We are very international and I think I have been privileged to be part of this international community trying to understand the world and the universe. I have done this in a university, but I have had the privilege of working with younger colleagues and also working with colleagues all over the world. Of course, in astronomy, like in particle physics, we sometimes depend on very expensive bits of equipment which have to be shared internationally. That makes our subject especially international, and for me, that has been a bonus.

Science as a calling

Emeritus Professor of Cosmology and Astrophysics

- Science involves piecemeal efforts and the international collaboration of many people to understand what’s happening in a particular area of the natural world.

- Scientists have a responsibility to realise when their work may have a dangerous downside and guard against its use.

- Many decisions made by politicians today have a scientific element, so in order to have democratic debates, it’s important that all citizens have a feel for science and statistics.

- We have got to bear in mind that life has a vast future and we cannot conceive what type of intelligence may exist billions of years from now, not just here on the Earth, but far beyond.

Straddling boundaries

I have been a scientist specializing in the field that has developed very fast, so although I do not feel I have made any great individual contributions, I have been part of a debate, which has, over the last half century, really deepened and broadened our understanding of the universe we live in. When the history of science is written, what has been learned about the universe in the last 50 years will be one of the real high points, along with the double helix and genetics and Darwinian evolution and various other things like that. I have been privileged to be part of a debate, which of course is an international debate, because science is an activity which straddles boundaries of nationality and faith more easily than other activities.

General Assembly of International Astronomical Union © IAU via Wikimedia.

Piecemeal efforts

Imagination is certainly crucial. Much of our work obviously is in a sense fairly routine, following up ideas, gathering lots of data, etc. It is not all inspirational, but insights are clearly important, and you have got to have an imagination to decide which ideas look promising and which are just crazy. So that is where judgment comes in, to actually have a feel for what ideas are likely to prove fruitful and also which ideas can be tested, because, of course, the feature of science is that it is not just conjectures; it is conjectures which are tested and verified or refuted by experiments.

© ESO/Yuri Beletsky via Wikimedia.

One important point is to pick topics to work on which are in a sense bite-sized. They are not too big to tackle in one go. To give an example, if you ask scientists what they are doing on a particular day, they probably will not say they are trying to cure cancer or they are trying to understand the universe; they would say something which looks rather specific and detailed. They realize that you can only tackle the big problems in a piecemeal way. Only cranks or maybe one or two geniuses can solve a big problem in one go. So science involves piecemeal efforts by the collaboration of many people to understand what is happening in a particular area of the natural world. That is a satisfaction, because I think the social aspect of science is very important for many of us.

A dangerous heresy

It is important to realize that our everyday lives depend on scientific discoveries made often a century or so ago. There is a long transition between a discovery and its incorporation in technology we all benefit from. Of course, the people who do the technology are not the same people as those who do the original thinking. Of course, one should not be snobbish about this. Sometimes people think there is something especially rarified and deep about what pure scientists do as compared to what engineers do; that is a very dangerous heresy. In fact, my engineering friends like a cartoon which showed a picture of two beavers looking up at a huge hydroelectric dam. One beaver says to the other, I did not actually build it, but it is based on my idea. That, I think, more accurately reflects the balance of effort and intellectual power between having an idea and working it through and developing it, so it is actually useful and beneficial. Obviously the same person is not qualified to do the whole transition; many people are involved. It is an obligation on scientists to think about whether their work has a beneficial use and try and foster the application of it. Not by doing it themselves, but by showing that it is taken up.

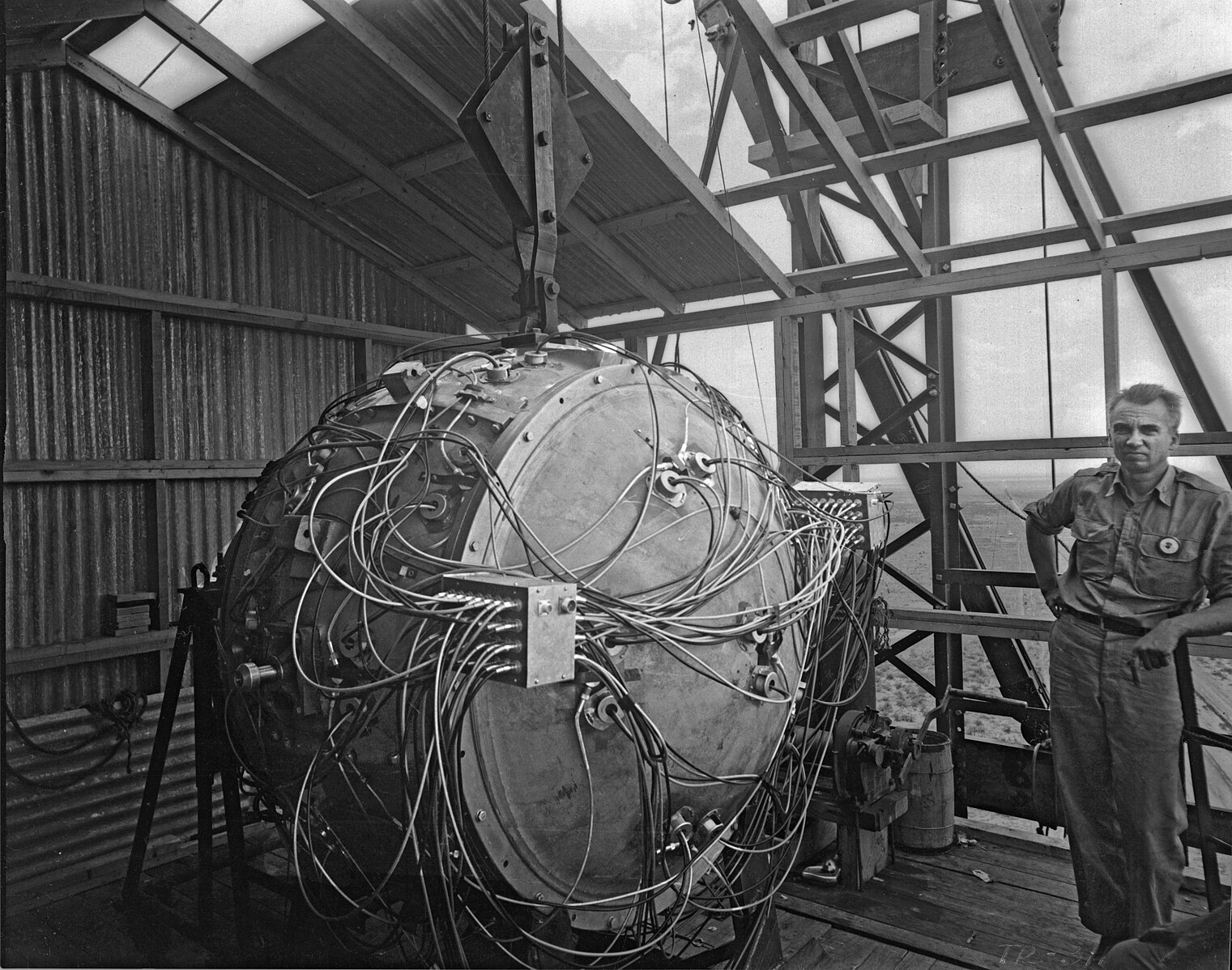

Norris Bradbury, group leader for bomb assembly at Los Alamos. © US Federal Government via Wikimedia.

Even more important is to realize that if their work has a possible dangerous downside, they guard against that being used. There were cases like that; I think there are cases now, in terms of biotech, when people realize that it is becoming easier to generate, to create, dangerous pathogens. The classic instance when that happened was, of course, in the 1940s when scientists realized it was possible to make an atomic bomb. This, of course, was made at Los Alamos in the 1940s. The world has been influenced by that ever since.

Obligation to limit harm

I have been privileged to know in that 80 years some of the scientists who were involved in making the first bomb. Sadly, they are all deceased now, but they were great individuals and many of them were academics, and they returned with relief after the end of World War Two to their universities and laboratories, but they did not regard themselves as cut off from the world.

Chicago Pile One scientists at the University of Chicago on December 2, 1946. © Wikimedia.

They felt they had an obligation because of their special knowledge to help control the powers they had helped unleash. It was some of these great scientists, names like Hans Batur, Joseph Rotblat and Rudolf Pyles, three I was privileged to know. They tried to promote arms control. They started something called the Pugwash Movement, which was a gathering of scientists from both sides in the Cold War, Russian scientists and American scientists, which tried to promote a dialogue and feedback to their governments. That was an instance of where scientists showed social responsibility in feeling they had an obligation to ensure that ideas they helped to develop did not have disastrous consequences, but had benign consequences. There are more and more cases where that is going to happen. So we have got to be aware that all these modern technologies, bio, cyber and AI in particular, are benignly developed, but that those involved in them are mindful that they do have downsides and they do what they can to guard against those.

Science for citizens

When we do any experiment which is exploring conditions which did not exist in the past, we have to be careful that we do not have any severe downside. For instance, if we make a dangerous pathogen which might spread in a way that viruses do, then we have got to be quite sure that it does not escape. So scientists have to be very careful indeed if they do something where there is even a small probability of there being a downside. So that is very important. Another point I would make about science is that I think even though professional science is going to be a minority pursuit, I think it is very important that everyone, all citizens, has a feel for science, because it is clear that more and more of the decisions politicians have to make have a scientific element to them, be they on energy, climate, health or the environment, and if we want to have democratic decisions where the debate involves all citizens and gets above the level of just slogans, then everyone has to have some feel for science and for numbers and statistics in order for the debates to be a serious one. One good feature of the COVID-19 pandemic is that in many countries the scientists have become media stars. They have become familiar trying to explain to the public what the issues and uncertainties are. This has helped the public to get a feel for science that is not always cut and dried.

Stephen Hawking delivering a speech entitled "Why we should go into space" for NASA's 50th Anniversary. © NASA/Paul Alers.

Scientists are often groping for the truth, and their understanding develops year by year, even month by month. It is important that the scientists are listened to when their expertise is relevant, and everyone is aware that they are often themselves rather uncertain. Also they must be aware that when politicians have to make a decision, then the scientific input is crucial. Of course, so is the input from ethicists and from economists as well. Of course, in those fields, scientists are just citizens and they have no expertise. So scientists realize that their expertise is important, but they should realize that politicians make a decision based hopefully on the best science, but also taking into account other areas where scientists cannot provide any special background.

Interconnectedness of everything

One remarkable feature about our world is how complex it is and how beautiful it is. I mean, there is no particular reason a priori why you might have imagined that the biological world is so intricately complex with millions of species, flowers and trees and all the rest of it, and the huge variety of animals.

Red-eyed Tree Frog Agalychnis callidryas. © Al Carrera via Shutterstock.

We would not have predicted that, but it is amazing. Also, when we look up into the sky, we see stars of huge variety behaving in different ways. We realize that all this is interlinked in an intricate way. We would not exist if the stars had not made the atoms that we are made of. So we need to understand the stars, as well as the atoms, in order to understand the everyday world. What is wonderful is the interconnectedness of everything and how this intricate complexity has emerged from simple beginnings many billions of years ago.

Humans in space

One of my special interests is space science, and of course I am therefore very closely a follower of what is happening regarding sending humans into space, as well as sending instruments into space. Of course, human space flight reached its peak more than 50 years ago, when the Apollo program landed groups of Americans on the moon. That was the high point of manned space flight; now people have been in low Earth orbit in the international space station, but there has been no revival of space exploration by humans beyond low Earth orbit. Now, it is an important question: is that going to happen?

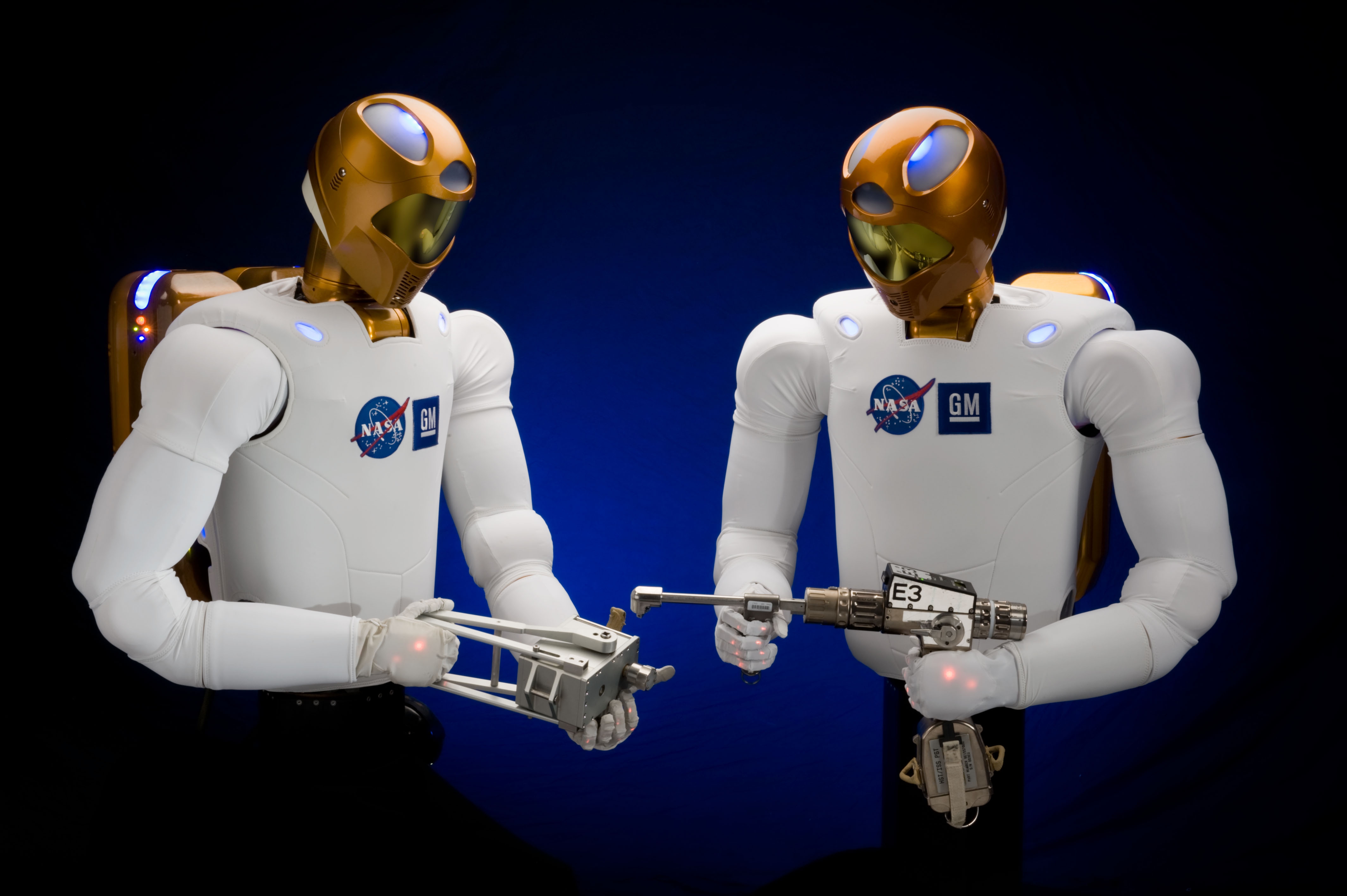

Humanoid robots. © NASA/Robert Markowitz via Wikimedia.

The motive is going to be reduced, because the gap between what humans can do and what robots can do is narrowing. Up till now, humans can do far more in terms of exploring the surface of Mars or fabricating some structure in space than a robot can. That gap is going to close. Let me bear in mind that it is far, far cheaper to send robots than to send humans; I think the practical case for sending humans into space is going to get weaker.

Towards a new species

Living on Mars is as uncomfortable as living at the top of Everest or on the bottom of the ocean. I do not think mass emigration ever makes sense because the atmosphere of Mars is 1% of the Earth's. It is not breathable and the gravity is different, etc. If we look a bit more futuristically, then those pioneers on Mars will be important in cosmic history, because by the end of a century, we will have the technology to modify the human genome and to design humans different from the present ones.

Futuristic human colonization and exploration of Mars. © Frame Stock Footage via Shutterstock.

This is a technology which I hope will be regulated on Earth for prudential and ethical reasons. Those people on Mars are away from the regulators, and because they are ill adapted to the environment there, they can probably use the technologies we will have by the end of the century of genetic modification, perhaps cyborgs, interfaces with machines or electronic computers, to adapt themselves. Within a few hundred years, they will have become a new species. Then, if they become a new species which has a far longer lifespan, they could adapt to Mars and they can voyage further away, maybe into the blue yonder, beyond our solar system.

Our vast future

© Shutterstock.

We have got to bear in mind that life has a vast future. The Earth has been around for four and a half billion years, but it is less than halfway through its life. It has got to go another six billion years, and during that time, the amount of evolution that can happen may be as dramatic as from the first protozoa to humans, as it was over the last four billion years. So we just cannot conceive what type of intelligence may exist billions of years from now, not just here on the Earth, but far beyond.

Editor’s note: This article has been faithfully transcribed from the original interview filmed with the author, and carefully edited and proofread. Edit date: 2025

Discover more about

Science as a calling

Lightman, A. and Rees, M. (2025). The Shape of Wonder: How Scientists Think, Work, and Live. Pantheon.

Rees, M. (2022). Is Science to Save Us?. Polity.

Goldsmith, D. and Rees, M. (2022). The End of Astronauts: Why Robots Are the Future of Exploration. Harvard University Press.

Begelman, M., & Rees, M. (2020). Gravity’s Fatal Attraction: Black Holes in the Universe (3rd ed.. Cambridge University Press.

Rees, M. (2002). New Perspectives in Astrophysical Cosmology (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.