The growth of an environmental movement

Photo by Jossfoto

The environmental movement of the1960’s gained energy in 1972 with the launching by the UN of World Environment Day. It was an important moment, but the movement was then linked to a rather simple-minded view that Earth’s environmental problems could all be solved through environmental conservation: if we could just save wildlife and stop polluting and degrading the environment all would be fine. It failed to recognise that humans need to make a living off the environment and that we can’t just tell people of the world’s poorer nations to conserve environmental resources when they feel that they have too few of those resources to survive and thrive in the first place.

In 1992, the UN organised another world environmental conference, this time in Rio de Janeiro, commonly referred to as “The Earth Summit”. It began to incorporate the different environmental concerns of the poorer nations. “Agenda 21”, the Rio Declaration on the Environment, offered a more complete environmental perspective, called “sustainable development”. Sustainable development brought together the three pillars that we need to consider when thinking about our behaviour in relation to the environment: environmental protection and enhancement, social progress and economic development.

Children’s right to survival

Young people today know about both sustainable development and children’s rights. When we bring them together, you can understand why a lot of students feel that they have the right to go on strike. The sustainable development agenda interrogates how societies can live in a manner that allows them to meet their needs without compromising the needs of future generations. We now have strong voices from young people, like Greta Thunberg’s, who feel that they have the right, and responsibility, to speak out about this because they are the future generation. Greta has been a powerful instigator for many others due to her modesty, free of media manipulation, combined with her passionate commitment to the need to change our behaviour towards the environment. Greta and several other children recently went to meet the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child in Geneva to make the argument that Earth’s environmental crisis is a children’s rights issue.

The need for a radical change

Photo by Rawpixel.com

People, across generations, are more fearful for the future than they’ve ever been before, and this is galvanising young people’s involvement. Children probably learn more about our relationship to the natural world from watching disturbing stories on the screen than from environmental education in schools. They are told by much of the mass media that future technological innovation will solve our problems but, fortunately, not all young people are convinced by that. They are increasingly aware that we all need to also rethink how we behave in relation to the environment and how governments make policies on our behalf.

We need a radical transformation of environmental education in schools that can match the passion that children are increasingly feeling for the subject. Children acquire an informed and caring ecological perspective through being able to directly explore and critically observe and evaluate their local ecosystems. However, in many industrialised countries, the greatly reduced independent mobility of children means that they lack the freedom to explore and independently learn about their environment. Schools, generally, do nothing to address this problem. Environmental education in schools is based on instruction with textbooks. Children largely learn about distant environmental problems in the abstract while ignoring local ones.

Another major structural problem of school curriculum is that they separate science and social studies when the concept of sustainable development clearly needs to be addressed jointly by these different disciplinary domains. Schools still organise lessons on the environment using a natural sciences lens and usually fail to include a social justice approach that acknowledges the need to address inequities in peoples’ access to environmental resources.

Local Environmental Study

All schools, whether or not they are in rural or inner-city locations, need to allow their children to directly study their local environment. Since many children no longer have opportunities to safely explore their local environment independently from their home, the onus on schools to do that is greater than ever.

One exemplary model is in the deeply democratic “New Schools” (Escuela Nueva) of Colombia. These alternative schools were established for children in the coffee-growing regions 30 years ago because they weren’t able to go to school every day since they needed to help with the harvest. The local farming communities had their own strong local democratic structures. They wanted their children to be able to maintain this by learning democratic governance, as well as how to care and manage their local ecosystems. Experts from all over the world came to help design a flexible, highly effective, democratic model for schools. The result was not only children who excelled academically but also children who felt a high degree of ownership of their school and had the democratic skills to carry into the care of their larger community. When I visited these schools for the first time, it was a child who greeted me upon my arrival and began to introduce me to the school environment and community.

The Worm Farm Committee of an Escuela Nueva.

© Roger Hart

The children were highly organised into committees and showed me the projects they’d undertaken. At the Escuela Nueva, committees include all the children, unlike in the typical, exclusive school councils. They have committees for nutrition, for the school garden, for the worm farm with individual plots, as well as for the fish farm and so on. All children can expect to serve on committees, not just the chosen few.

In these rural communities of Colombia, children were even able to talk about the problems that they had with the local village government, run by men of the village. For example, in one community I visited, the Fish Farm Committee argued – in ways that all of the children understood – for the need for a fish farm at a different altitude because they wanted to bring in fish that weren’t suited for the altitude of the current fish farm. The Escuela Nueva is a successful example for a rural agricultural community. We need more examples of schools in urban, as well as rural settings, that can help bring children into a critical engagement with their local environment that results in improved understanding and care for the environment and helps the community move further towards engaged local democracy. It will be more of a challenge to develop this model for cities, but the Escuela Nueva movement has been gradually making progress in this regard.

Studying urban environments

© Roger Hart

During the 1970s and early 1980s, the Town and Country Planning association in the UK designed an initiative that involved school teachers and urban environmental educators from all over the country. A brilliant planner named Colin Ward ran the initiative. He became an expert on advocating for children to take active roles in meaningful research on the planning of their local environment. He managed to convince planning agencies all over the country to put an officer inside the county planning departments who was dedicated to inviting children to collaborate on environmental planning projects. For example, when a new motorway was under development, he managed to convince schools along the motorway to let their children research the motorway’s environmental impacts. As part of this effort, Ward developed the monthly Bulletin for Environmental Education, for 20 years, with articles written by school teachers from across the country about research and community environmental planning projects by their young students.

The Notting Dale Urban Studies Centre, in London, served as one of the best examples of this powerful initiative. It was a study centre from which children would collect data on housing conditions and all kinds of local environmental problems that were identified by the community. A steadily growing archive of their research at the centre served as a resource for adult planning meetings. Additionally, suburban children visit and sleep overnight in the upstairs of the Urban Studies Centre to learn about city life and community research.

The future of environmental education

In recent years, a burgeoning new educational philosophy has emerged in the USA called place-based education that has the goal of using the local community as the foundation for all subjects. This concept has long been a feature of a small number of progressive elementary schools. However, it has special energy now because it is connected to a larger social movement, outside of school education, called “the new localism” that addresses the decline of community life that we are all facing due to economic globalisation. It holds great promise for the rejuvenation of environmental education, and place-based educators are quite naturally incorporating the kind of local ecological study described in the previous section.

It is ideal, if a local study of the kind described above takes place, for such schools to link with one another. I experimented with this many years ago by linking school classrooms in New York City with classes in schools in Vermont and New Hampshire for an entire year. Each class partnered with a class of children living in a very different environment. Each of the students established pen pals and shared their research regularly with their twin school on the local environmental problems that they were investigating. In their first letters to one another, they drew and described the environment where they lived, shattering many of the stereotypes that they had of each other’s city and rural environments. They identified, through interviews with local residents in each of their communities, places that needed improvements to the quality of the environment. They then studied these places and developed proposals for changes with local community-based organisations. At the end of the year, the classes of students visited each other’s communities and led their environmental pen pals around the sites that they’d been researching all year.

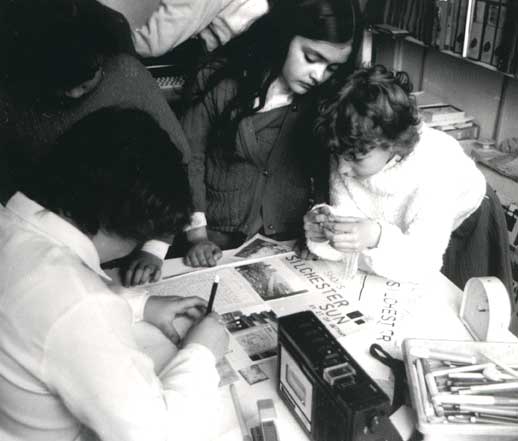

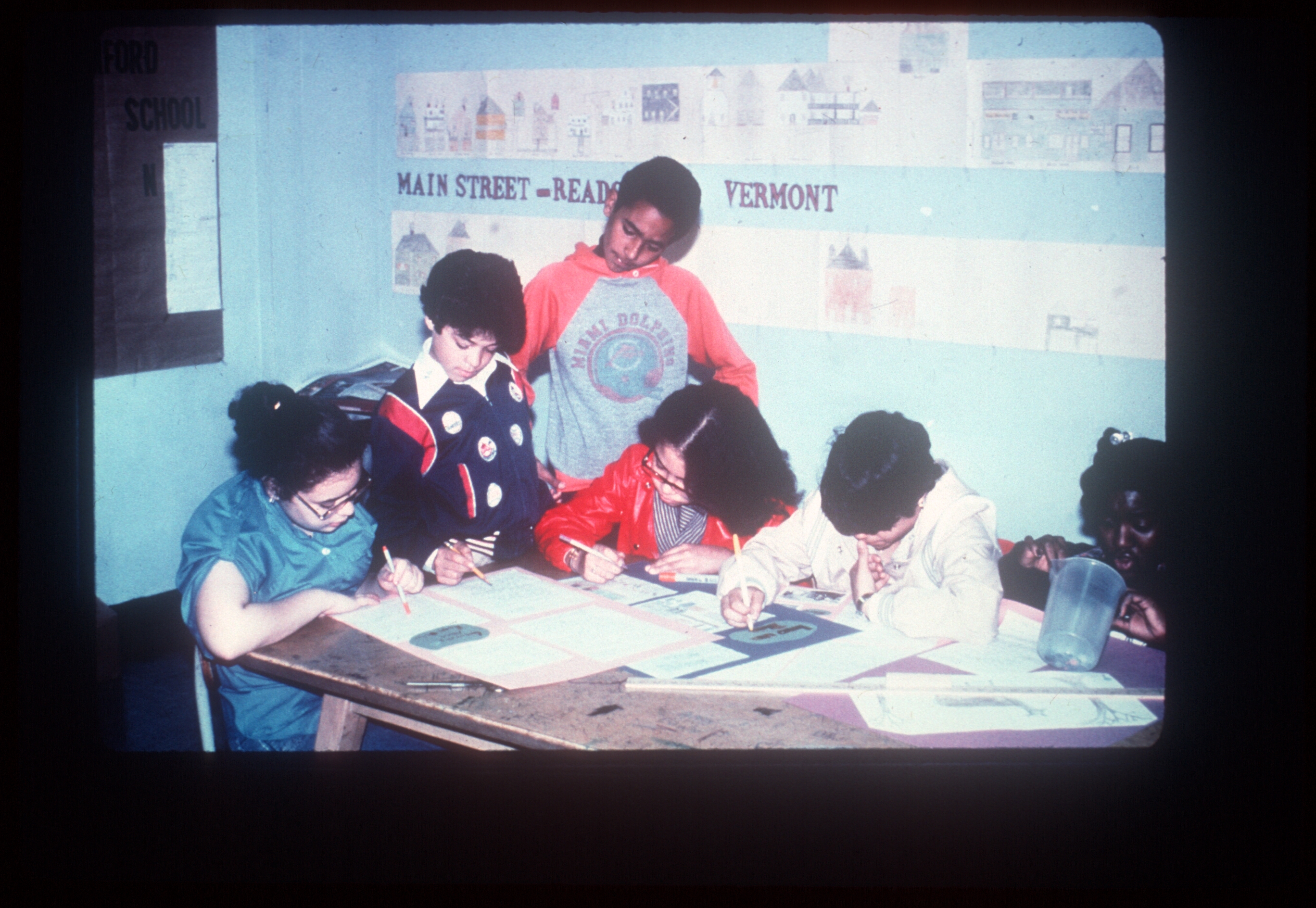

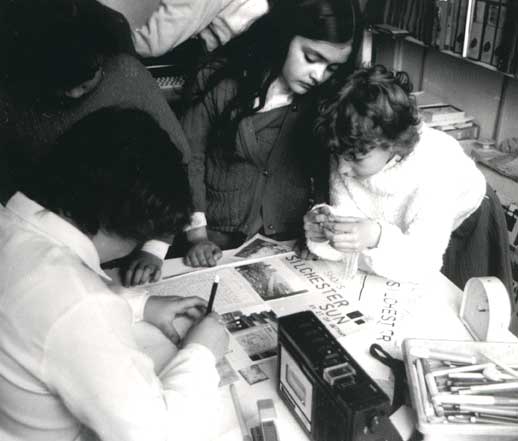

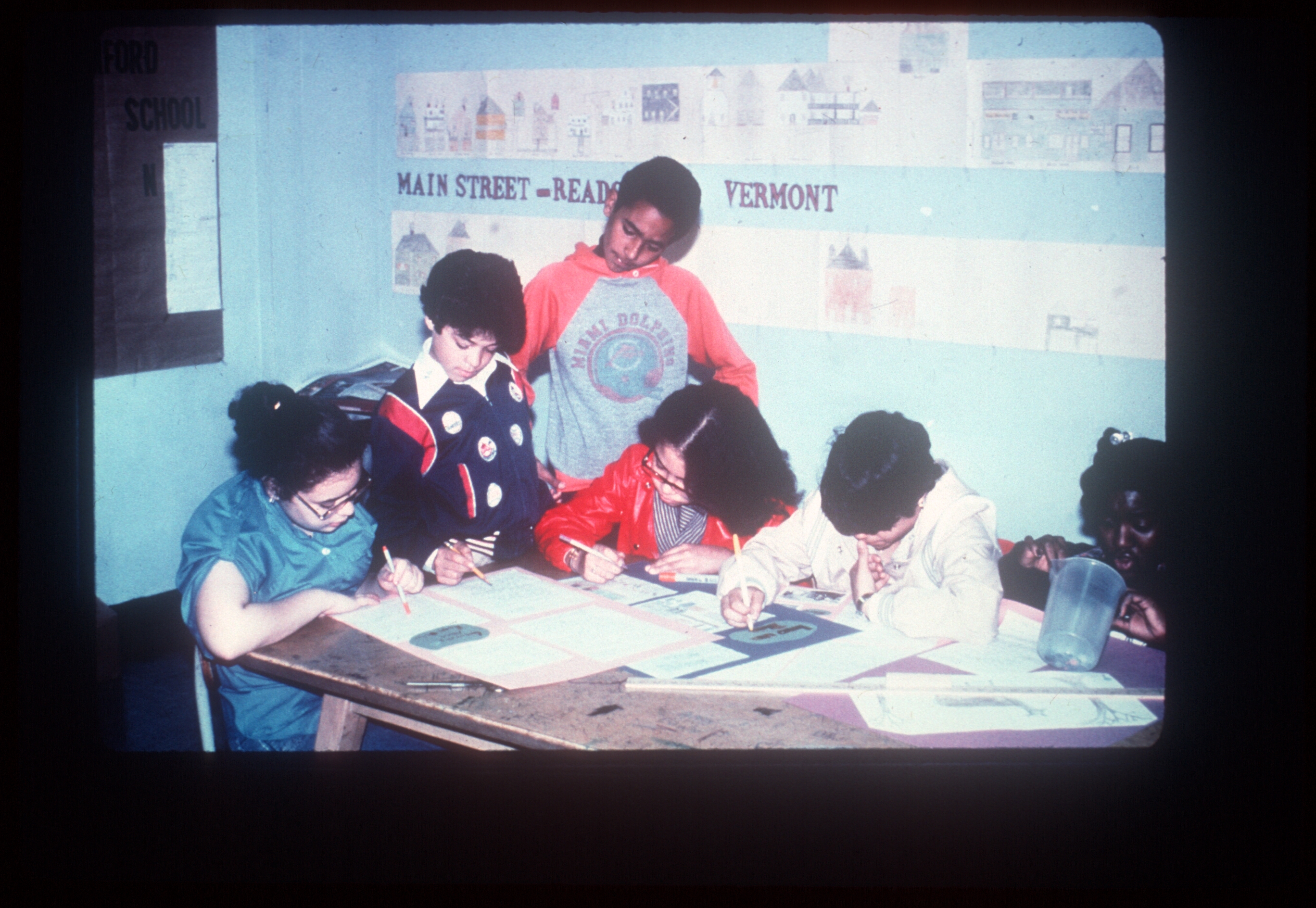

Students in Harlem, New York City writing back to their twin community in rural Vermont about similarities and differences between their two settings.

© Roger Hart

It is also possible, of course, to exchange local environmental research by children on a global scale through email. It’s an effective way to introduce children to the great diversity of environments and environmental issues in different parts of the world. Moreover, some kinds of country exchanges can also have special value in making clear what is meant by the inequity of environmental resources between rich and poor countries. Children learn that you cannot merely export solutions to environmental problems from one culture to another culture. In these ways, children can gradually build, from their solid local studies, a more global ecological perspective.