De Gaulle is a myth in France today. He’s an extraordinary, all-invasive personality. There are more streets named after him than anybody else. Every politician now needs to refer to de Gaulle, needs to put themselves in the tradition of de Gaulle. This is true even for people who come from very different origins, whether on the left or the extreme right. Everyone is inspired, in some sense, by this towering figure.

Charles de Gaulle and France's nostalgia for greatness

Professor of Modern French History

- The myth of de Gaulle begins with his emergence as a political personality and continues with de Gaulle’s own self-mythologisation.

- Whether from the right or the left, contemporary politicians in France continue to refer to de Gaulle.

- Part of the nostalgia for de Gaulle today is nostalgia for French greatness.

The legacy of de Gaulle

Photo by Anton_Ivanov

Two parts of de Gaulle’s myth

There’s a mythic element to de Gaulle, and we need to divide it into two parts. From the very beginning, de Gaulle was a myth. For the French, between 1940 and 1944, he was a voice that came to them across the Channel, and he was an invisible face. Part of the emotional link that he developed with the French, who were listening to him on French soil while he was in London, came from this strange situation in which he was a voice about whom they really knew very little and on whom they could therefore project their fears, hopes and expectations. So, from the beginning, there’s a curious, mythic quality to the relationship that de Gaulle developed with the French.

Secondly, after the war, de Gaulle was very conscious of wanting to develop that myth. He wrote a remarkable series of three volumes of war memoirs between 1954 and 1958. They are, like all memoirs are to some extent, a process of self-mythologisation. That’s also true about Churchill; it’s true about the famous conversations Napoleon had on Saint Helena. But de Gaulle’s is an extraordinary, self-conscious sculpting of a myth.

A remarkable self-mythologisation

Churchill did something of the same kind, but he certainly didn’t refer to himself in the third person. In de Gaulle’s memoirs, you have a man who opens his book by saying, Toute ma vie, je me suis fait une certaine idée de la France – ‘All my life, I have had a certain idea of France.’ And yet that “I” narrator – de Gaulle – then starts talking about a third person who is called de Gaulle. So, he creates this mythic figure who develops more and more importance during the course of the memoirs.

The de Gaulle myth is something that de Gaulle was very conscious he needed to create. It developed, partly organically, out of the weird way in which he erupts into history in 1950, but which he then plays on. He famously once said to the British ambassador in Paris after the war, Duff Cooper: ‘Every time I look in the mirror, I see the man of the 18th of June.’ And the 18th of June 1940 is the famous broadcast that, as it were, launched him. The French, often as a shorthand, simply refer to de Gaulle as l’homme du 18 juin, ‘the man of the 18th of June’. So, here is de Gaulle saying to Duff Cooper: ‘Every time I look in the mirror, I see l’homme du 18 juin’ – ‘I see the myth.’

A contemporary myth

There is a myth from the very beginnings of de Gaulle’s emergence as a political personality on the French scene; but there is a contemporary myth today, which is slightly separate and difficult to pin down. It’s hard to say why there is this almost obsessive adulation or cult of de Gaulle in France today. I could give two examples of that cult – though cult is perhaps too strong a word and we ought to say reverence.

President Macron has made a lot of references to de Gaulle. If you see Macron’s official Élysée portrait – and all French presidents have an official portrait, which defines their presidency – it shows him standing in the Élysée Palace, where the presidents live, in front of an open book. That book is the war memoirs of de Gaulle. So, Macron is situating himself from his very first photograph in that lineage. I’ve actually tried to blow up the photograph to see what page it’s open at. Unfortunately, I haven’t discovered that, but, still, it was a very self-conscious gesture.

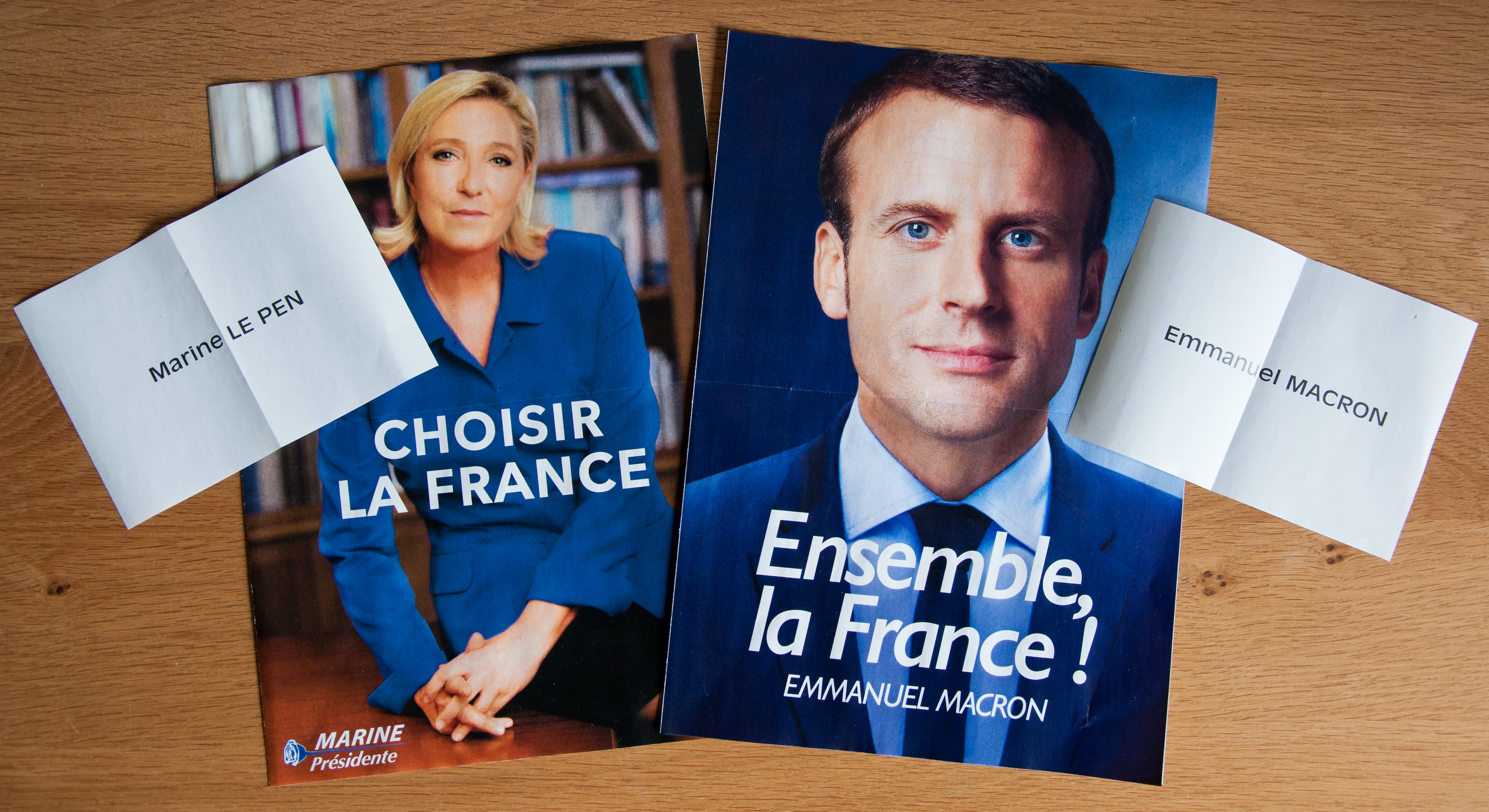

Macron and Marine Le Pen

Photo by Guillaume Destombes

The year 2020 is an anniversary year: de Gaulle was born in 1890, he made his broadcast in 1940 and he died in 1970. Macron, who has made many references to de Gaulle in 2020, went to celebrate a really very minor event in de Gaulle’s life: a skirmish on 17 May 1940 at Montcornet, when de Gaulle is still a soldier and before he becomes a political figure. It was a skirmish in which de Gaulle and his tanks acquitted themselves relatively well in a pretty disastrous moment for the French armies, but it’s not something most people have made very much of. Yet, Macron actually went to Montcornet and made a speech about this.

That shows one person putting themselves in the de Gaulle lineage. The other is Marine Le Pen. Marine Le Pen comes from a very anti-Gaullist family. Her father was an extreme right-wing politician, very nostalgic, it must be said, for Vichy and for Pétain. He was very much a supporter of French Algeria and therefore could not forgive de Gaulle for the betrayal, as he saw it, of Algeria in 1962; that’s to say, the independence of Algeria. Nonetheless, on 17 June 2020, the day before that famous anniversary, Marine Le Pen went to a little island off the coast of Brittany, the Île de Sein, from where about 100 fishermen left in June 1940 to join de Gaulle in London. Marine Le Pen went there to say: ‘I, too, despite my political family’s hatred of de Gaulle, am putting myself in the tradition of de Gaulle, and I am showing respect for him’.

Nostalgia for greatness

The myth today is not primarily about what de Gaulle did or who he was, though it’s obviously not disconnected from that. I think in that myth, there’s a certain nostalgia for the last moment when France really counted in the world – intellectually, culturally and, to some extent, economically. De Gaulle was president of France from 1958 to 1969 – and those were actually very great days.

The most famous intellectual in the world was Jean-Paul Sartre. The most famous actress in the world was probably Brigitte Bardot. The Caravelle, the Concorde, the Citroën DS were all emblems of a country that was confident, that was expanding, that was proud of itself. The nostalgia for de Gaulle today is partly a nostalgia for a moment of, to use a Gaullist word, greatness. One of his key words is grandeur. When the French heroise de Gaulle, they’re displaying a certain involuntary nostalgia for the last moment before the crises of the 1970s when they could feel proud of themselves.

A certain idea of France

One of the key phrases that everybody associates with de Gaulle is that which opens his war memoirs: a certain idea of France. The book I wrote on de Gaulle is called ‘A Certain Idea of France’ because it seems to be the phrase that sums him up. What does it mean? In that first paragraph of his war memoirs, he makes a curious distinction between France, for which he has an almost mystical reverence, and the French. He talks about France like a Madonna in a fresco, a princess of a fairy tale. He has a very emotional, mystical link with this idea of France, but he then goes on to say ‘...and if, however, France turns out not to be worthy of the image that I have of her, the fault is ascribed to the French.’

So, he makes this curious distinction between the French, who are not always worthy of this wonderful France: they’re quarrelsome, they’re divided, and so on. That’s something that he sets up at the very beginning of his war memoirs, and it comes back throughout his life. He famously used to make slightly dismissive comments in private. He said the French are like cattle: Les français sont des veaux. They’re weak, they’re divided. He wouldn’t have said that in public, and he didn’t really mean it, but he does make this kind of distinction between an idea of what the country should be and the reality.

What de Gaulle thought France should be

Photo by Benny Marty

My own view is that this idea of France was actually never fixed. We mustn’t become obsessed with de Gaulle having a simple single idea of what his country should be. If it doesn’t sound too pretentious, I would say that de Gaulle was, what I would call, an existentialist nationalist, and not an essentialist nationalist. I’ll explain what I mean by that.

He was not a nationalist who believed that France had to remain in a kind of aspic – that France is this, and it is fixed once and for all. On the contrary, he was obsessed with movement, the need for change, the need for adaptability. That’s what I mean by existentialist nationalist. He was a nationalist who was always restlessly thinking that France, to exist, must always change, must always develop, must modernise.

Discover more about

The Myth of de Gaulle

Jackson, J. (2019). A Certain Idea of France: The Life of Charles de Gaulle. Penguin.

Berstein, S., Birnbaum, P., Rioux, J., et al. (2008). De l'appel de Londres au discours de Chaillot, 1940-1944. in Serge Berstein (ed.), De Gaulle et les élites (pp. 35-46). Paris: La Découverte.