In the early days, the labour force comes from indentured white people, prisoners of war and people disaffected politically from the shifts going on in British politics – and some enslaved Africans. However, it soon becomes clear that Africans – from the planters’ point of view – are the most able to deal with the extraordinary levels of mortality in the Caribbean.

The history of slavery in the British Empire

Emerita Professor of History

- From the late 17th century onwards, England’s insatiable appetite for sugar drove the plantation economy.

- Slave owners controlled all aspects of their captives’ lives, and the separation between mother and child was common practice.

- Far from ending with the abolition of slavery, patterns of racialisation have endured to this day.

Slavery in the Caribbean

Photo by Bakhur Nick

The sugar factor

By the middle of the 17th century, the idea of a sugar economy based on enslaved labour on plantations develops, and this is connected to the increasing importance of sugar in the Western market.

Sugar is shifting slowly but surely from a fantastic luxury available only to the wealthy to something much more in demand. For example, in the late 17th century, you get the development of coffee shops in urban centres in England, which, of course, sell tropical produce: coffee and cocoa with sugar. By the early 18th century, it’s become an extraordinary site of wealth, with great enthusiasm from merchants for being involved in this West India trade, which was seen as an extraordinary source of profit.

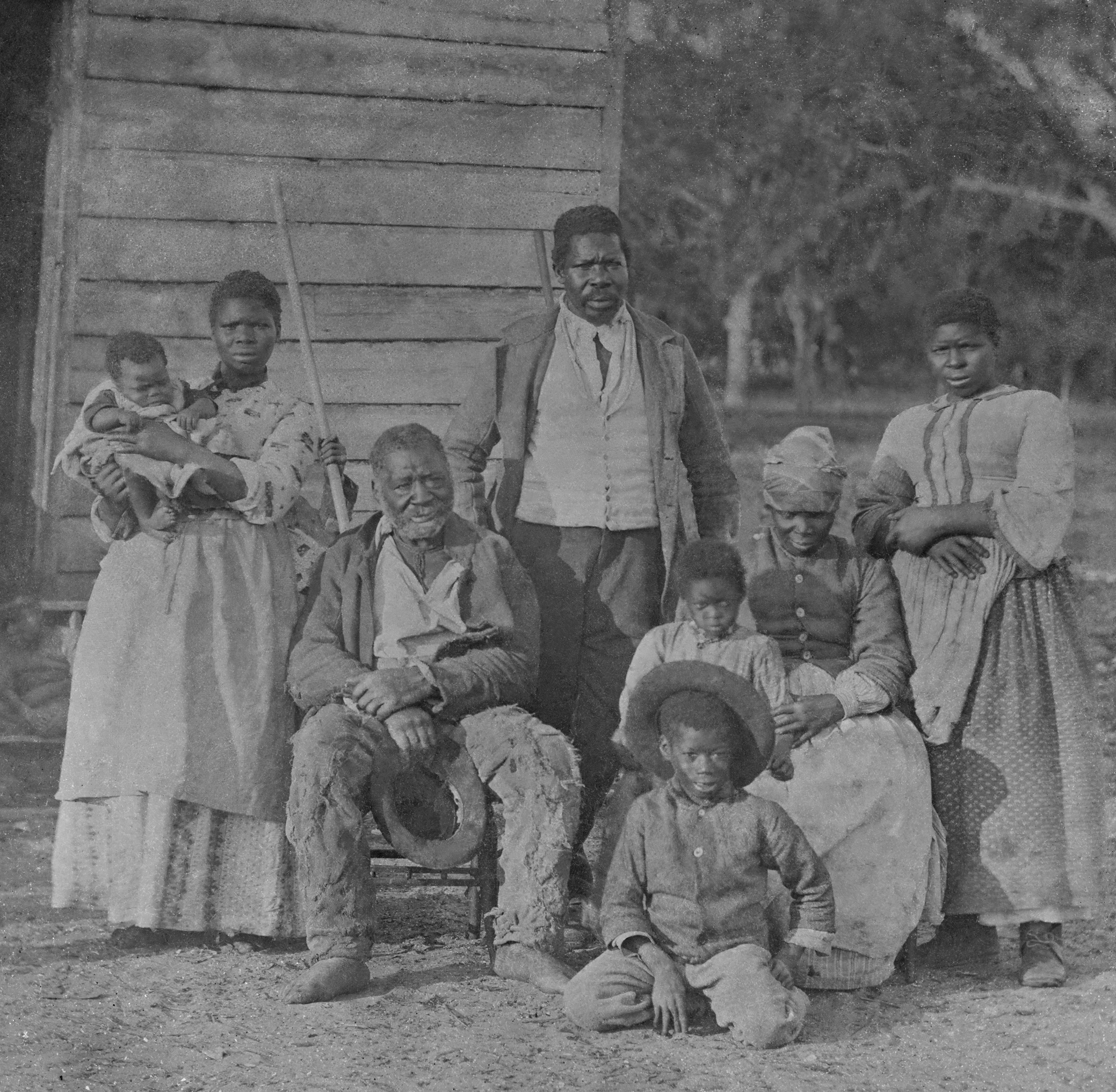

Family separation

One of the most important things that happened in the 1660s was that in the colony of Virginia, they made the decision that the babies of enslaved women were owned by the slave owner. The mother did not own her own child. This made slavery heritable, which was a complete break from the pattern of inheritance in England, where it passed through the father, not through the mother. This was a distinctive new law associated with slavery that was first introduced in Virginia: that the ownership of the mother’s womb was not her own.

It’s the most terrible thing, when you think about it. It’s shocking. This code of the heritability of slavery was taken up in Barbados and in Jamaica in the 1660s. So, in a way, this was one of the most important aspects of the treatment of captives. We usually think of the cruelty of slavery being associated with capture – which, of course, it is – with violence, with the whip. But there’s another kind of violence, which is the violence of the separation between mother and child and the refusal of the bond between mother and child. That’s a very important aspect of the gendering of slavery that hasn’t been given sufficient attention.

Blackness means slavery

Photo by Everett Collection

The new slave codes of the 1660s set the patterns of racialisation. Freedom was associated with white people who are described, for example, in the Jamaican slave codes with a capital W. Servitude was associated with enslaved Africans described as Negroes with a capital N. They don’t really use the term slave, so the link is immediately made between the blackness of the skin and the state of unfreedom. White men could own property; could vote, if they had a certain amount of property, for the new elected assemblies that were set up; had a code of law which drew on English common law. Enslaved Africans, now named Negroes, had a different code. In effect, their owner had almost complete control over the bodies and lives of those he owned, with the back-up of the colonial State when it was required.

Slave owners knew perfectly well that their captives were human beings. Yet, they denied that humanity in many respects, because, of course, they relied on the humanity of their labourers to function as human beings; as people who could do the work that they were coerced into doing; who lived lives, who bore children, who needed food; all the human aspects of life, as they were understood. That’s the fundamental pattern of racialisation that is set in slavery, and slavery was one of the first arenas in which these relations were codified in that way, so that whiteness means freedom and blackness means slavery.

One cruel system among many

Slavery is not the only form of racialisation across the British Empire. There are many, many others. The period of the colonisation of Ireland, which precedes what goes on in the Caribbean, is one of the arenas in which new ideas about differences – in this case between white people – were established. Those of Irish heritage were seen as inferior to those of English heritage. Still, within the hierarchy of belonging, the Irish came above Negroes. Similarly, in British India, Indians were also racialised, but their forms of racialisation were different. So, one of the things that’s really important to recognise about slavery is that it’s one system of violence, coercion and destruction across the British Empire – but it’s by no means the only one.

Slavery called into question

Photo by Adam Gilchrist

The patterns I’ve been describing of racialisation in the Caribbean, particularly associated with the plantation economy, were taken back to the so-called mother country by colonists, most of whom never intended to stay in the Caribbean. What they wanted was to make a fortune in the Caribbean, which some of them very successfully did. Others went broke. Many died because of the levels of mortality, both Black people and white people. The Caribbean was a place of death in the 18th century for so many.

Those who succeeded and managed to get out came back to England and to Scotland, which is where the majority of colonists came from, and they brought back with them these patterns of racialisation. They often brought enslaved people with them so that, as we’ve discovered more and more, there were far more Black people in Britain in the early modern period than used to be thought the case. However, they also brought the ideas, so that along with the enthusiasm for Empire, which was certainly very widespread in the early 18th century, there began to be questions about whether slavery was really such a good thing. It certainly brought wealth and power, but what about the moral questions and moral difficulties associated with that? Was it right to own other people? And so the debate becomes one in the metropole about the morality and the legitimacy of slavery. That surfaced in the 1770s and then builds up to be the 1807 campaign for the abolition of the slave trade and, eventually, for the abolition of slavery in 1833–1834.

Enduring patterns of racialisation

The abolition of slavery in no way meant the ending of ideas about race. Far from it. Once slavery wasn’t there to legitimate why Black people should labour for white people, new kinds of legitimation were found. Patterns of racialisation became deeply embedded in British culture and across the Empire in the 19th century. Different understandings of peoples and their capacities, far from ending with abolition, became embedded in so-called “scientific racism” about the levels of intelligence and ability of different groups of people. As in the 20th century, those ideas have been increasingly challenged, but although it is widely recognised now that there is no scientific basis for racial difference, of course, racisms have never ended. The ways in which racialisation has been structured into contemporary societies remains a major problem in the contemporary world.

Discover more about

Slavery and the British Empire

Hall, C. (2002). Civilising Subjects: Metropole and Colony in the English Imagination, 1830–1867. University of Chicago Press.

Hall, C., & McClelland, K. (Eds.). (2010). Race, nation and empire: Making histories, 1750 to the present. Manchester University Press.

Hall, C., & Rose, S. O. (Eds.). (2006). At Home with the Empire: Metropolitan Culture and the Imperial World. Cambridge University Press.