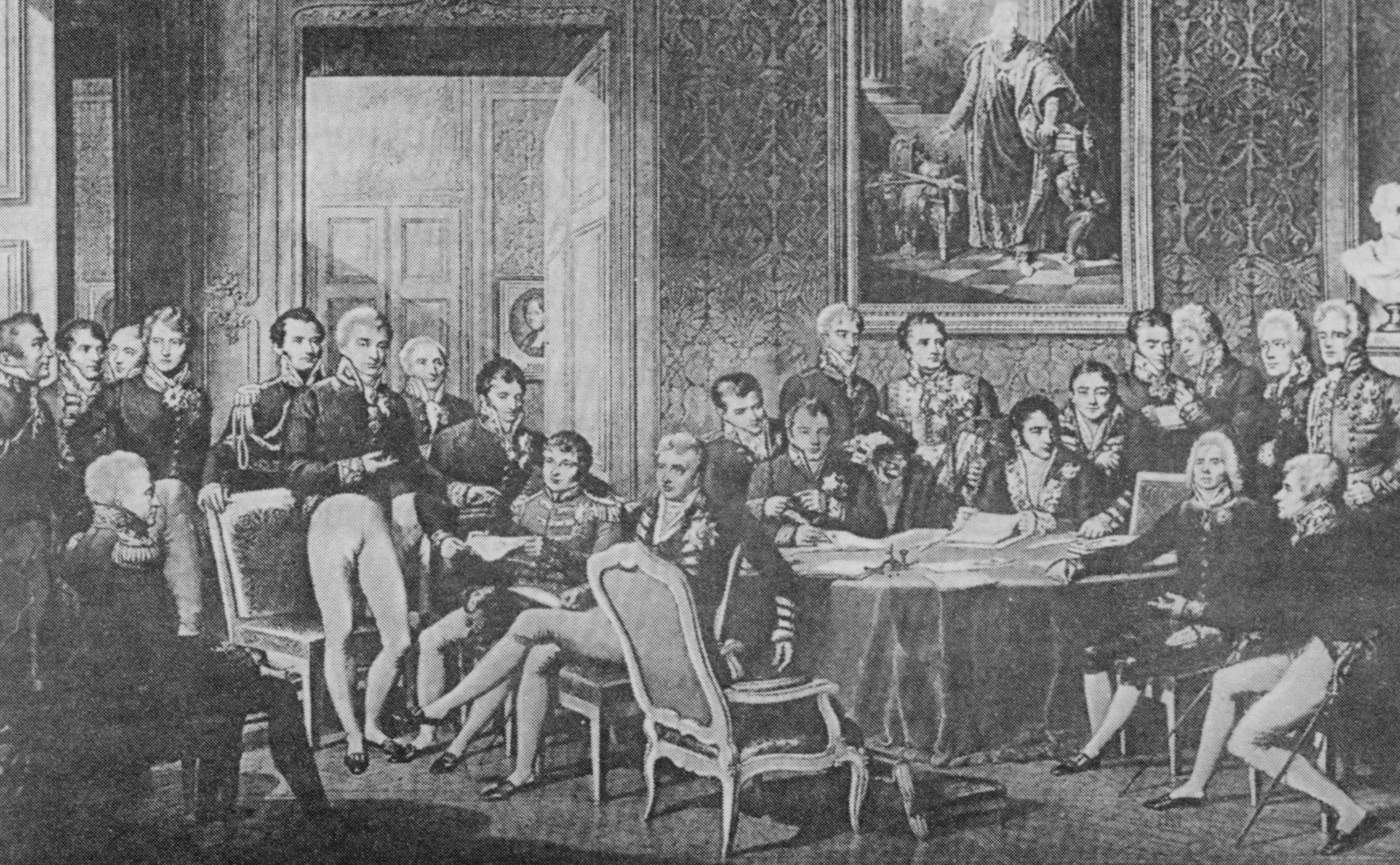

One question we can ask is what idea of Europe we have coming out of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. Napoleon is a complicated and a controversial figure. From one point of view, he represents French militarism. This is a familiar story in histories of European nationalism: the nations of Europe come together to resist French military domination, there’s a German national uprising in 1813, and this is the staple of the old historiography. Napoleon is figured as a universal monarch. The powers that resist Napoleon have a vision of a Europe in which they cooperate with one another to keep the peace and respect the independence of the different countries.

From another point of view, Napoleon represents bureaucracy, uniform administration and modernisation. Napoleon was a French ruler, but wherever he went, he imposed law codes; he reformed the law. He worked to break down the structures of the old European aristocracies, the remnants of European feudalism. So, from this point of view, Napoleon’s activity lays the foundations for a form of European union.