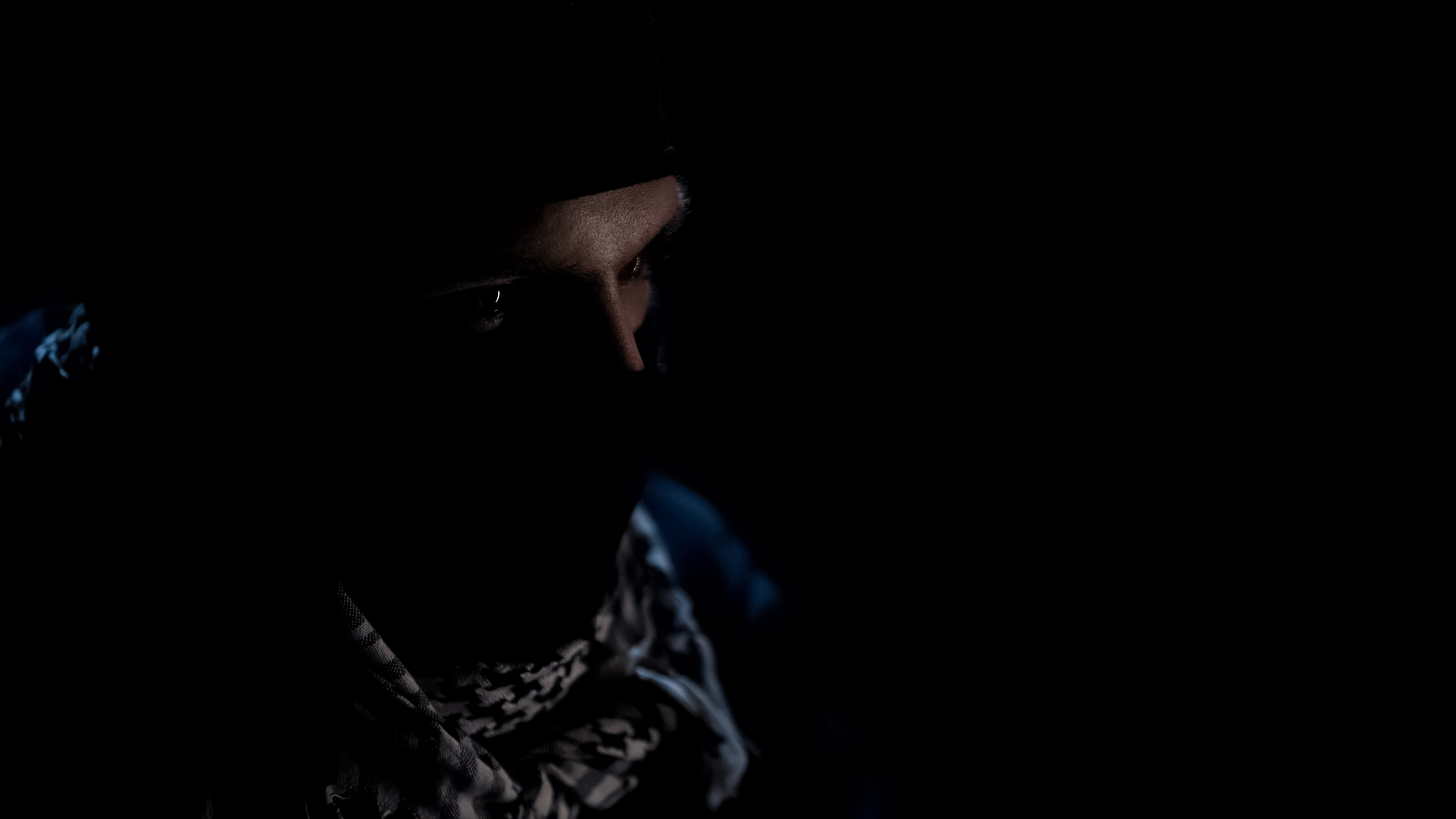

I remember a long conversation I had with Abu Qatada, who was the European leader of Al Qaeda. Initially, I assumed that the religious dimension of the violence was as essential to him as it is to me. However, as I explored the topic with him, he stopped me and said, ‘Well, I’m perfectly happy for us to talk about our religious agreements and disagreements, but the reason for the violence is not to do with that. It’s a political problem. It’s a problem of external forces controlling our part of the world, and we can’t find any other way to get rid of them.’ That was a fascinating perspective, and our conversation took a different turn from what I had expected.

There was a rational element to all of that, but we can think of all sorts of things one would consider rational. We could have a conversation about what to change in the world, but it doesn’t necessarily mean we want to go and sacrifice our lives doing it. Doing so requires something else, something compelling, in terms of our feelings. We need to have powerful emotional drivers and cognitive drivers to behave in such a drastic manner.