The participation articles

The participation articles of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child have served an importance far beyond what anyone imagined. These articles have enabled children to see themselves as rights holders who are vocal about their rights. These articles on participation have also been a powerful mover of all of the other associated rights.

Most people are familiar with the article that states children have the right to be heard. Still, there are other participatory articles worth knowing as well: on the freedom of expression, freedom of religion, freedom of association, freedom to assemble and organise, on the right to reliable information and, finally, on the right to know their rights, which is the foundation of them all.

It’s worth stating what Article 12 articulates since this right to have a voice is the one that most people refer to as having had a significant impact on children’s rights globally: ‘States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views, the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.’ It then explains that children should have the opportunity to be heard in any judicial or administrative proceedings, either directly or through a representative.

Marta Santos Pais was the secretary of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child at its launch, and she said that she never anticipated the sweeping impact Article 12 would have. However, we now realise that it provides an underlying value to interpreting all of the Convention and that children’s opinions need to be respected and encouraged.

The questions are: What is the quality of the settings we give children? What affordances do we give them and when? What opportunities do we give them and what support do we offer them?

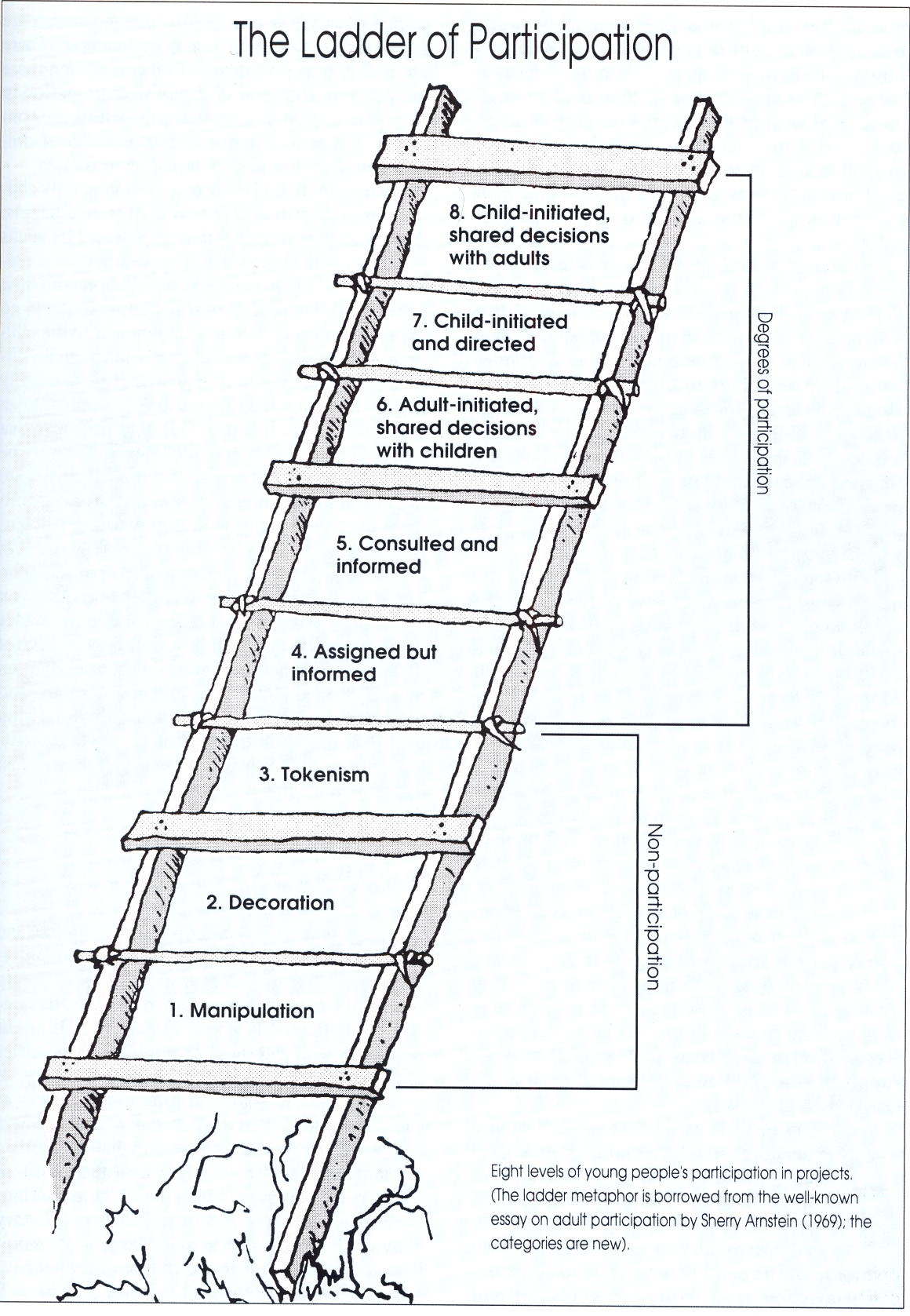

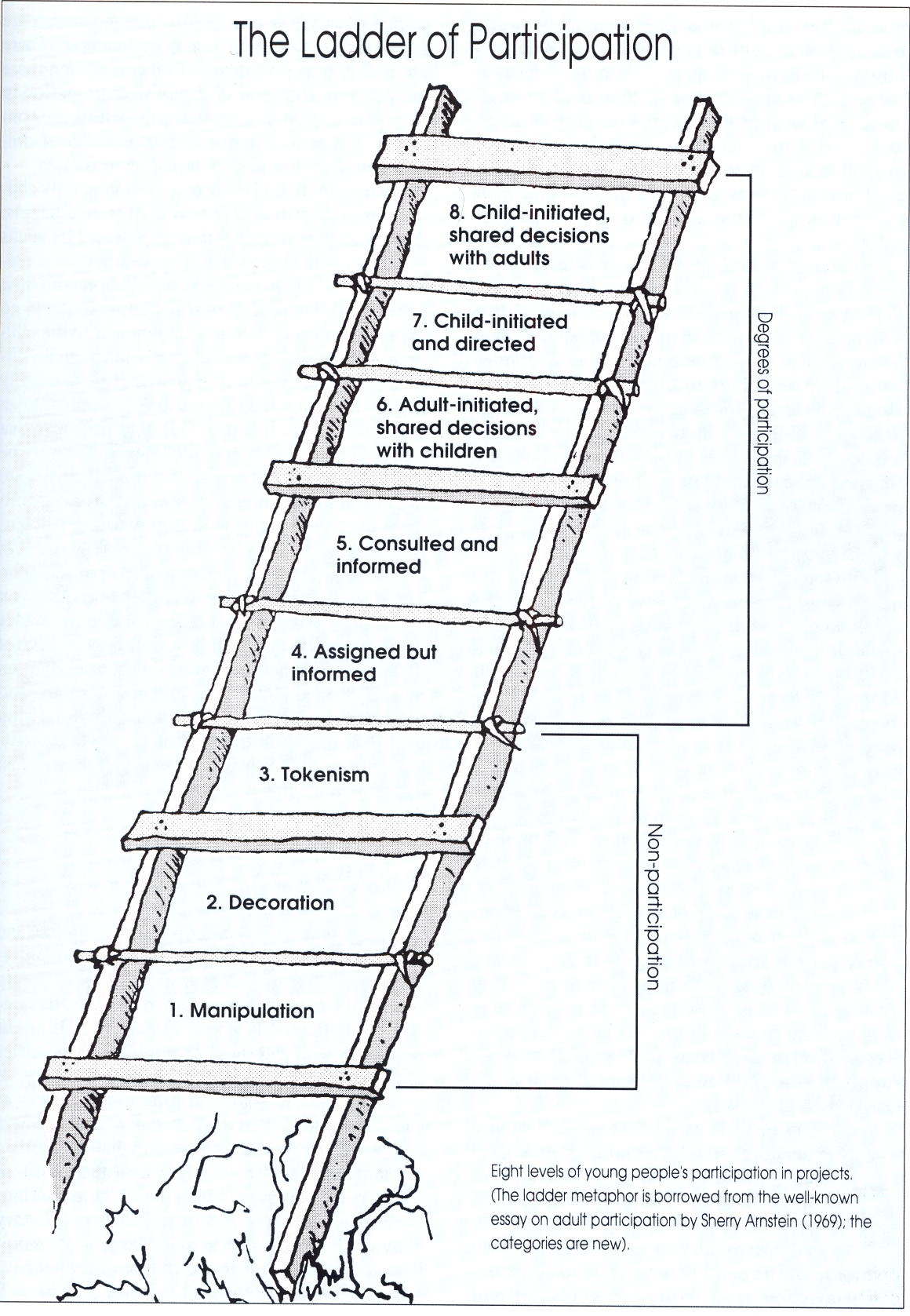

The ladder of participation

© Roger Hart

There are no experts on this question that cuts across many of contemporary society’s most significant issues. We, academics, continue to struggle with it. I began to try to understand what was wrong with children’s participation more than 10 years before the ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. My work centred on the planning and design of children’s environments, which continues to be a major part of my work today. I discovered that research studies on spatial ecology and the use of children’s play environments wasn’t enough to change the way planners design neighbourhoods and public spaces.

I found that trying to find ways to involve children (and parents) directly in the planning and design of environments was more valuable. However, when I looked for instructive literature on working with children and giving them a voice, there was hardly any. I then began to observe that when people did involve children, it was often in a tokenistic or manipulative way. Consequently, I drew a ladder for a newsletter that we produced for colleagues to try to make sense of it all; I called it the “Ladder of Participation”.

I’m going to try to explain the Ladder of Participation by giving a step-by-step introduction to it, beginning from the bottom of the ladder up. The Ladder contains eight rungs. The bottom three rungs of the ladder are not genuine participation and should be avoided. We call these “inauthentic”. Then, there’s one transitional rung called “social mobilisation”, followed by four more rungs on top, which I consider to be “genuine participation”.

The lowest rung: manipulation

The lowest rung of the ladder is “Manipulation”; for example, when young children carry political messages in demonstrations without any likelihood of knowing the message they’re bearing. While it may seem harmless, it does not afford children a real voice, so it should be avoided. Some of the children are merely misguided rather than manipulated. They haven’t thought their actions through because adults have influenced them to care about a cause that they aren’t familiar with.

Thus, why shouldn’t we put children in the march? We should recognise that even young children have opinions; they may be able to express how they would like to participate or what the theme of a demonstration should be. If so, they can then make their own posters and proclaim their particular concerns without adult direction.

I witnessed this when I was looking for ways to involve children in environmental planning and design. Those architects who claimed to do a design with children typically gave them pieces of paper to draw their favourite play places. They then took those drawings away and somehow synthesised them into completed playground designs, which they attributed to the children. Not surprisingly, their playgrounds looked just like most other playgrounds. The adult architects used the idea of children’s participation to support their work and pretended that the children had inspired their design, which I consider manipulation.

Decoration

The second rung of the ladder, “Decoration”, is very common. Children might be invited to participate in an event concerning children, such as a conference, through singing or dance on an unrelated theme, for the viewing pleasure of the audience. Suppose the event is focused on an issue that they might have their own perspectives on, like the improvement of schools. In that case, it’s an unacceptable missed opportunity not to allow them to use the performance time to creatively express their perspectives on the theme of the event in a manner that suits them, such as mini skits.

Tokenism

The next rung of the ladder, “Tokenism”, is tricky because it often happens when adults are trying to give children a voice, but the adults do it in a way that is unintelligible for children. It doesn’t give children time to formulate their opinions and make a clear articulation of what they know about the issue. Adults don’t offer the children many choices about how to participate.

Tokenism also happens with international agencies, including the United Nations. It’s common for children to be selected rather than elected to go to speak at a conference. Often, they only find out about the conference’s theme a short time before they’re supposed to present their opinions. Adults pretend that these superficial beliefs represent the real voices of children when they don’t. The young presenters could more authentically express their perspectives if they were afforded enough time in advance to gather with their peers to discuss their concerns with one another.

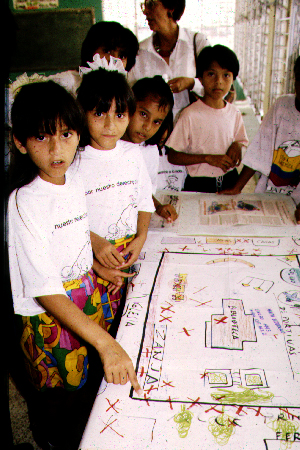

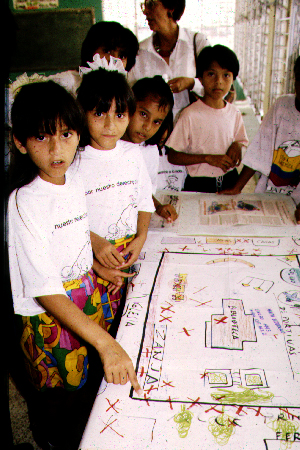

Social mobilisation

© Roger Hart

The next rung of the ladder is “Social Mobilisation”, which is transitional to truly engaged participation. With social mobilisation, children are typically used to increase the number of participants in an initiative; serving as accessories to the adult organisers. It is necessary to look closely at such examples and at the particular culture where they are used, in order to ask to what extent, they are participatory. Take, for instance, a pro-vaccination march: children may not fully understand the issue or how essential it is, but they’re told that it’s vital for them to march in it for the rights of other children, so they’re urged to wear propaganda T-shirts and join the line. While this can be valuable as a public awareness mechanism, it’s not an ideal introduction to having a voice. On the other hand, if organised differently, the children may be more fully informed about it, feel like they have real ownership of the issue, and even have some critical reflections about it.

Acceptable participation

The next rung of the ladder is the beginning of acceptable participation: “Consulted and Informed”. The children understand the intentions of the project and volunteer to participate. They are aware of who made the decisions and why, and therefore, play a more meaningful role. This kind of transparent, informed consultation is higher up on the ladder since children are offered a platform to advise. It has become quite common in some countries. For example, local governments in the United Kingdom arrange consultations for children, through such mechanisms as interviewing them in groups, or through hearings where children get to ask politicians questions rather than politicians consulting them.

All of the upper rungs of participation are acceptable. Children can’t always be expected to want to operate at the highest levels of their competencies on all matters. “Adult-initiated, shared decision-making” – the next rung on the ladder – processes with children are common. Good teachers do it all the time. For instance, they’re planning a sports event, but don’t want it to be like all the others they’ve ever had. Therefore, students and teachers get together and plan it together.

© Roger Hart

The seventh rung on the ladder is called “Child-initiated and Directed”: when children think of something by themselves that they would like to initiate and carry out. We know that children can operate at this high level because even pairs of preschool children can initiate and coordinate their play activities with one another.

The eighth, final, rung of the ladder is called “Child-initiated, Shared Decisions with Adults”. Children should not only feel competent to initiate their own new projects but to also feel comfortable inviting adults to join them. This is not placed at the highest level of the ladder to imply that it is the best kind of participation, to which children should always aim for. The higher rungs are simply ways for me to articulate the degree to which children should feel that they have the right and capacity to aspire to them when they wish.

Street workers and playworkers, like progressive teachers, are impressive in their ability to work alongside children and understand their participation rights. Playworkers serve as somebody children can talk to if they have any questions or concerns. They remind children that they have a right to invent games and that they don’t have to follow what others say. These playworkers respond to children’s desires by enabling them rather than directing them.

Street workers listen to children who live, or work, on the streets, and respond to their needs. If the children say: we need to learn and we don’t have a chance to learn because we’re shining shoes all day, what can we do? We need a place where we work to learn. The street worker might suggest setting up a blackboard near where these children are shining shoes. By establishing a good relationship, and affording children with opportunities to feel comfortable independently identifying issues that they would like to change, the streetworker had been operating at a high level of participation.

The ladder is valuable for its simplicity. I tried to create a simple tool that provides a vocabulary for recognising the issue of child participation without giving all the answers. The ladder allows people to see that participation isn’t so straightforward and should be critically considered.

Misunderstandings with the ladder

Sometimes, people first look at the ladder and assume that the higher rungs are better and that children should always seek to operate at the highest possible level. That’s not true. Although operating in the bottom three rungs cannot be called participation, any of the rungs from social mobilisation up are equally acceptable as ways for children to influence or make decisions.

Another one of the ladder’s problems is that some people think that the highest rung is bad. People wonder why adults should be involved when children should be in charge. My answer is that when I drew the ladder, I didn’t believe that being in charge was the most sophisticated way of interacting with the world. I never meant that children no longer needed to listen to adults nor that they should have nothing to do with them. On the contrary, once they’re competent, able and confident enough to initiate projects and carry them out on their own, why not sometimes invite adult citizens to also be involved with them?

One exemplary project of child-initiated shared decision-making involved young mothers and pregnant teenage girls in a youth group in an impoverished community on the edge of Brasilia. After discussing how they loved their children but wished they weren’t having babies at such a young age, they decided to make a video and to ask adults for technical help. The video was influential in raising awareness because other girls felt it was more authentic and convincing to hear from the girls like them than from the words that they commonly heard from adults.

Children participating in democracy

School councils are a common form of children’s participation that might seem like a good idea for listening to the perspectives of children. Still, they have significant problems as democratic structures. They tend to involve only the popular children, and administrators are usually not clear in advance about which domains children can and cannot influence in school decision-making.

Fortunately, there are now many more democratic initiatives by children than there are school councils. International children’s organisations used to try to improve children’s lives by delivering them projects. The organisations would invite children to a workshop on, say, bullying, by providing refreshments, food and education. These might be important and valuable workshops, but they often failed to address the issues that most concern the children because of their top-down design. Since the launch of the CRC, agencies like Save the Children, World Vision and Plan International, have discovered that children like to work in groups and talk more openly about their rights.

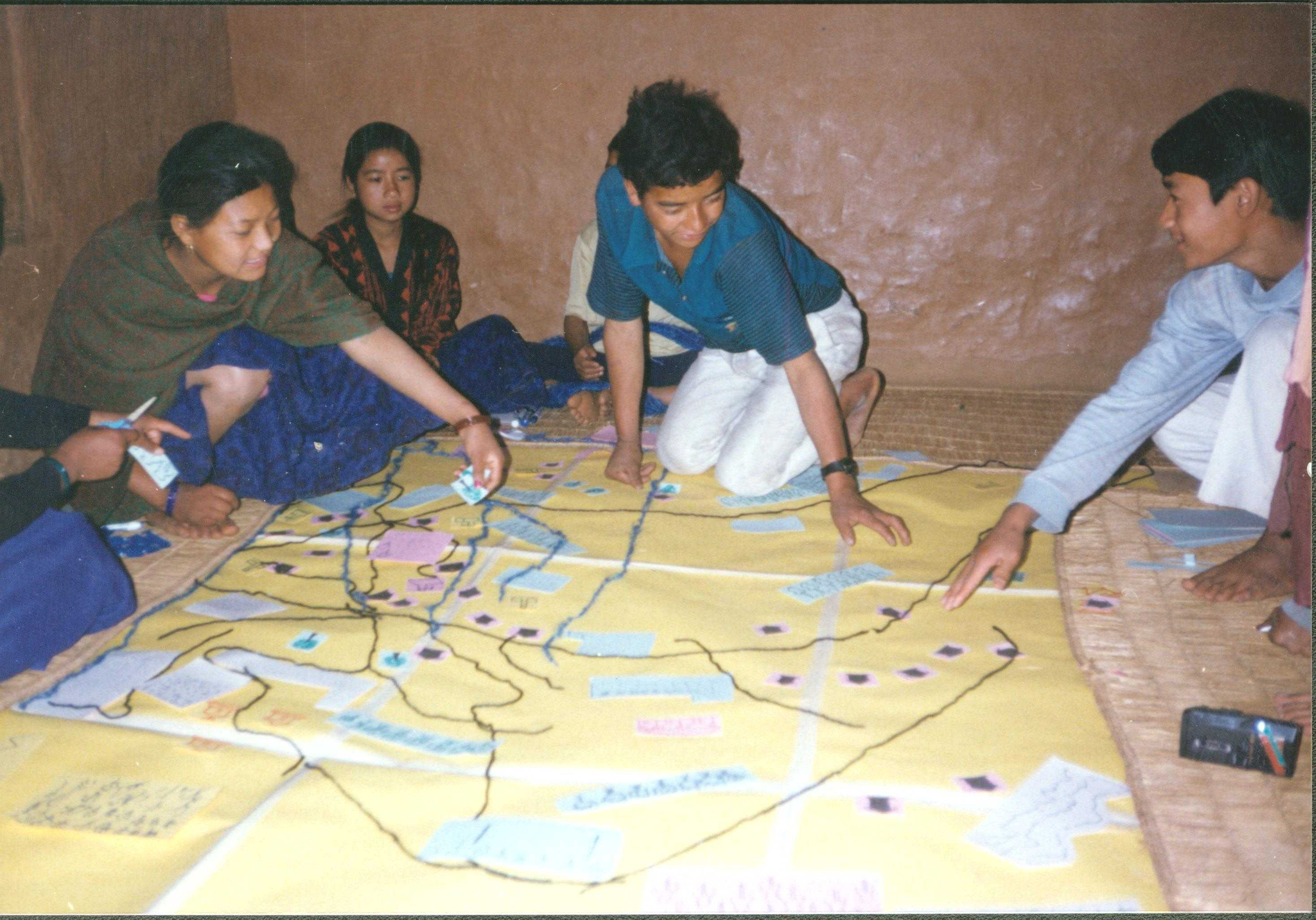

One day I got an invitation from Save the Children working in Nepal. They had offered workshops to communities throughout the nation, to introduce children to their rights. The children enjoyed gathering to have discussions together so much that they expressed the desire to continue to meet regularly. International agencies couldn’t possibly respond by organising and running hundreds of children’s clubs, so they did something that was undoubtedly better. They supplemented their workshops on children’s rights with minimal training in how to organise, and then simply left the children alone, visiting only occasionally. To their amazement, these Nepali children’s clubs not only developed as democratic organisations on their own, but the clubs proliferated to other villages.

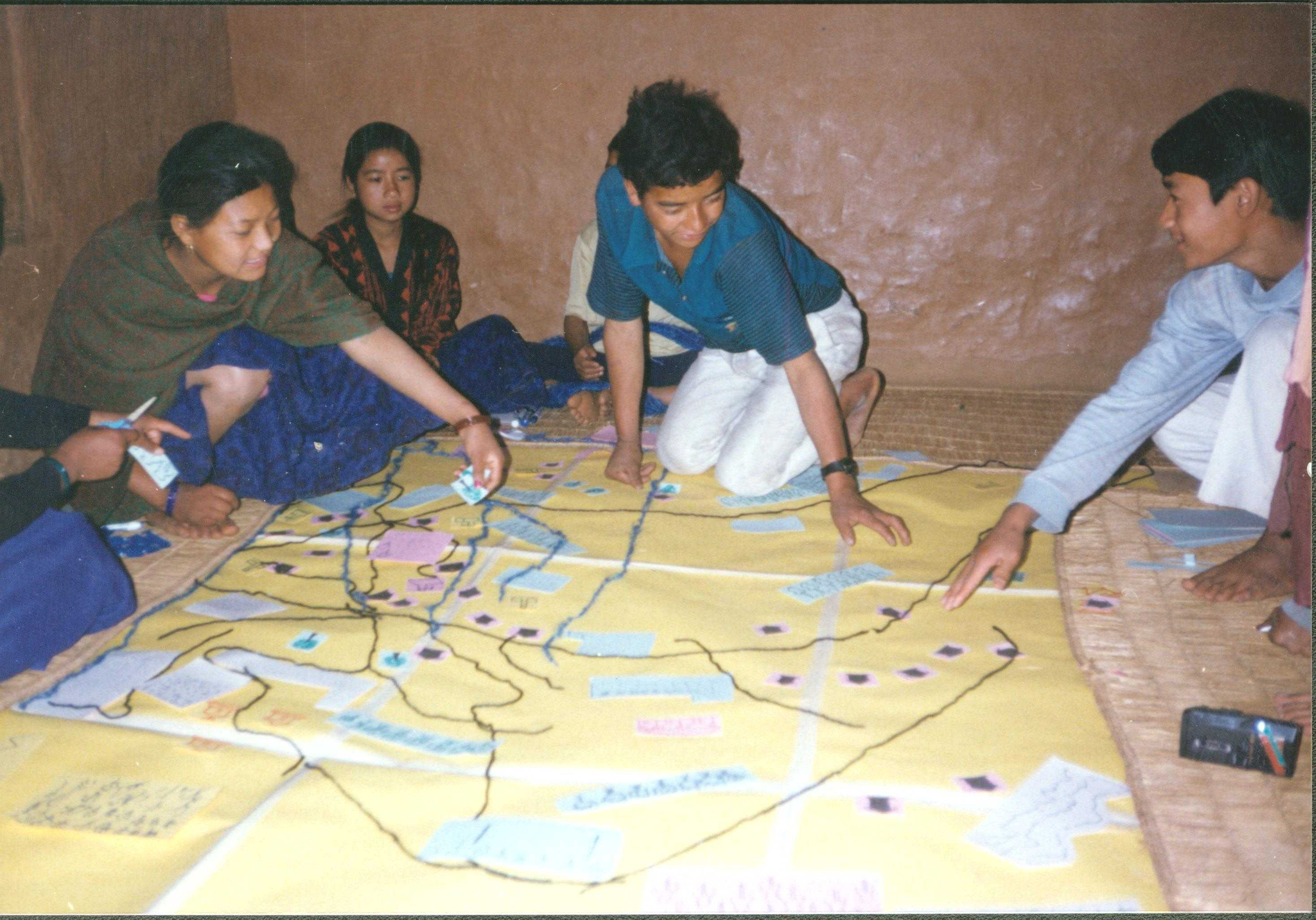

Working with Nepali organisations

© Roger Hart

In the first village I arrived at, in the mountains, not a single adult greeted me. Instead, children ran out of the village to greet me. They took me to a building that they had a key for, introduced themselves and explained their political structure in an organised and coherent way. It was delightful to see such genuine local self-organisation. I developed methods, including pictorial graphs, social maps and skits, with my Nepali colleagues, to enable children to critically examine how they function as democratic institutions. They revealed a thoughtful, self-critical understanding of organisational structures, including issues of inclusion and gender balance. I was impressed by the sophistication of the Nepali children’s clubs and how they had creatively developed structures and processes to be able to function relatively independently as rights-based children’s organisations.

We travelled all over the country and learned that the clubs had benefited from the children’s observations of their mothers’ participation in the Nepali women’s groups, which had developed in their villages over the prior years; they were highly democratic settings to advocate for women’s rights. Children had often attended their meetings, which had no doubt helped them to understand the meaning and value of autonomous organising. The result was that while men continued to serve in Nepal’s positions of authority, they now worked alongside powerful women’s associations and children’s clubs.

A right to vote?

© Gino Santa Maria

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child tells us that children have the right to have a voice on all matters that concern them according to their capacity. People often wonder why children can’t vote until they’re 18 – a question that I was asked by the BBC a few years ago when Prime Minister Tony Blair was starting a debate about reducing the voting age to 16. It didn’t take me long to think that 16 was an acceptable age to participate in elections. According to child development theory and research, children can think about complex ideas by the time they’re 16. They’re also able to take others’ perspectives and incorporate them into their perspective, which makes them ready to think about political issues and have their opinion heard.

Perhaps, I could be convinced that we should allow children even a little younger than 16 to vote, but certainly before 18. If we wait until after 18, children will have left school, and lost an excellent opportunity to have extensive classroom debates with one another about societal and environmental issues. Once they start a job, who knows what chance they’ll have to have that kind of conversation. Although there are arguments for and against lowering the voting age, it would ensure children another opportunity to get their voices heard and rights fulfilled.