You model your existence and you model your experience. A child playing with a doll’s tea party or a doll’s house will be modelling their relations with the world. If they make images of that through puppetry or through drawings, they are then extending their expressive relationship with that world that they are modelling in their minds.

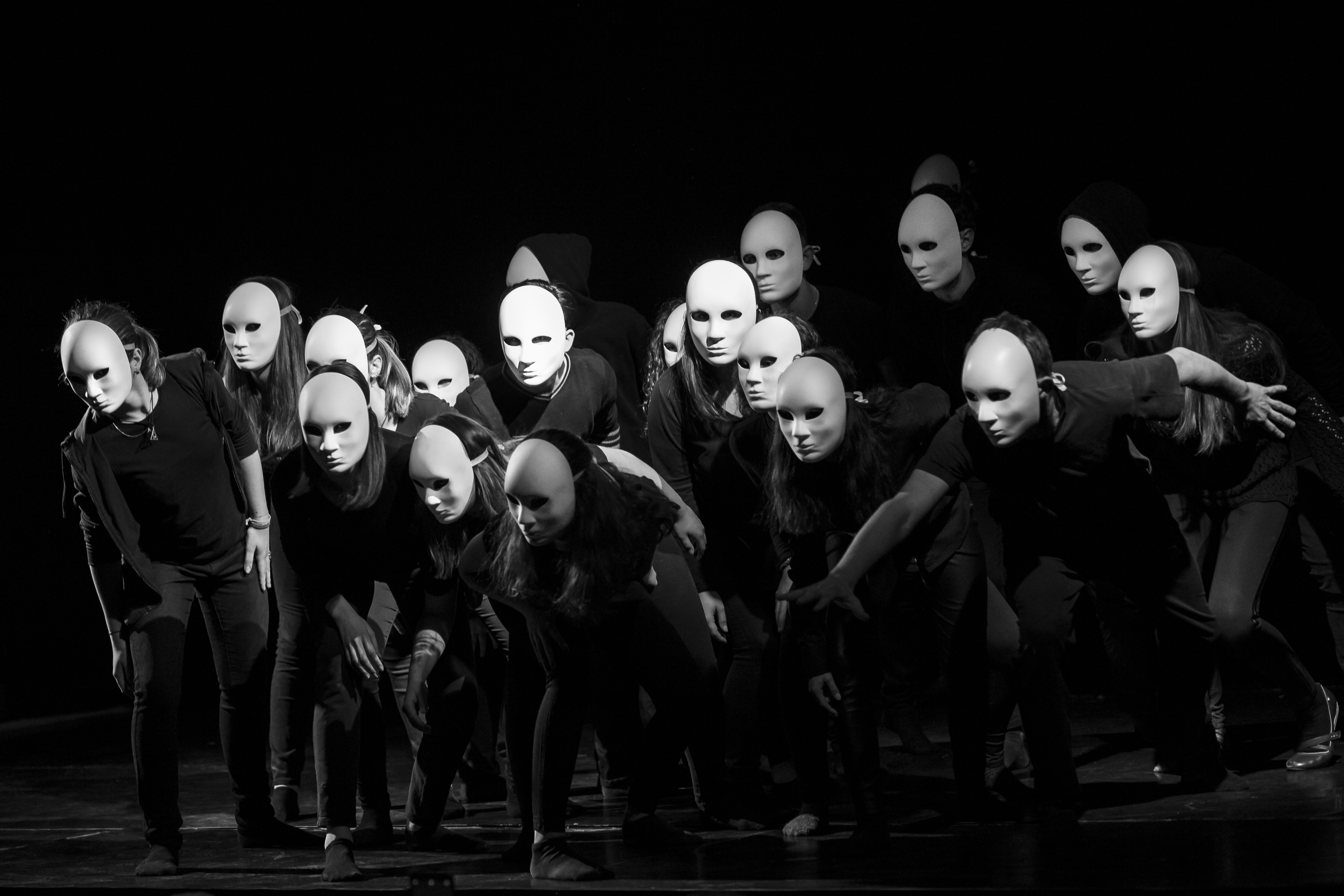

So, there is a way in which the current of imagination, as it flows into a work of art, is a form of play – and that is essential to human well-being. We can express ourselves in this imaginative way. I think almost everybody knows that when you have the chance to make art, it is incredibly satisfying and pleasurable and very, very helpful in a state of melancholy. I think in lockdown people have really thirsted for ways of expressing themselves through making things. There have been successful interventions online. Grayson Perry’s Art at H series on Channel 4 reached a lot of people and it was very well received. Making art is kind of central to sanity. It also has a social dimension, which is that it very often involves doing things together.