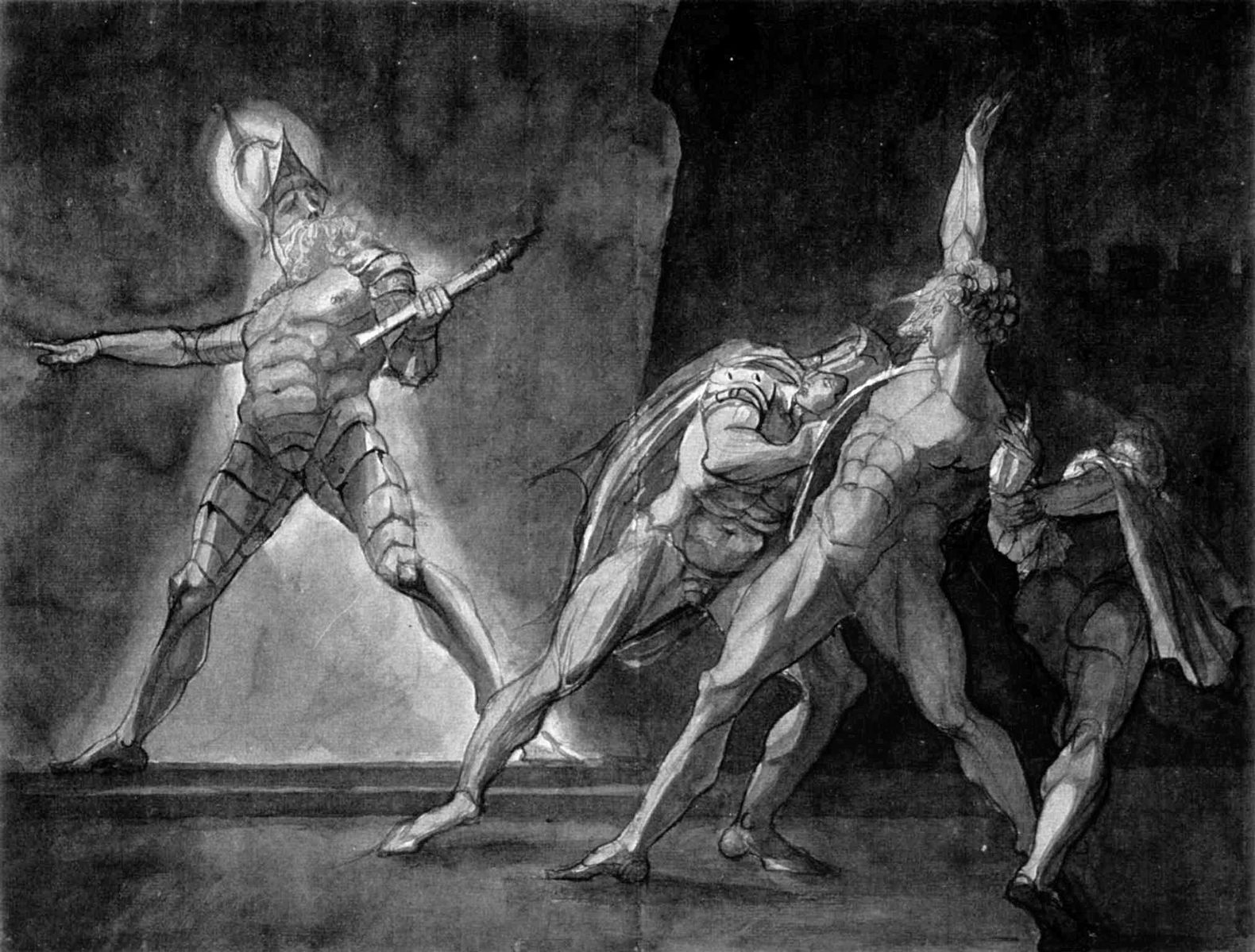

Shakespeare knew this. His art involved constantly having people encounter one another – beginning scenes, ending scenes, sometimes entering scenes in medias res – but all the time, actors have to come into and move out of relation to each other. What a director does with those moments is quite important to a production.

When we greet or part from the other, when we encounter the other, the first decision takes place in almost no time at all. We have to decide: friend or foe? There’s a spectrum. Do we want to embrace the other, or do we want to kill the other? At the extreme ends, there’s a sex or death choice at that moment. We’re not aware of this most of the time; these moments are precisely designed as rituals to keep at bay the enormous emotional intensity of meeting another human being.